The history of Orthodox Jewry needs to be told. Here’s what two scholars are doing about it.

The Birnbaum collection has thousands of letters from Albert Einstein, Theodore Herzl and other dignitaries, jammed into manila envelopes.

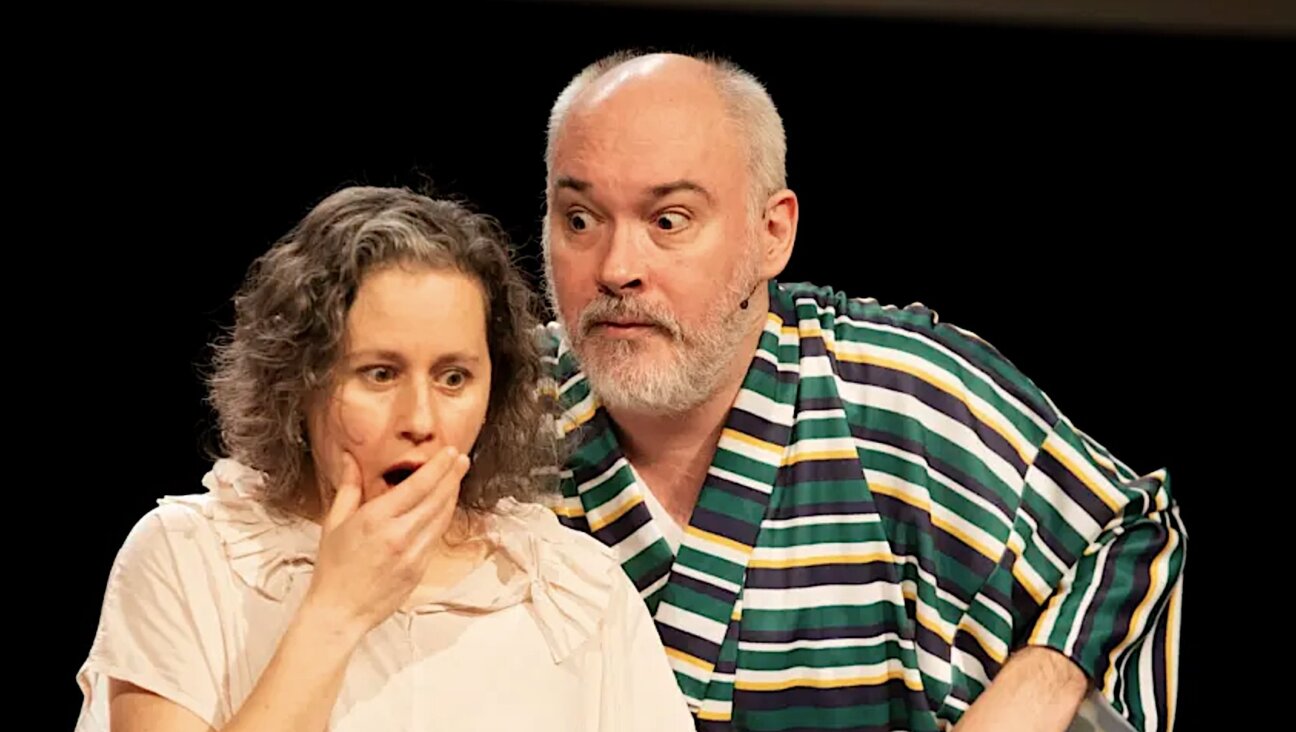

Naomi Seidman and Kalman Weiser looking through some rare town records at the home of David Birnbaum, in Toronto Photo by Albert Yang

The great scholar Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi once wrote, “History is the faith of fallen Jews.”

By “fallen Jews,” he no doubt had himself and many other secular Jews in mind. But what of Jews who are not fallen? Don’t religious Jews need history too? The secular nationalists and socialists who organized YIVO in Vilna in 1925 collected materials from all kinds of Jews, worried that Jewish heritage might disappear under the juggernaut of modernization.

Vilna’s famed Strashun Library offered Jews versed in the Torah and Talmud access to a huge collection of sacred Hebrew books. But Orthodox Jewish historians were few then, and very little of the material they collected survived the Holocaust. Today Orthodoxy is a growing field of study among professors and amateur researchers alike. But we generally have to mine collections devoted to other topics to find archival sources related to Orthodox Judaism.

That’s one reason the Nathan and Solomon Birnbaum Archives in Toronto is so exceptional. And why the two of us, scholars with a special interest in Orthodox Judaism and the distinguished Birnbaum family, feel so fortunate to be able to visit it, as we did on a recent snowy Thursday afternoon.

The collection is actually much more than an archive. Named after the Austrian-Jewish thinker Nathan Birnbaum and his son, Jewish language scholar Solomon Birnbaum, it consists of books, documents and art that bears witness to the Jewish political and cultural history of the 20th century. This includes the birth of Zionism, Yiddishism, the Orthodox political organization Agudath Israel and the activism on behalf of Soviet Jewry in the tumultuous 1960s in New York.

Like Zelig, the Birnbaums were everywhere

The collection does all this through the experiences of three generations of one remarkable family that became frum (pious) along the way. Like the main character in Woody Allen’s film Zelig, the Birnbaums seemed to have been everywhere, known everyone. While sadly not all members of the Birnbaum family escaped Hitler, the collection itself did.

