Blending Yiddish calligraphy with watercolor, drawing and collage

Czech-born Karolina Kašeová’s art includes original portraits of renowned authors created out of their own words.

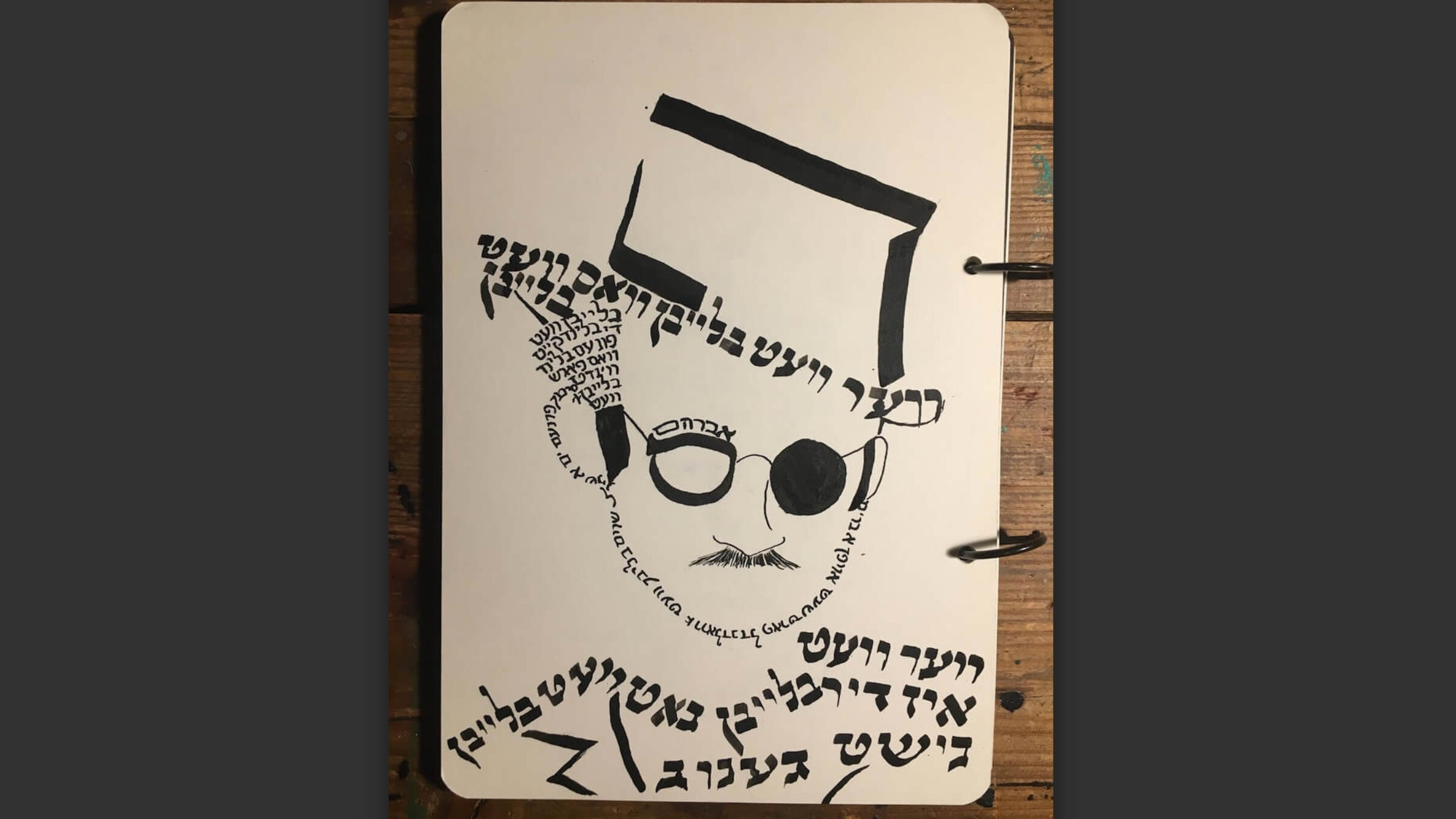

Karolina Kašeová’s portrait of the poet Avrom Sutzkever is made up of words from his renowned poem “Ver vet blaybn?” (“Who will remain?”) Photo by Karolina Kašeová

Karolina Kašeová doesn’t consider herself an artist. But her growing number of admirers, particularly among Yiddish enthusiasts, would disagree. She’s known for her vibrant and original Yiddish calligraphy, which combines hand-inked words and phrases with drawing, watercolor and collage.

I first met Kašeová and learned about her calligraphy in an online summer Yiddish class. It was intriguing that she lived in Prague, and I wondered what her Yiddish story was. We eventually connected on Zoom, and talked for hours about her life and art.

Kašeová’s calligraphy is rooted in unearthing her Jewish heritage. Her mother, Martina, descends from the prominent Guth-Weissberger family. Many Czech Jews lost their sense of identity under the double blows of the Holocaust and Communism, which criminalized practicing Judaism. Kašeová was born in the post-Communist 1990s, and grew up knowing she was Jewish — but in a fragmented and confusing way. Martina brought her to synagogue on Shabbos, but no one knew how to pray. Kašeová persisted in uncovering her family’s past and learning about Judaism, which became central to her identity.

