René Slotkin, one of the few surviving ‘Mengele twins,’ dies at 84

Slotkin and his sister were among just 200 sets of twins to survive gruesome experimentation by the infamous Nazi physician Josef Mengele at Auschwitz

René Slotkin, photographed here by B.A. Van Sise, died July 10 at the age of 84. (Image courtesy of B.A. Van Sise / Design by Mollie Suss)

(JTA) — As a physical education teacher at an Orthodox boys school in New York City, René Slotkin frequently wore short-sleeved shirts — leaving the numbers tattooed into his arm visible to anyone who saw him.

His story of Holocaust survival was remarkable: Slotkin and his sister were among just 200 sets of twins to survive gruesome experimentation by the infamous Nazi physician Josef Mengele at Auschwitz, then were reunited six years after being separated.

Slotkin’s story, which he told and retold, including in a film about his family, was never far from the minds of his fellow congregants at Congregation Ohab Zedek, the Upper West Side synagogue down the block from his home where he studied Talmud every morning well into his 80s.

“I still find it staggering that a man who saw so much horror and devastation not only clung to his faith and belief, but did so with happiness and hakarat hatov,” or gratitude, Jonathan Field wrote in the Jewish Link on Friday about his fellow congregant, who died on Sunday at 84.

Born René Guttmann in 1937 in Teplice-Sanov, Czechoslovakia, René was only 4 years old when he and his twin sister Irene were deported to Theresienstadt with their mother, Ita, in 1942. (Their father Herbert was taken to Auschwitz in 1941 and died there.) Two years later, they were moved to Auschwitz, where their mother was killed and the twins were separated and subjected to medical abuse by the infamous Nazi physician Josef Mengele.

