Groundbreaking album breathes new life into nearly abandoned Jewish musical art

Jeremiah Lockwood sought to revive the early 20th century style of cantorial music; he found unexpected partners in the Brooklyn Hasidic community.

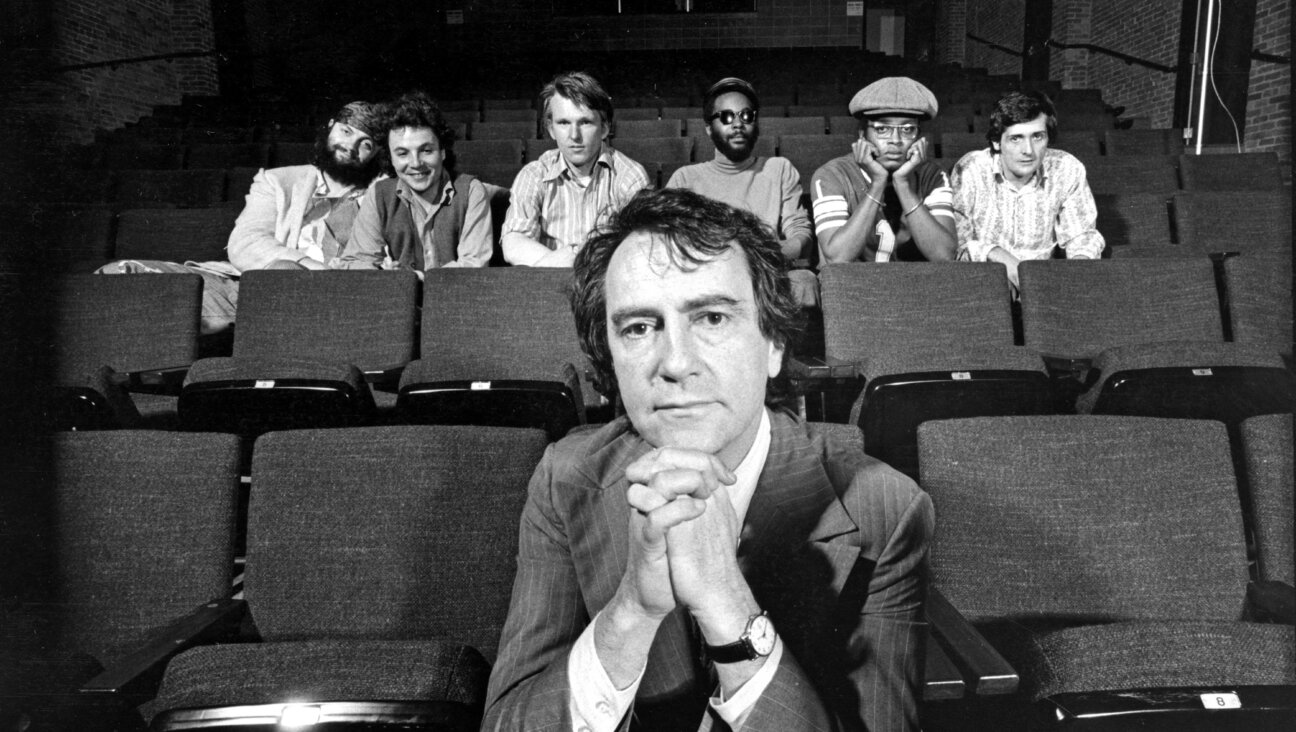

Yoel Kohn singing cantorial music on the album “Golden Ages: Brooklyn Chassidic Cantorial Revival Today” Photo by Tatiana McCabe

The most sought-after figures of Jewish life in early 20th century Europe and America were the khazonim, the cantors. They led services in synagogues and gave performances in concert halls, with wide operatic ranges and stirring pathos. Cantors like Gershon Sirota, Yossele Rosenblatt and Zawel Kwartin were paid top dollar. Rosenblatt was advertised on a tour across America as “the man with the $50,000 beard,” in reference to his traditional appearance and the princely sums he commanded. He even performed in the 1927 film “The Jazz Singer,” the world’s first “talkie,” where he took a cameo after passing up a leading role.

Yet, despite the similarity to classical operatic singers, the Eastern European-born cantors of the Golden Age (often defined as the period between the late 19th century and World War II) sang in ways foreign to conventional opera. A good portion of their singing was actually improvised.

Many of the terms used in the cantorial singing of this era have evocative Yiddish names. A great cantor would “zog” (say) the words of liturgy with complete humility, as though he were speaking to God directly. Most khazonim possessed multiple “voices,” completely different vocal ranges that they could turn to in the middle of a piece – or even in the middle of a phrase. They could switch from a booming voice that shook the room to a soft, plaintive “baykol” (falsetto), which took over at the most sensitive moments.

At any time, a pungent sadness could be punctuated by a “krekhts,” — an intentional sudden voice break that sounded like crying. “Dreydlekh” (trills) and other embellishments allowed the cantor to demonstrate amazing vocal control in coloratura — long phrases filled with lightning-fast ornamentation that could dazzle the listener. The emotional release of his music, sung humanely yet with great skill, often brought people to tears. No wonder that Jews and non-Jews alike would come from miles away to see these stars perform.

The cause of the style’s drop in popularity came from the same forces that assailed Yiddish: The murder of six million Jews in the Holocaust in Europe; the repression of Jewish culture in the Soviet Union and the distancing of American and Israeli Jews from the perceived weakness of the Jews of the Old World from which the style came.

