The blossoming and annihilation of the Jews in Tarnow

Before the Holocaust, Jews and Poles were on good terms, but under German occupation, many Poles aided the Nazis.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Recently, a number of books and articles have been published in the relatively new genre called micro-history, in which researchers focus on an individual, event or community in a specific era and location as a way of illustrating the larger picture.

One book that takes this approach, in German, is “Only Memories and Stones Remained: The Life and Death of the Polish-Jewish City of Tarnow, 1918-1945,” written by historian Agnieszka Wierzcholska, based on her doctorate from the Free University in Berlin.

In 1936, about 25,000 Jews lived in Tarnow — about half the city’s population. Between the two world wars, Jewish political parties were much more active in local politics than on the national level. When the Jewish Labor Bund expressed solidarity with the Polish socialists on the Tarnow city council, Zionists interpreted it as a blow to Jewish unity. It’s worth noting that despite the increase in antisemitism in Poland towards the end of the 1930s, the antisemitic political parties had very little support in Tarnow — a sign, writes Wierzcholska, that Jews were deeply integrated in local politics.

Jewish parents in Poland had various options for schooling their children. The Polish government created schools for Jewish children taught in Polish. Their day of rest was Saturday rather than Sunday. The majority of Jewish children, though — more than 80 percent — attended Polish government middle schools. These schools were free and prepared students for becoming part of the fabric of Polish society. One such school was the Czacki School, located in Grabowska, a poor and working-class Jewish neighborhood. About half the students were Jewish, mostly from needy families.

Records of the Czacki School’s meetings provide insight into the school’s daily concerns. “By reading those records, one gets the impression that it was mostly the Jewish students who had trouble keeping up with the classwork, were frequently late to class, and were dirty,” writes Wierzcholska. The Jewish students didn’t speak Polish well and chatted to each other in Yiddish. They often missed class on Saturdays or misbehaved. The Polish teachers called them lazy and negligent with their hygiene.

This attitude was similar to the general antisemitic biases in Poland, especially in the 1930s. People didn’t value cultural and religious diversity and instead regarded Jews as outsiders who needed to be turned into good Polish citizens. In the Staszic School, where 50% of students were from needy Jewish families, more attention was paid to helping them master Polish and overcome other obstacles. The school’s genial director played an important role in the treatment of Jewish students, the author surmised.

After the required seven years of middle school, students had the option to continue their education in a gymnasium (a European high school), which required tuition. Jewish children from well-to-do families could attend the bilingual Polish-Hebrew private school, Safa Berura. In contrast to the Polish gymnasiums, Safa Berura was coed. Ideologically the school was secular Zionist but its goal was to educate Jews who were loyal Polish citizens, yet proud Jews as well.

The dream of Polish-Jewish coexistence vanished with the breakout of World War II. The Germans invaded Tarnow on Sept. 7, 1939. The second half of Wierzcholska’s book details daily life under German occupation. Just like in the first part of the book, the author devotes a good deal to the relations between Poles and Jews. In 1940, the Germans deported the political, spiritual, and cultural elite of Poland to Auschwitz. Many other Poles were forced into slave labor.

The fate of the Jews was much worse. Right after the start of the occupation, Jews were locked out of all economic and public activities. On Nov. 9, 1939, one year after Kristallnacht in Germany, the Germans burned and destroyed every synagogue. The systematic murder of Jews started after June 1941, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union. The first Jewish victims were those who fled to the Soviet Union in 1939, and then returned to Tarnow. There was no ghetto in Tarnow until the summer of 1942. Until then, Jews and Poles still lived as neighbors.

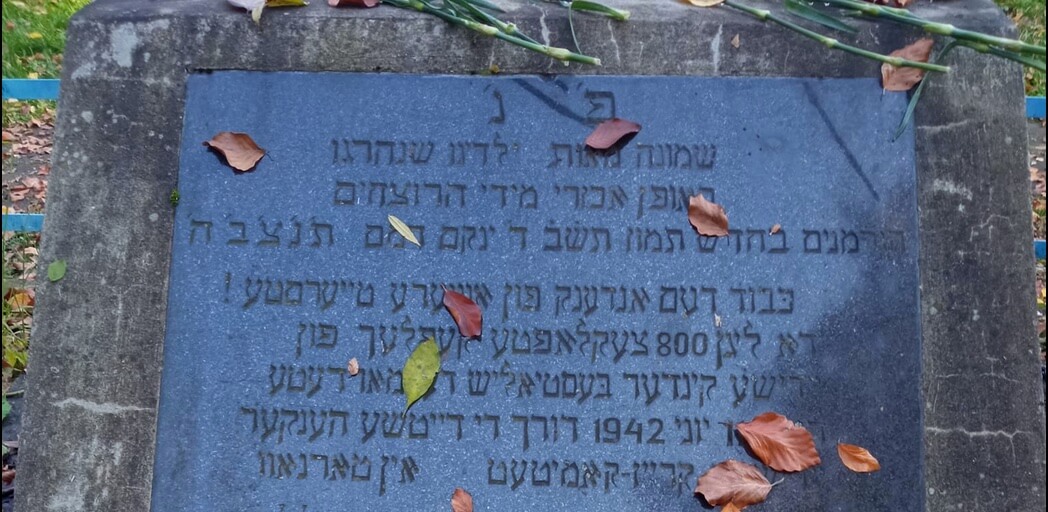

The mass deportation of Jews started on June 11, 1942, when the Germans drove hundreds of Jews into the town marketplace, and from there to the Belzec death camp. Other Jews were murdered in the street or at home by Nazis, occasionally aided by the victims’ own neighbors. Most Poles didn’t actively participate in the mass murder of the Jews, but did plunder the possessions they left behind.

The issue of guilt of bystanders who witnessed but didn’t actively participate in the Holocaust, is morally and historically complicated. Wierzcholska demonstrates that many Polish citizens helped Germans identify Jews who tried to escape from the ghetto, since the Germans were often unable to tell the difference between a Jew and a Pole.

Wierzcholska pieces together the history of the annihilation of the Jews of Tarnow through hundreds of anecdotes and facts taken from private memoirs, interviews, archival documents, news reports and other sources. We hear a chorus of Jewish and non-Jewish voices sharing memories while the photographs provide a glimpse of the faces and homes that once enlivened Tarnow.

In the broader narrative of the history of Jews in Poland, Tarnow was no exception. But Wiercholska’s important research reveals some of the individual fates that would otherwise remain unseen, allowing readers to understand what it was like to live through this tragedy.