Facing a Changed World, on a Full Stomach

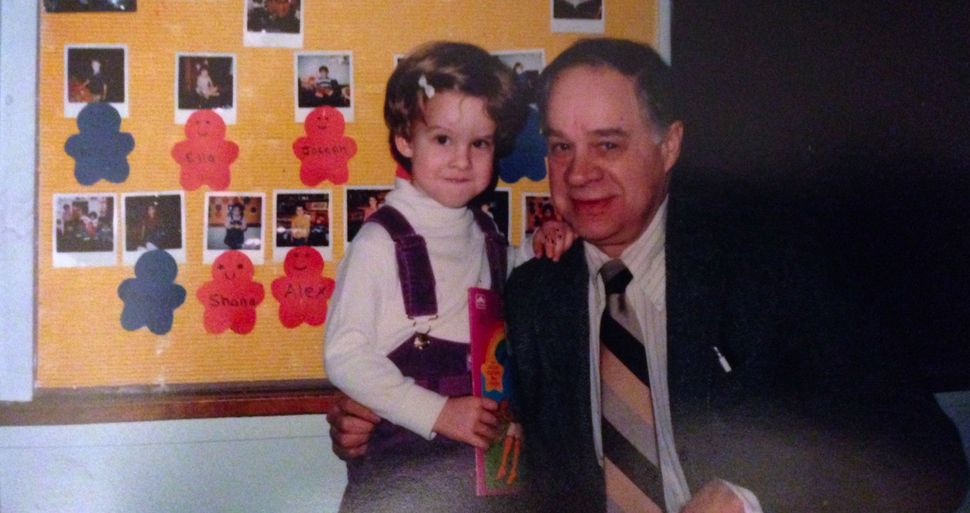

Image by Courtesy of Leah Koenig

Writer Leah Koenig (left) as a preschooler, with her father, Richard Koenig.

Something strange happened the day after my father died. I woke up the next morning hungry for breakfast. Everything else has shifted. The shape of my family tree had changed. Nearly everyone I loved was sad all at once. I realized that I could no longer begin the phrase “my dad…” while speaking in the present tense. But there I was at 8 a.m. with a stomach growling, as it does every day, for cereal.

My father, Richard Koenig, passed away last month on the day before Thanksgiving. Having recently celebrated his 92nd birthday, it was not unexpected. (At 33, I am the second child of his second marriage, but the youngest of six in all). He was emotionally ready to go — to his mind, the whole thing was actually quite overdue. He had the chance to say goodbye to all of his children and loved ones, many of us in person. And he went the way everyone says they would like to: peacefully and quickly in his sleep.

When my mother called to tell me that Dad was gone, it felt strangely natural. With such an older father, I had started grieving this moment years before. Now that it arrived, it felt just like that. Like, “Okay, here we are.” “Okay, yes, this. I recognize you.”

Now nearly two weeks on, I find myself struggling to know quite how to feel. Dad made an end-of-life decision to donate his body to science, which meant no immediate funeral. And since he wasn’t Jewish, sitting for a week’s worth of shiva did not feel like the right fit. Left without Jewish tradition’s comforting mourning rituals I felt, and continue to feel, adrift — sad, but not distraught. I’m filled with gratitude for the outpouring of love and support offered by friends, but not sure where to put it all. I’m waiting for the flood of emotion that people talk about when a parent dies, and feeling confused and guilty that it has yet to arrive.

In the weeks leading up to his death, my dad stopped eating almost entirely. Growing up, breakfast had been his power meal. The man thrived on routine, and during most of my lifetime he followed an unwavering breakfast regimen: black coffee, orange juice and an English muffin — split, toasted, topped with butter and strawberry jam, then sandwiched back together. He ate his morning meal with a napkin tucked into his collar to stop the dribbles of jam from landing on his suit and tie.

At the assisted living facility where he lived his last days, the trays of oatmeal, stewed prunes and cheese omelets delivered to his room went untouched. He said he didn’t have an appetite, but I think there was also an element of hunger strike there too. On my last visit in October, I urged him — like everyone was doing — to eat something. Or at least drink. How about some orange juice? Each time, he shook his head no.

In the moment, I was frustrated by this stubbornness. How could you not want breakfast? But now I understand: He simply did not see the point. Eating breakfast is what you do to acknowledge and prepare for the new day. But after a lifetime of breakfasts and new days, my father had eaten his fill.

Leah Koenig is the author of She is a contributing editor at the Forward.