She discovered Yiddish first through klezmer music, then through university work in Jewish studies. Although she didn’t know it at the time, illustrated books by Khalyastre and the Kultur-lige — avant-garde collectives active in Eastern Europe during the 1920s and ’30s — would later influence her calligraphy.

She loved the sheer chutzpah of avant-garde lettering

“The illustrations showed me how the Hebrew letters I knew from religious texts could be bent, stretched, twisted and embellished,” Kašeová told the Forward. (Two examples: the 1922 cover of Khalyastre’s magazine and the 1922 cover of Kultur-lige’s Oyf eyn fisele (“On One Little Foot”). “The ingenuity and sheer chutzpah of avant-garde lettering,” she said, “stood for everything that I admired about Yiddish literature: its energy, fearlessness and boundless inventiveness.”

When the COVID-19 lockdown hit in early 2020, Kašeová needed a creative and meditative activity to do at home — and she started making her own calligraphic art. She did a few pieces with Hebrew words, but mostly chose Yiddish as the basis of her calligraphy. “During lockdown,” she said, “the freedom and openness that I associated with Yiddish were irresistible.”

Her first pieces used the Yiddish word for an animal, skillfully combining the letters into an image of the animal. One example of this was הירש (hirsh = deer) with the 4 Hebrew characters making up the deer’s legs, body, horns and tail.

Kašeová also did portraits of authors out of words from their works, such as the face of the Yiddish poet, Avrom Sutzkever, created with phrases in his renowned poem “Ver vet blaybn?” (“Who Will Remain?”).

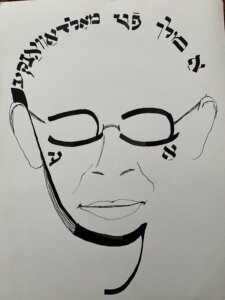

Another portrait, of the Russian Jewish writer Isaac Babel, uses his words from the Yiddish translation of his short story “The King,” about Jewish gangsters in Odesa.

A flower growing out of the mud

As online Yiddish classes proliferated during the lockdown, Kašeová encountered more and more Yiddish literature. “Sometimes the beauty of a particular quotation suggested a way to turn it into art. Other times, something resonated in my personal life or with events in the world. Yiddish literature was so often about contemporary concerns, about issues that deeply mattered to the authors and artists. So it felt right to reflect through Yiddish on issues that matter to me.”

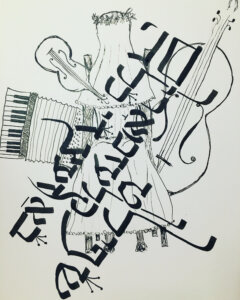

She made a piece combining words and musical imagery from the Yiddish song “Dray Tekhter” (“Three Daughters”) by Mordkhe Gebirtig. “The female figure with her face turned away, surrounded by swirling musical notes and instruments, suggests women’s lack of agency in traditional marriages such as the song describes.” It was also “unexpected and touching” to discover that Gebirtig, best known for his fiery political songs, “wrote so gently about girls and women.”

But her artwork also includes well-known Yiddish phrases that were not taken from an author’s work. One of these pieces expresses both despair and hope.

“The Yiddish phrase ‘alts iz blote,’ which literally means ‘everything is mud,’ suggests being trapped in a nonsensical world,” Kašeová said. “But I decided to suggest something else by showing a flower growing from the words about mud. The flower stem is made of the word ‘lomir,’ meaning ‘let us.’ So the image suggests blooming from the mud, creating hope from hopelessness.”

Her “Babyn Yar” is a response to the war in Ukraine

Lately Kašeová has been incorporating more collage. After a visit to explore Odesa’s complex Jewish heritage, she surrounded an old postcard of the city with the darkly humorous quotation from Sholem Aleichem: “Let’s talk about something more cheerful: Do you have any news about the cholera in Odesa?”

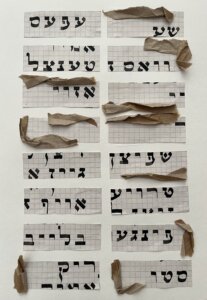

“Doorbells” was inspired by musician Daniel Kahn’s album “The Building,” and uses text by poet Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman about the destruction of Polish Jewry. “The cropped words on small pieces of paper — some nearly blank — are my tribute to the torn and fragmented lives that the poem and song commemorate,” Karolina said.

Her “Babyn Yar” is a response to the present war in Ukraine, and especially the March 2022 bombing that damaged the memorial to the Jews murdered there by the Nazis in 1941. “There’s anger and so much sadness in this work. I made up my own Yiddish text here about trees growing from the bodies of the dead, both in 1941 and in 2022.”

The beauty and limitations of feminine domesticity

A very recent piece, “Veyn Zhe, Veyn” (“Cry Then, Cry”), uses text from Mark Warshavsky’s touching folk song about a bride tremulously preparing for her wedding. “The baking sheet with outlines of challah suggests her new responsibilities as a married woman who oversees the Shabbos table,” Kašeová said. “And the frothy piece of an old white curtain evokes her wedding gown and the traditional world of feminine domesticity — with both its beauty and its limitations.”

Thus far, Kašeová has created around a hundred pieces of calligraphic art. She shares them mainly online, through Facebook and Instagram. As the world of Yiddish lovers becomes more interconnected by technology, her work is reaching audiences in the United States, Asia and Europe.

Wherever her future brings her, Yiddish calligraphy will be part of it. Yiddish, she says, is “my safe place, my home.”