But the fall in popularity didn’t happen all at once. First, the cantors in the 1950s became masters of the cantorial music as written, but no longer performed it with the passionate energy and improvisation of the shtetl prayer leaders that had inspired the Golden Age cantors.

In 1966 Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel gave a speech decrying this rote performance of once-improvisatory music. “The tragedy of the synagogue is in the depersonalization of prayer. Hazzanuth has become a skill, a technical performance, an impersonal affair. As a result the sounds that come out of the Hazzan evoke no participation. They enter the ears; they do not touch the hearts.”

Heschel wasn’t the first to complain about this. When cantors first began recording liturgical music on vinyl and singing it in theaters, it was denounced by some who claimed that prayer was becoming profane. (One critic bitterly protested that words of prayer were being listened to in brothels.) Yet, Heschel’s complaints weren’t really directed to the khazn – he spoke more against the Americanization of the synagogue at-large, changing it from a communal gathering spot with the casual warmth of the Old World, to a more stately but tepid affair, which the khazn had no choice but to adapt to. As Heschel lamented in that same speech: “Following a service, I overheard an elderly lady’s comment to her friend: ‘This was a charming service!’ I felt like crying. Is this what prayer means to us? God is grave; He is never charming.”

Over time, the nuances that made cantorial music emotionally impactful were dismissed as “old-fashioned,” and teachers of the Golden Age stylization became harder to find. Though musical pieces of that era are still performed around the world, the stylizations of those days were cast aside in favor of a purely operatic style. Its heymish Yiddish character was increasingly shunned in a society that wanted less and less to do with its own language and culture.

Around the 1970s, the synagogue experience was transformed by communal singing accompanied by guitar, spread by inspiring new folk singers like Debbie Friedman in the Reform movement, and Shlomo Carlebach in the Orthodox. Professional cantors who adapted to these new musical tastes could keep their jobs, but many who held onto the old ways were asked to retire.

Yet, the traditional cantorial style of singing, much like other aspects of yiddishkeit, never completely died, as a handful of younger people continued to find joy in listening to old vinyl records from that era and held onto memories of this kind of liturgical music from their childhood.

One of these people made it his personal mission to make sure it found a new audience.

That man, Jeremiah Lockwood, is the grandson of a traditional cantor, the late Jacob Konigsberg. Lockwood fondly remembers listening to old cantorial records with his grandfather in Queens — an experience he described in a 2021 interview with the Forward. “There’s a certain richness and blooming of sound that I associate with the smell of pipe smoke, the way the smoke would waft through the air in the back room of my grandfather’s study in his apartment in Forest Hills and a lot of my musical pursuits have been around trying to recreate that feeling.”

This passion inspired Lockwood to create the internationally touring band, The Sway Machinery, in 2006, which not-so-subtly incorporated the sounds of old style cantorial music into blues and Afro-funk, as you can hear in his 2008 song “Avinu Malkeinu Z’khor,” boldly including the High Holy Day prayer in a mainstream album. This way, Lockwood was able to introduce the music to audiences outside of the closed channels of Jewish communal life.

But he wasn’t satisfied with that.

After enrolling in a doctoral program at Stanford University, he discovered, while listening to YouTube clips, that there was a circle of young Hasidim in Brooklyn who met in one another’s homes, singing and improvising khazzones. They did this in defiance of their community, which had also taken on pop and folk as the dominant modes of prayer music. Astonishingly, most of these khazzonim learned the style by listening to old records so that they could catch as many of the nuances as possible. “They train their bodies to make the sounds,” Lockwood explained.

Lockwood found his way into this group of khazzonim, and decided to record an album with them, “Golden Ages: Brooklyn Chassidic Cantorial Revival Today.” It was released this past June, accompanied by a forthcoming book — all part of his doctoral dissertation. Yanky Lemmer, Shimmy Miller, Yossi Pomerantz, Yoel Kohn (who left the Hasidic world but still pursues the craft), Yoel Pollack and David Reich all have tracks on the album, accompanied by organ, and sometimes each other as meshorerim (choristers). A number of the group performed at the Jewish Cultural Festival in Krakow, which also distributes the record in vinyl and digital download, where they wowed the audience with this old-new musical sound.

Inspired by their talent, Lockwood decided to record them at Daptone Studios in Brooklyn, a legendary home for soul and funk, right before the pandemic hit. But the analog recording was uncomfortable for the singers, Lockwood said, given that they were used to the luxury of digital, where they could easily fix notes or sections that went wrong. Lockwood felt that perfection wasn’t the goal here — authenticity was. He knew that the Daptone recording engineers were “the best in the business,” and he wanted to challenge the khazzonim to do full, uninterrupted takes, putting their hearts into it. Some of the singers improvised parts of the music, capturing the spontaneity that was characteristic of the traditional cantors’ performances. The results are breathtaking — especially Yoel Kohn, who seems to have picked up all the techniques of yesteryear.

Kohn stresses the need to react to the words. “Thinking about the words and contextualizing it helps a lot to just make the music be what it wants to be,” he wrote in an email. Words like “mah lanu mah chayenu,” (who are we to You? What is our life to You?) in Kohn’s performance of “L’olam Yehey Odom” (At All Times, Man Should Fear God) composed by Yehoshua Vider, moves Kohn to feel “the emotion of helplessness before the enormity of existence.”

What’s most striking is the emotional abandon one hears throughout the album, an embrace of what Lockwood calls an “anti-conformist worldview,” one that doesn’t stick to rote and perfect form. When the Golden Age style is performed faithfully, you can hear the cantor’s inner thoughts and feelings in heartrending moments in the song. “Suddenly things that aren’t emotionally charged become that way,” Lockwood says.