The experimental sound of the Hutchins Consort meets klezmer and Jewish music of the Renaissance

A set of scientifically designed violins so rare that most are in museums demonstrated their unique properties at a California concert

Selected members of the Hutchins Consort from left to right: Ruslan Biryukov, A.J. Fanning, Bethany Grace, Pete Jacobson, Steve Huber, Batya MacAdam-Somer, Sarah O’Brien and Joe McNalley. MacAdam-Somer and O’Brien did not play at “Yidl mit akht fidlen.” Not pictured: Linda Piatt and Tim McNalley played at the concert.

It was a Jewish music concert unlike any I’d ever seen before, mostly because the music itself was not the star of the show. The 25-year-old Hutchins Consort directed by founder Joe McNalley, dedicated to performing with one-of-a-kind violins, made the afternoon feel like a running experiment.

The concert, “Yidl mit akht fidlen” (Yidl with eight fiddles) took place at the Oasis Senior Center in Newport Beach, California, on April 16. The title, based off of the classic Yiddish film Yidl mitn fidl, alluded to the Jewish content of the program, as well as the eight special violins on stage. The program was an eclectic mix of klezmer, the Renaissance music of Jewish composer Salamone de Rossi and new pieces by composer and saxophonist Yochanan Sebastian Winston.

Violins unlike any other

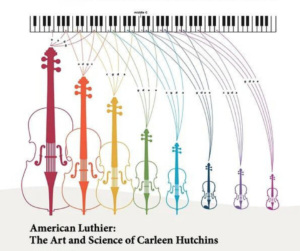

The Hutchins Consort was named after Carleen Hutchins, a scholar and artist who created eight scaled violins in the early 1960s, meaning violins that when played together, have access to six octaves — the range of classical Western music. This is unlike traditional ensembles with cellos and violas, which don’t cover the same range due to gaps in between their ranges.

Also, cellos and violas have different tonalities from a violin. A full range of violins without cellos, contrabasses or violas creates new possibilities in sound that never existed before the 1960s. The sound they create possesses a massive amount of harmonic resonances, which can destroy or glorify any piece of music.

Back and forth through the centuries

The Consort alternated between the music of de Rossi, the court musician of early 17th century Mantua, Italy, and klezmer of the early 20th century for the first half of the concert. That pairing, which had the potential to be jarring, was not.

What was jarring was how long it took for the musicians to hear each other, which they must have been hard-pressed to do considering the overwhelming overtones of their instruments. Before they pulled it together about five pieces in with the lively klezmer standard “Heyser Bulgar,” they seemed to resemble a haunted carnival band with clashing notes and mysterious overtones that gave the music an eerie feeling.

“Al Naharot Bavel,” which followed “Heyser Bulgar,” is one of de Rossi’s most celebrated works in his 1623 collection of Hebrew liturgical music Songs of Solomon. It was played at nearly half the speed of its choral arrangement, and its performance benefitted from this decision, allowing the violinists to really hear each other.

There is a section in the somber Psalm, which bewails the Jewish exile to Babylon, that did not express the bitter feeling of the original words but instead drove home the splendor of de Rossi’s magnificent harmonies.

Later, soprano violinist Bethany Grace stepped up from the line of violinists (and guitarist Tim McNalley) to speak about what the 1925 song “My Yiddishe Momme” means to her. Grace said that the last time she saw her Jewish musician mother, she played

this at an event at their temple, with her mom in attendance. When Grace began to perform the piece at the Hutchins event, it was as if she poured her life into her violin in her mother’s memory.

Tension with tradition

The instruments fared well with Winston’s modern classical music — though it certainly upset one patron who went up to Joe McNalley after the concert asking why a string version of Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze” and an even more abstract Philip Glass-like piece called “2023” were included in a concert which, up until intermission, featured only works from before the 1930s. I should not have been surprised that these were a prominent part of the concert — new instruments would naturally perform best with new music; music composed to tame and harness the extraneous resonances is repetitive and not tonally diverse, which is what these latter pieces were.

If you’re curious to hear what your favorite pieces of classical or world music could sound like with eight scaled violins that you won’t find anywhere else, look to the Hutchins Consort and their New York-based counterpart Hutchins Consort East. The fascinating and unpredictable outcomes may not make for smooth listening, but experiments — even decades-long ones — are spectacles in their own right.