Spotted in a Nazi’s daughter’s real estate ad: a painting looted from a famed Jewish art dealer

The painting was owned by Jacques Goudstikker, who died while fleeing the Nazis in 1940

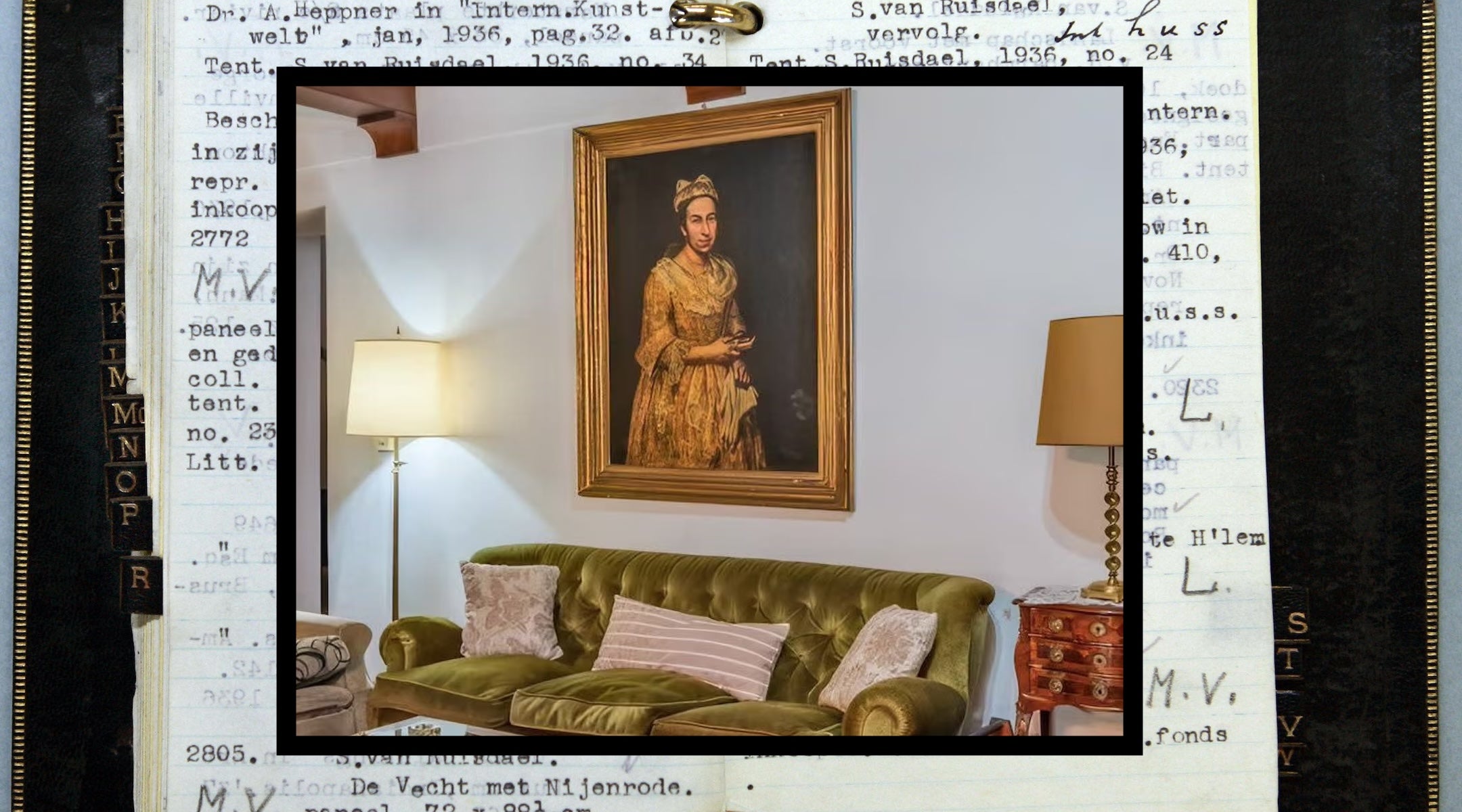

The Dutch Jewish art dealer Jacques Goudstikker kept a record of his holdings in a pocket notebook in the 1930s. Among the paintings he owned when he died was one that has reappeared in a real estate ad in August 2025 in Buenos Aires. Photo by Black book by Marcel Antonisse/AFP via Getty Images; real estate photograph from Robles Casas Campas

(JTA) — An investigation by Dutch journalists has led tantalizingly close to the recovery of a painting looted from a Jewish art dealer 85 years ago.

