Robert Jay Lifton, pioneering scholar of Nazi doctors and Jewish memory, dies at 98

His 1986 book, “The Nazi Doctors,” explored how healers became killers

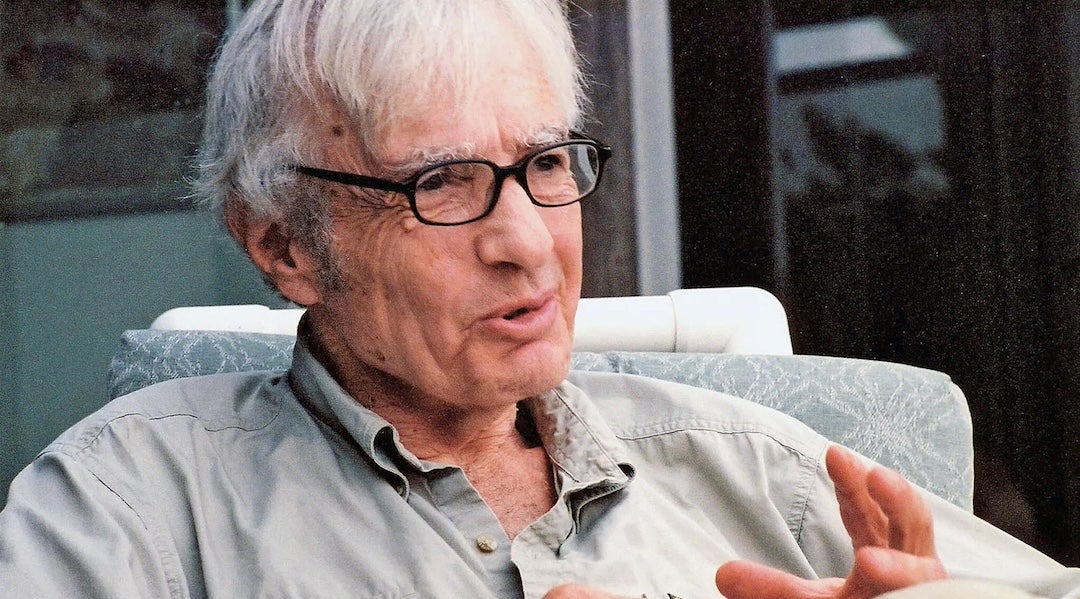

Robert Jay Lifton in a 2009 documentary based on his book, “The Nazi Doctors.” Photo by Wolfgang Richter/National Center for Jewish Film

(JTA) —

Robert Jay Lifton, the psychiatrist and public intellectual whose groundbreaking work on the psychology of genocide shaped Holocaust and Jewish studies for the past 40 years, died on Thursday at his home in Truro, Massachusetts. He was 99.

Lifton, who was raised in Brooklyn, the son of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, devoted his career to exploring the human capacity for both cruelty and resilience. His 1986 book “The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide,” documented how physicians were enlisted in the machinery of the Holocaust.

Lifton spent a decade interviewing Nazi doctors and concentration camp survivors to piece together the motivations of physicians who carried out horrendous medical experiments and assisted in the extermination of Jews and others under the Nazis.

Although not without its critics, some of whom were dubious that psychiatry could be applied to mass phenomena, the study deepened historical understanding of the Holocaust and became a touchstone for bioethics and the study of evil.

In a 2009 documentary, “Robert Jay Lifton: Nazi Doctors,” Lifton wrote that he was fascinated by the “reversal of healing and killing.”

“If a whole society including the professionals, the doctors in particular, can be socialized to killing,” he says in the film, “it makes genocide much easier to carry out.”

Throughout his career, Lifton’s writings bridged psychiatry, history and Jewish thought. He investigated how survivors of Hiroshima, Vietnam veterans and Holocaust survivors alike wrestled with trauma and memory. His concept of “survivor guilt” and his exploration of “the protean self” influenced generations of scholars across disciplines.

In Jewish studies circles, Lifton was admired for insisting that Holocaust scholarship must remain central to understanding Jewish identity in the modern era. He lectured widely at Jewish institutions, advised Holocaust memorial projects, and inspired students to see Holocaust memory as both a scholarly field and a communal responsibility.

Lifton remained engaged with current events well into his 90s, and was a vociferous critic of Donald Trump, whom he described as an exemplar of how “a rush of falsehoods may inundate an entire society.”

In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic and amid increasing anxiety over climate change, Lifton drew on his lessons about trauma and its aftermath to write “Surviving Our Catastrophes: Resilience and Renewal From Hiroshima to the Covid-19 Pandemic” (2023).

“Meaning depends upon memory,” he wrote, describing the risks when societies do not grapple with the lessons of the past and their own missteps.

“That failure to retain such crucial historical knowledge left us psychologically vulnerable to Covid-19, which we perceived as totally unpredicted and random, having no relationship to anything before it,” he continued.

Lifton taught at Yale, Harvard and the City University of New York, and his many books reached audiences well beyond academia. His work was honored with numerous awards, including the National Book Award in Science for “Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima.” In 1987, he won the National Jewish Book Award in the Holocaust category for “The Nazi Doctors.”

He is survived by his daughter, Natasha Lifton; his son, Kenneth Lifton; his partner, Nancy Rosenblum; and four grandchildren. His wife, Betty Jean Lifton, an author whose books included a trilogy calling for adoption reform and “The King of Children,” a biography of Holocaust rescuer and victim Janusz Korczak, died at 84 in 2010.