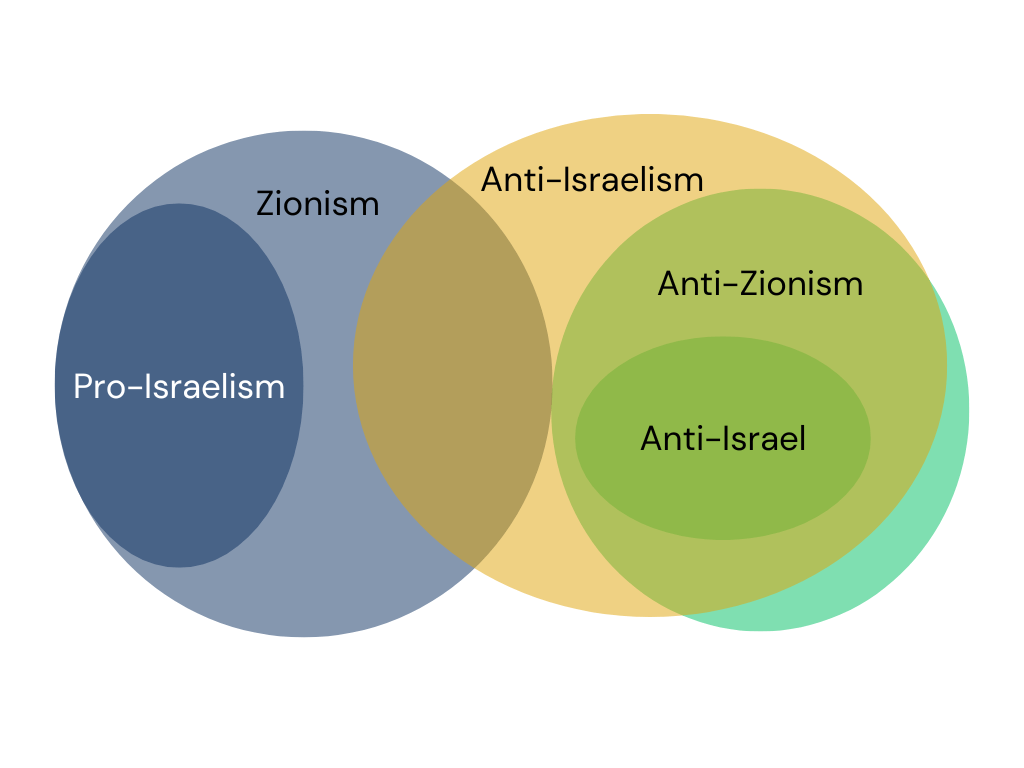

A Venn diagram to help us talk about Israel and antisemitism

The discourse is often split between “Zionist” and “anti-Zionist” — but we can do better

“Zionism is Fascism” is sprayed on a political office in Australia. Photo by Getty Images

“Antisemitism Notebook” is a weekly email newsletter from the Forward, sign-up here to receive the full newsletter in your inbox each Tuesday

TEL AVIV — I was discussing the vitriolic strain of anti-Zionism with a veteran journalist here last week, when he suggested that it might be best described as “anti-Israelism,” rather than “antisemitism.” That got me thinking about how limited our vocabulary is when it comes to talking about Israel’s supporters and critics, and when that criticism crosses a line.

When pro-Palestinian activists, for example, want to stop their participants in their movement from targeting random Jews, they often insist that “Zionism is not Judaism.” But this rather weak analysis can mark any Jew who isn’t avowedly “anti-Zionist” — dedicated to dismantling the Jewish state in Israel — as a legitimate political target.

And on the flip side, many pro-Israel leaders say that Zionism is integral to Judaism and they understand Zionism as going beyond a belief in the existence of Jewish state to include robust political support for Israel, suggesting this is the position of all American Jews who are not anti-Zionist.

We need better words, and I’ve taken a stab at a Venn diagram showing five ways that people relate to Israel.

Zionism

The belief that Jews have a right to a national homeland, and generally that the modern state of Israel should continue to serve this role. This position is held by the vast majority of American Jews.

Pro-Israelism

The belief held by some Zionists that Jews in the diaspora should support Israel with few conditions, erring on the side of promoting Israel’s security over other issues but leaving the specifics to Israeli Jews.

This is the position advocated by most major American Jewish organizations. Their leaders often refer to this stance as “Zionism,” although data suggests that many Jews do not share it — they see robust criticism of Israeli government policies as acceptable within Zionism, perhaps even an important part of supporting the existence of Israel as a Jewish state.

For example, Hillel International, the prime Jewish organization on college campuses, has exclusively expressed support for Israel during the current war. But Jewish college students — you might call them Hillel’s constituents — have a more mixed view. About two-thirds say there should be a Jewish state in Israel. But when asked whether they side with Israelis over Palestinians in the current conflict that share drops to 42%, suggesting about one-quarter of Jewish college students are Zionists that don’t align with Hillel’s “Israelist” approach.

Anti-Israelism

This is opposition to uncritical support of Israel, but not necessarily the core idea of Zionism. The share of anti-Zionist Jews in the U.S. likely hovers between 10% and 20%. But a much larger share opposes many of the positions held by Israeli government — and by the leading pro-Israel Jewish organizations.

For example, a May poll by an Israeli think tank found that nearly 30% of American Jews think Israel is committing genocide against the Palestinians, a claim that groups like the Anti-Defamation League and the American Jewish Committee consider to be deeply offensive (another 18% were unsure whether Israel’s actions should be considered genocide or not). The same poll, by the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, a right-leaning group focused on Israeli security, found that 52% of American Jews would support President Joe Biden conditioning military aid to Israel, and 22% would oppose it.

Anti-Zionism

The belief that Jews do not have a right to a national homeland, or at least that the state of Israel should not serve this role. Most political anti-Zionists are also anti-Israelists, but there are some religious anti-Zionists — like the Chabad movement — that actually express strong political support for Israel.

Anti-Israel

This final bucket refers to the subset of Israel’s critics who adhere to both anti-Israelism and anti-Zionism but also demonize Israel and Israeli Jews. They appear to have little interest in nuance or a humanistic approach to the conflict (think the folks who cheered on Oct. 7 or insist on referring to the country as “israhell”).

Why these categories matter

I have no illusions that people will start changing their terminology because of my diagram. But it can help us better understand antisemitism in relation to Israel.

Antisemitism cuts across all of these categories — many Christian Zionists have an ambivalent attitude toward Jews — and none of them are automatically antisemitic. But most of the concern over “campus antisemitism,” and similar protests off campus, is really about the “anti-Israel” agitators who view nuance as an affront and deny the humanity of Israeli Jews and those in the United States who don’t agree with them.

This is a distinct subset of Israel’s progressive critics. An Axios poll from May found that 52% of college students support a “free Palestine” and 45% backed the tent encampments (anti-Israelism). A smaller share would be properly labeled anti-Zionist (the 17% who said Israel does not have a right to exist). Another study around the same time found that 3% might be classified as avowedly “anti-Israel,” supporting violence toward Israeli civilians (some in this group were conservatives who did not support the protests).

The efforts to protect Jewish students, and American Jews in general, against this tiny last segment, has generally targeted the entire pro-Palestinian protest movement. A richer vocabulary could help people on both sides of the antisemitism debate.

Are “no Zionists” litmus tests meant to exclude liberal Jews who want to end military aid to Israel while also supporting a two-state solution? Should a college committed to protecting “Zionists” from discrimination focus on defending the most ardent pro-Israelists, or the vast majority of Jewish students who support Israel’s existence?

Better word choice alone won’t solve these conflicts. But precision should be in everyone’s interest.