But no sooner was the work by the Italian painter Giuseppe Ghislandi glimpsed in a real estate ad for a luxury property in Argentina than it promptly disappeared.

Now, Interpol and Argentine police have joined the search, urgently trying to prevent “Portrait of a Lady” from disappearing once again, perhaps for good.

Their search is focusing on the seller of the luxury property: the daughter of a high-ranking Nazi who took refuge in Argentina after Germany lost World War II. Friedrich Kadgien, a close advisor to Reichsmarschall Herman Göring, died in Buenos Aires in 1978, and his two daughters still live there.

The discovery has injected a jolt of drama into the field of looted-art restitution, which has slowed over time and more often is occupied by slow-moving legal battles over ownership.

“Portrait of a Lady” was one of nearly 1,000 works bought in a forced sale in 1940 by prominent Nazis — including Göring — after the untimely death of their owner, the prominent Jewish collector Jacques Goudstikker.

Goudstikker died at sea in an accident while fleeing the Netherlands with his family, who ultimately settled in the United States. The collector, who reportedly helped other Jews escape during the war, is buried in England.

After the war, parts of his collection — which he recorded in a black book he was carrying when he died — were found and displayed in Amsterdam’s Rijkmuseum. In 2006, after a decade-long battle that overlapped with the establishment of international principles around the restitution of looted art, more than 200 works were restituted to Goudstikker’s only surviving heir, his daughter-in-law Marei von Saher, now 81. It was one of the largest acts of restitution since the Holocaust, and a major exhibition of the works was staged at the Jewish Museum in New York. Many of the pieces have since been sold to private collectors.

But the Ghislandi portrait, of Contessa Colleoni, was not in the trove. Painted in the early 18th century, it remains on more than one list of Nazi looted art, including that of the Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency.

A reporter at the Dutch newspaper Algemeen Dagblad, Cyril Rosman, began searching for the painting some 10 years ago, after receiving a tip from retiree Paul Post of Driehuis in North Holland. Post’s father had worked at the National Diamond Bureau in Amsterdam during the war. The occupying Nazis had extorted Jewish diamond traders, falsely saying they could avoid deportation by handing over their gems.

Post, who had discovered his father’s diary in his attic, kept at the story, tracing how looted diamonds were used to support the German war industry. A key figure in this scheme was Kadgien, whom Post learned had fled Germany with some diamonds and two paintings — one of them the portrait by Ghislandi.

Rosman tried in vain for years to speak with Kadgien’s two daughters, whom he did not name.

A break in the investigation came when one daughter put the family home in the coastal town of Mar del Plata up for sale.

On Monday, Rosman reported that the painting was seen in a photo on the website of the Robles Casas & Campos real estate company, hanging above a green sofa.

Art historians Annelies Kool and Perry Schrier with the Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency said it looked like the real thing. “Recovering a painting like this is rare,” they told the paper.

The reporters also spotted another artwork reported as looted, this one by 17th-century Dutch painter Abraham Mignon, on one of Kadgien’s daughters’ social media posts going several years back.

Occasionally works are squirreled away in private hands and only come to light by chance. In 2013, a trove of Nazi-looted art was discovered in Munich after collector Cornelius Gurlitt was investigated for tax evasion.

Deidre Berger, chair of the executive board of the Jewish Digital Cultural Recovery Project Foundation, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency that an estimated 600,000 Nazi-looted artworks remain missing, whether in public and private hands.

More could be uncovered “if governments worldwide would digitize and transcribe their relevant archival holdings,” she said. But in the current case, the rediscovery was a matter of luck and hard work by journalists and the Cultural Heritage Agency.

After the painting was spotted, Algemeen Dagblad reporter Peter Schouten in Argentina contacted one of the daughters by phone. She told him to send his questions by email: “I don’t know what information you want from me, and I don’t know which painting you’re talking about,” she said.

After receiving the questions and a photo of the painting via WhatsApp, she responded that she was “too busy to answer right now.” And then, silence.

The real estate ad was pulled from the site. According to the newspaper, the daughter reportedly has also changed her name on Instagram.

Contacted by the paper after the discovery, heir Marei von Saher said it was her “family’s goal to recover every artwork stolen from the Goudstikker collection.”

Today, she has the Argentine Federal Police and Interpol on her side.