Striking illustrations set in a timeless shtetl

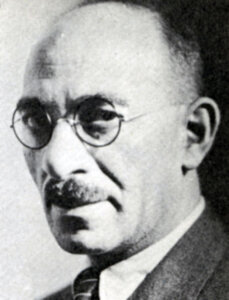

Joseph Budko created his art in the golden age for illustrated Jewish books between 1910 and 1940.

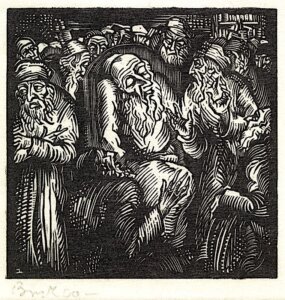

Joseph Budko’s 1923 woodcut illustrating Samuel Lewin’s book, “Chassidische Legenden” (Chasidic Legends) Courtesy of Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme in Paris (mahJ)

The era between 1910 and 1940 was a golden age for illustrated Jewish books. It was a moment when Jewish literary and artistic creativity burst forth hand in hand, each immensely enriching the other.

Of the many artists who devoted their talents to book illustration, a few — such as Marc Chagall and El Lissitzky — later found acclaim as painters and remained well-known. But others poured their talent into illustrating Jewish texts, whose audience was more limited — and shrank even more after the Holocaust.

Among the most compelling of these nearly forgotten illustrators of Jewish books was Joseph Budko. He was born in Poland in about 1888 but was most active in Berlin and later in Jerusalem. He was extremely prolific, particularly during the early 1920s. He produced striking images for German translations of literary works by key Yiddish and Hebrew authors like Sholem Aleichem, Sholem Asch and Hayim Nahman Bialik.

Budko also created inventive pictorial cycles for traditional religious texts such as the Haggadah and the Psalms. His woodcuts, engravings and etchings were stylistically attuned to broader artistic trends of the first decades of the 20th century. They feature the angular forms, flattened picture plane, strong black-and-white contrasts and emotional expressiveness characteristic of graphic work by his contemporaries.

But his subjects were almost entirely Jewish. He thought deeply for many years about the meaning of “Jewish art” and eloquently expressed his convictions in writing as well as visually. For Jewish readers, accustomed to privileging the written word, Budko’s illustrations infused Jewish imagery with new prominence. For non-Jews who knew of his achievements, his assured modernist style brought Jewish subject matter into the cultural mainstream.

Budko’s transition from yeshiva student to art student

Budko was born in Plonsk, Poland, probably in 1888 — though some sources say 1880. He was from a traditional Jewish family and had a thorough religious education. Published sources don’t make clear when or how he became interested in art. But an anecdote described below shows that he was already drawing portraits as a young man in Plonsk. Intriguing questions, such as how his traditionally observant family responded to his passion and talent for art, remain unanswered.

Sometime before 1909 he relocated to Warsaw. There he drew an arresting profile portrait of the great Yiddish writer, I. L. Peretz — though the specific connection between these two creative men remains tantalizingly uncertain. By 1909 Budko had settled in Berlin and begun to study graphic art with the innovative German-Jewish artist, Hermann Struck — one of Chagall’s printmaking teachers.

In October 1919, after living in Berlin for 10 years, Budko published a fascinating article in German for the New Jewish Monthly Journal. The entire issue was devoted to the theme of Jewish books, which Budko interpreted in an unconventional way. He saw them not only as texts made up of words, but also as creative visual imagery. And to be a specifically Jewish “book,” this imagery needed to capture the “essence” of Jewishness — a concept he began to define as a young artist in Plonsk.

A Talmudic Scholar opens Budko’s eyes

In his article, he described a conversation he had there with an elderly Talmudic scholar (a friend of his father’s). The scholar watched him drawing the heads of Jews, suggesting perhaps that Budko’s family was accepting of his art. The old man complained that the youthful draftsman was merely portraying the external appearance of these Jews and not their internal “essence.” The drawings, as he quaintly put it, depicted only ordinary “jugs” and not what those worn and cracked vessels contained.

To capture this hidden but crucial essence — the inner spark that made a Jew a Jew — the old man gave him some advice. “Put down your drawing pad and go straight to the study house,” he said. By immersing himself in traditional texts and rituals (which Budko knew from his upbringing but had apparently neglected), the art student would reconnect with the Jewish essence, which the elderly scholar defined as the spiritual greatness of ancient Israel: the dignity and vitality of the ancient rabbis, which had been diluted in the shtetls by the humiliations of exile.

The elderly sage didn’t discourage Budko from making art. He simply wanted it to become a truly Jewish art informed by deep Jewish traditions. Budko apparently followed his advice. By 1919 he had begun to make his unique contribution to the “book” of Jewish visual imagery.

