Tea, cake and passionate political discussions

For years, the author’s parents hosted lively gatherings of Holocaust survivors in their home in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

I’m proud to have grown up in Bensonhurst in South Brooklyn in the 1950s and 1960s.

Bensonhurst was the home of “The Three Stooges.” Sam Gambino, the don of the nation’s largest Mafia family lived two blocks from my family. “Welcome Back, Kotter” character Vinnie Barbarino (played by John Travolta) was from Bensonhurst. The disco that was featured in “Saturday Night Fever” was actually a kosher catering hall above a Ford Dealership (“The Benson Chateau”) and was the venue for my 1963 bar mitzvah. Tony Soprano, like me, grew up in Bensonhurst. The climactic chase scene of “The Taking of Pelham 123” occurred down the block from the Benson Chateau. I purchased my shirts and ties at the haberdasher where Tony Manero (also played by Travolta) of “Saturday Night Fever” bought his disco shirts. Tony Soprano was said to have grown up in Bensonhurst.

But I believe the most important — and most enduring — feature of Bensonhurst was the Yiddish salon my parents hosted every week for fellow Holocaust survivors like themselves.

In Europe, and particularly in Paris, salons were gatherings in private homes where men and women of similar class, interests and outlook came together to discuss literature, politics, philosophy or current events. My parents’ salon, though, had a distinctly Jewish flavor.

My mother and father, who were both born in the tiny shtetl of Piltz (Pilicia in Polish), were married after liberation and arrived in the United States in 1950. I came onto the scene four months later.

We first lived in a small town in Western Pennsylvania; then moved to Chicago, where my sister was born, and then ultimately settled in Bensonhurst in November 1956. Since both my grandfathers were bakers (they had been competitors in Piltz), my parents opened a kosher bakery which they called the Sinai Bake Shop. We lived above the store and our quarters were modest.

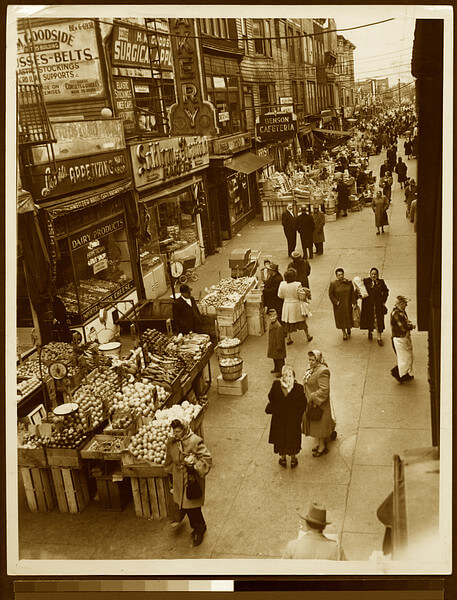

Bensonhurst then was primarily a mix of Italians and Jews. The Jewish community was largely comprised of survivors. As you strolled the streets, you heard people speaking either Yiddish or Italian. The Italian shopkeepers quickly learned the Yiddish words for the wares they purveyed. Mom would dispatch me to the fruit store to purchase zupn-grins (soup greens). When I asked how to say that in English, Mom said: “Zorg zikh nisht, Tony farshteyt.” (“Don’t worry; Tony understands.”) And he did. When I went to Vinny the fish monger and asked him for the ingredients for gefilte fish, he quickly provided them.

Following our arrival in Bensonhurst, other survivors, who were then first starting new lives in America, often found their way to our humble quarters and would spend weeks and sometimes months with us as they established new lives here.

My parents had a hardscrabble life. Dad baked bread products and supervised the baking crew that worked from 10:00 p.m. until 6:00 a.m. Then he drove our delivery wagon, supplying freshly baked goods to synagogues, catering halls, schools, restaurants, commission bakeries and small groceries, which our bakery serviced.

Mom was a saleslady and supervised the sales staff. She oversaw the books, paid the bills, scheduled the sales staff, dealt with vendors and tended to our home. She opened the store at 6:00 a.m. and closed it at 11:00 p.m. six days a week.

The busiest days in the bakery were Thursdays, Fridays and the two days before Jewish holidays. My parents worked until 15 or 20 minutes before the onset of shabbes and festivals. The bakery regimen required 60-hour work weeks from my parents.

Often, even as my parents were engaged in last-minute home preparations for a shabbes or yontef (Jewish holiday), a customer would knock on our apartment door, explaining that they were late in their own preparations and needed challahs and cakes for their families. Nobody was ever turned away or left empty-handed. At times, my parents even gave them baked goods that had been set aside for our family.

The highlight of the week was the shabbes or holiday afternoon. After a brief afternoon nap, Mom would set out a variety of cakes and pastries from their bakery, as well as fresh fruits on our dining room table. An industrial-sized urn, prepared on Friday, was at the ready for tea. My Dad would go to the corner candy store early shabbes morning and pick up copies of newspapers for which he had prepaid on Friday. The New York Times, The New York Post, Der Forverts, Der Algemeiner Journal and Der Tog Morgen Journal would all be neatly stacked on the table, next to the sweets.

Then they would start arriving in pairs – six, eight, 12 or more couples, all survivors. None were invited; they all knew that they would be welcomed. When we heard the creaking stairs that presaged their arrival, we greeted them before they even knocked. The guests would gather around the stack of newspapers, pulling out sections or even pages to read and pass around. As they scoured the papers, they often debated the issue of the day. The discussions were lively and always in Yiddish. Sharing wartime experiences were verboten because we kids were always around and they didn’t want to frighten us. Although most of us spoke English to our parents, we all had perfect Yiddish comprehension.

The guests would often dissect that week’s fiction column from the Forverts and debate its quality and the reputation and style of its author. They would opine on Israeli and domestic politics, and on issues argued at the U.N. They often discussed the quagmire of the Middle East. There were no discussions about new movies or television since most of them rarely watched either.

Sometimes, a guest would question the academic qualifications of another guest who had opined on some issue. The response was almost always: “Why can’t I offer my opinion? I have a Ph.D. with honors from the University of Bergen Belsen!” That always got a laugh. Even though none of them had gone to college and very few had attended high school, most of them were very erudite.

During my formative years, I would sit next to Dad during these sessions, as did several of my schoolmates. We could have gone to another room to play board games as we did every shabbos, but the truth is we were fascinated with these lively discussions and felt very grown-up just sitting there (except occasionally, when we excused ourselves and snuck into the bakery, eating gobs of chocolate icing with our hands).

Often, the discussions became loud and passionate, sometimes even angry. When that happened, Dad would tell a joke or anecdote that broke the tension. Dad’s collection of anecdotes and humorous stories was bottomless.

These gatherings lasted for hours. All partook of the refreshments and the bonhomie.

Say what you will about the fashionable salons of Paris, Venice, Vienna, Budapest or London, where assemblages of notables, literary figures, artists, or statesmen would gather at the home of a prominent person. None held a candle to the Yiddish salon over which my parents humbly presided. Their guests may have been just bakers, butchers, tailors, shopkeepers, tradesmen and blue-collar workers, but they were bright and well-informed and sincere about their beliefs.

But there was something else about them too. Unlike the children of our American neighbors, we kids of survivors had almost no aunts or uncles or first cousins. So for us, these men and women chatting, yelling and laughing on shabbes and yontef afternoons, were not just friends of our parents. They were family.