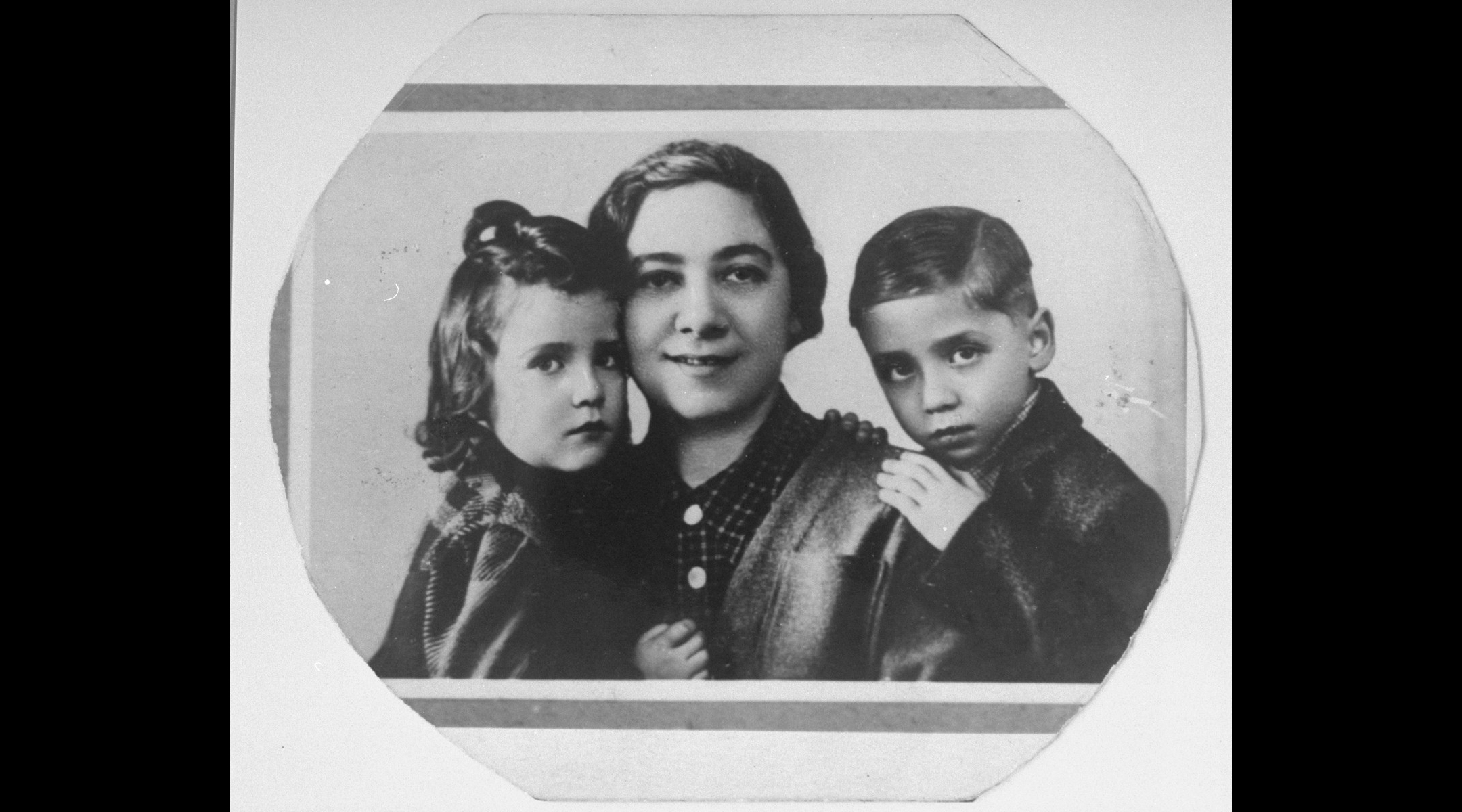

Ita Guttmann and her twins, Rene and Irene (then Renate) were photographed for Nazi propaganda while they were imprisoned at Theresienstadt. (Courtesy of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum via Irene Guttmann Slotkin Hizme.)

After the camps were liberated, René was repatriated to Czechoslovakia and lived with two families. Irene, who had initially been placed with a Christian family in Oświęcim, Poland (the town where Auschwitz is located) was eventually found by the Joint Distribution Committee, who wanted to return her to a Jewish family. Irene and another survivor became the “poster children” for the Rescue Children Inc. initiative and were taken to New York City, where they were photographed for LIFE Magazine. Shortly thereafter, Irene was adopted by the Slotkin family in Long Island.

After Irene told her adoptive parents that she had a twin brother, the Slotkins hired a private investigator to look for him in Europe. In a rare story of reunification, René was adopted by the Slotkins in 1950.

He was 12 and had not seen his sister in six years — half of their life.

In “René and I,” the 2005 documentary about Irene’s life, Slotkin recalled that moment of reunification.

“As a matter of fact, the night that I arrived in America and we first saw each other, we said nothing. We just looked at each other,” he said. “There was no running to each other, hugging or kissing. Nothing like that. That was it. That’s all I remember from that night.”

After college, Slotkin joined the National Guard, where he reached the rank of sergeant and served in the reserves for seven years. He was one of the few survivors of Auschwitz who served in the U.S. military, and he was also unusual for wearing a kippah and observing Shabbat during his service.

He remembered being shocked that his fellow military members did not know much, if anything, about Judaism, and that they didn’t recognize the numbers on his arm as that of a concentration camp tattoo — they had assumed it was a Social Security number or a phone number.

René’s first son was born while he was in the military, and he and his first wife had two more children before they divorced. Some years later, he married a teacher, June Slotkin, with whom he had a daughter.

It took Slotkin and his sister nearly four decades before they started speaking openly about their experiences during the Holocaust. In 1985, they went to Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial, in Jerusalem to take part in a mock trial of Josef Mengele focused on his abuse of twins, where Nazi war crimes investigator Simon Wiesenthal served on the panel. Mengele’s body was discovered in Brazil a year later. He had drowned in 1979.

In his later years, Slotkin volunteered at Camp Sharon in Tannersville, New York, where he taught woodworking and sports, and taught children about the Holocaust and what it means to be a survivor.

Throughout his life, René Slotkin enjoyed working with children, teaching them sports and woodworking and educating them about the Holocaust, which was captured in the 2005 documentary, “René and I”. (YouTube)

“I want kids to know how I appreciate life today,” he said in “René and I.” “I tell them the things that I’ve learned and the things that I consider of value are things that should be passed on.”

In the 1990s, Irene developed multiple sclerosis, which she and her brother attributed to the abuse she suffered as a Mengele twin — they suspected that she was the one subjected to “experiments” while René was the “control variable.”

Irene died in 2019.

“I feel very, very lucky that I escaped,” Slotkin said in the 1997 interview. “I have what I think are the true riches. I have a wife that loves me, that I love. I have a family. I belong to a synagogue, I’m a member of a community. I have good friends, I seem to be healthy.”

He added: “But then there’s a little bit of emptiness.”

René is survived by his wife June, whom he called “the best woman in the world”; his four children, Zebbe, David, Corrie and Mia; 11 grandchildren, and a great-grandchild. The funeral service was held at Congregation Ohab Zedek on Sunday.

In recounting his story to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Slotkin said, “Perhaps these comments, perhaps the tapes that I’ve done, perhaps the shows that we’ve recorded, perhaps in the future, maybe that is the thing that’s going to count and serve.”

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.