Depicting images from a world that was quickly disappearing

Thanks to his employment by important Jewish publishers in Berlin, Budko crystallized his ideas about Jewish art by creating actual book illustrations. Most of his illustrations are set in a timeless and universal shtetl. The shtetl wasn’t specifically Plonsk, but the images hearkened back to his memories of a world that had already been severely damaged by the catastrophes of World War I. The mood is dark in every sense. He was a master of different gradations and tonalities of black, which he used liberally across graphic media. His figures seem caught out of time even when they are in motion. The atmosphere is often mysterious, sometimes mystical or vaguely disquieting.

Above all, each scene is permeated with a deeply Jewish tam — the Yiddish word for “taste” or “character.” Jewish dress and behaviors, and the streets and buildings where they played out the dramas of their lives, are closely observed. The dignity and intensity of the protagonists, embedded in their distinctively Jewish world, express the spiritual “greatness” that linked the Jews of modern Europe to their ancient forebears. This was the Jewish essence that Budko had spent long years learning to express.

Exquisite illustrations of righteous rabbis

A few representative examples give a sense of the quality and scope of his achievements as an illustrator:

• A 1921 engraving from the Haggadah portrays the rabbis of Bnei Brak seated around a table discussing the meaning of the Exodus. Their weighty bodies draped in voluminous robes look like they are carved from blocks of marble. Forming a tight circle in their deeply shadowed room, they seem unaware of the crowd of students reminding them to come to morning prayers.

• A 1923 woodcut illustrating Samuel Lewin’s book entitled Chassidische Legenden (Hasidic Legends): a group of pious Jewish men crowd around a frail, elderly rabbi who comments on a law or text with closed eyes. The intensity of the men’s devotion ripples through the vibrant black lines of the composition and the white spaces in between, filling the constricted visual plane with spiritual energy.

• A 1923 woodcut illustrating the German translation of Hayim Nahman Bialik‘s 1894 Hebrew poem, “On the Threshold of the Study House”: a solitary scholar gazes out the window into a velvety black night punctuated with stylized moon and stars. He has been reading a holy text by candlelight, and his large eyes set in a gaunt face look heavenward as he contemplates the significance of the sacred writing.

Despair over the deteriorating Jewish situation in Europe

• A 1923 engraving depicting the outside of a shul during Selichot (the recital of penitential prayers around the High Holidays), one of 12 illustrations of Jewish festivals from a book called The Year of the Jew: an extraordinary image executed almost entirely in gradations of black. A man and boy grope their way toward the dimly lit shul by lantern light, perhaps symbolizing the dark and difficult journey of repentance — or even Budko’s own journey back to a Jewishly-informed life.

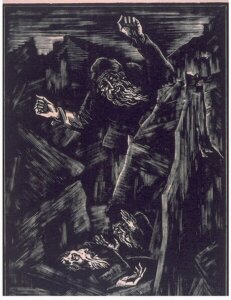

• A 1923 woodcut illustrating the German translation of Bialik’s enormously influential Hebrew poem, “In the City of Slaughter.” The poem, written in 1904 as a response to the 1903 Kishinev pogrom, is a searing indictment of what Bialik saw as the passivity of Jewish leaders in the face of anti-Jewish violence. The connection between Budko’s figures is ambiguous, but both are clearly Jewish men. The enormous, raging figure standing over the helpless victim lying broken in the street seems to be both mourning and menacing him. Budko illustrated more poems by Bialik than by any other author, and this image evokes their shared grief and despair over the deteriorating Jewish situation in Europe.

Budko’s fascination with ancient Israel brings him to Palestine

Budko lived in Berlin for 24 years, until Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany in 1933. Unsurprisingly, given Budko’s fascination with the spirit of ancient Israel and his kinship with Bialik, who had emigrated from Berlin to Palestine in 1924, he began a new life in Jerusalem. In 1934 he became director of the New Bezalel School for Arts and Crafts in Jerusalem — a position that allowed him to mentor many young artists, and which he held until his untimely death in 1940.

Once he was no longer employed by the Berlin book publishers he turned primarily to oil painting, sensitively depicting the Jews of Palestine surrounded by their distinctive landscapes and ancient stone architecture. Much of his energy was devoted to teaching and helping to build a dynamic art scene in Jerusalem. His quest to express the Jewish essence never diminished, but it found new and more varied outlets.

Interested readers can explore a strong collection of Budko’s prints online at the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme in Paris, better known by its acronym, MahJ.

To learn more about Budko’s life and work, watch this video of him, produced by he Yiddish writer and former Forverts editor, Boris Sandler.