Solomon Birnbaum, the first Yiddish professor in a modern university, brought his own and his father’s papers and books to London when he fled Hamburg in early 1933. In 1970, he transported the collection to Toronto, where he, his wife Irene Rikl and son David relocated, after another son, Eleazar (1929-2019), was appointed professor of Turkish and Near Eastern Studies at the University of Toronto. The oldest son, Jacob (1926-2014), started the first grassroots organization in support of Soviet Jewry in his Washington Heights apartment: the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry. A daughter, Eva, who was born in Hamburg in 1928, still lives in England.

Nathan Birnbaum (1864-1937) — the patriarch of the storied family — was the one who coined the term Zionism in Vienna, long before Herzl. But after a change of heart, he embraced the Diaspora and convened the landmark First Yiddish Language Conference in Czernowitz in 1908. Then, to the astonishment of his peers, he became a ba’al teshuvah (a secular Jew who becomes observant), soon serving as general secretary of Agudath Israel.

Promoting farming among the Orthodox

Nathan was not content to just be religious. He also wanted to transform Orthodoxy, to strengthen its passion and self-confidence and create a culture of Jewish artists and visionaries. Rejecting the urbanized Jewish life of that period, he promoted Jewish farming communities of mystics and seekers.

Of Nathan’s three sons, Solomon (1891-1989) most closely followed his path of religious “return,” becoming not only a pious Jew but an ardent admirer of the Eastern European Orthodox way of life, like his father. He developed his own “Orthodox” school of Yiddish linguistics that rejected the “assimilationism” and language standardization of YIVO. It was his spelling system that was used in the Bais Yaakov girls’ schools in prewar Poland. A pioneering expert in Hebrew paleography — the history of Hebrew scripts — he also authenticated and dated the Dead Sea Scrolls before the application of radiocarbon dating – by studying the handwriting style of the scribes.

It was Solomon who saved his father’s papers and his own when he left Nazi Germany in 1933. He also rescued much of the artwork of his brothers. Uriel Birnbaum (1894-1956), who survived the war in hiding in Holland, was a painter, illustrator, poet and writer whose work is displayed in museums around the world. Menachem Birnbaum (1893-1944?), who perished with his family in Auschwitz, was also a well-known artist specializing in Jewish themes.

Solomon’s son David, who still lives in Toronto, is the unsung hero of the collection. A retired architect and urban planner who quips in an English accent, David has devoted himself, since his father’s 1989 death, to organizing, alphabetizing, labeling and cataloging the material. “And adding to it,” he reminded us, when we praise his work.

Thousands of letters from Albert Einstein, Theodore Herzl and other dignitaries

David corresponds with scholars, provides advice about their research and writing, and collects the publications they produce. It’s hard work, but also rewarding, he said. “I’ve met a lot of very interesting people, not just you two,” he joked, over English tea and cookies at the dining room table in his modest home.

This visit was different: We weren’t doing research but preparing a display of items from the Birnbaum collection for a private event at the University of Toronto’s Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. David Birnbaum is approaching 90. Understandably, the future of the collection weighs on his mind. And on ours. As local professors with a passionate stake in its holdings, we’re hoping to find the collection a home at the University of Toronto, a university with a flourishing Jewish Studies program and the place where his brother Eleazar taught for years.

Spanning multiple bedrooms as well as the low-ceiling basement that was once Solomon’s study, the family archive is a mammoth collection containing thousands of letters from Albert Einstein, Theodore Herzl, Sholom Aleichem, Max Weinreich and many others, jammed into manila envelopes in old filing cabinets. Heading downstairs to the basement, where most of the collection is stored, was, as always, a little overwhelming. It isn’t easy to tell this story with just a few dozen items. Every minute or so one of us would pop up from a file cabinet to ask, “Have you seen this?”

The Birnbaum basement could keep grad students and scholars busy for decades

We went back and forth: “Buber or Bialik?” “Telegram or postcard?” There was a letter from Sarah Schenirer, the founder of the Beis Yaakov school system for girls. A definite keeper. Another letter from the Israeli Nobel Prize winner S. Y. Agnon, a postcard from Sholem Aleichem with a humorous drawing of a Hasid, a telegram from the German-Jewish philosopher Martin Buber. There were illustrations, posters and photos upon photos.

The Birnbaums are no ordinary family. What their basement holds can keep a legion of graduate students and scholars busy for decades to come.

As we waved to David at the door and drove away through the snow, we felt a pang for the collection as we’ve come to know it, among the everyday belongings of the family that so long guarded these stories. We know that these treasures deserve professional curation, temperature control, digitization, a place that scholars can get to without taking a taxi. Most of the archives and collections we’ve visited have those bells and whistles, and all of them have dedicated archivists and librarians who help us find what we’re looking for. But what David gives us is something different, some connection to the Jewish past that we archive rats are looking for, whether we know it or not.

Naomi Seidman is the Jackman Humanities Professor at the Center for Diaspora and Transnational Studies at the University of Toronto. Kalman Weiser is the Silber Family Professor of Modern Jewish Studies and Director of the Koschitzky Centre for Jewish Studies at York University.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO