‘Everybody needs to be uncomfortable’: Rachel Goldberg-Polin’s tireless campaign to bring her son home

How a hostage’s mother became the international face, voice and conscience of the war

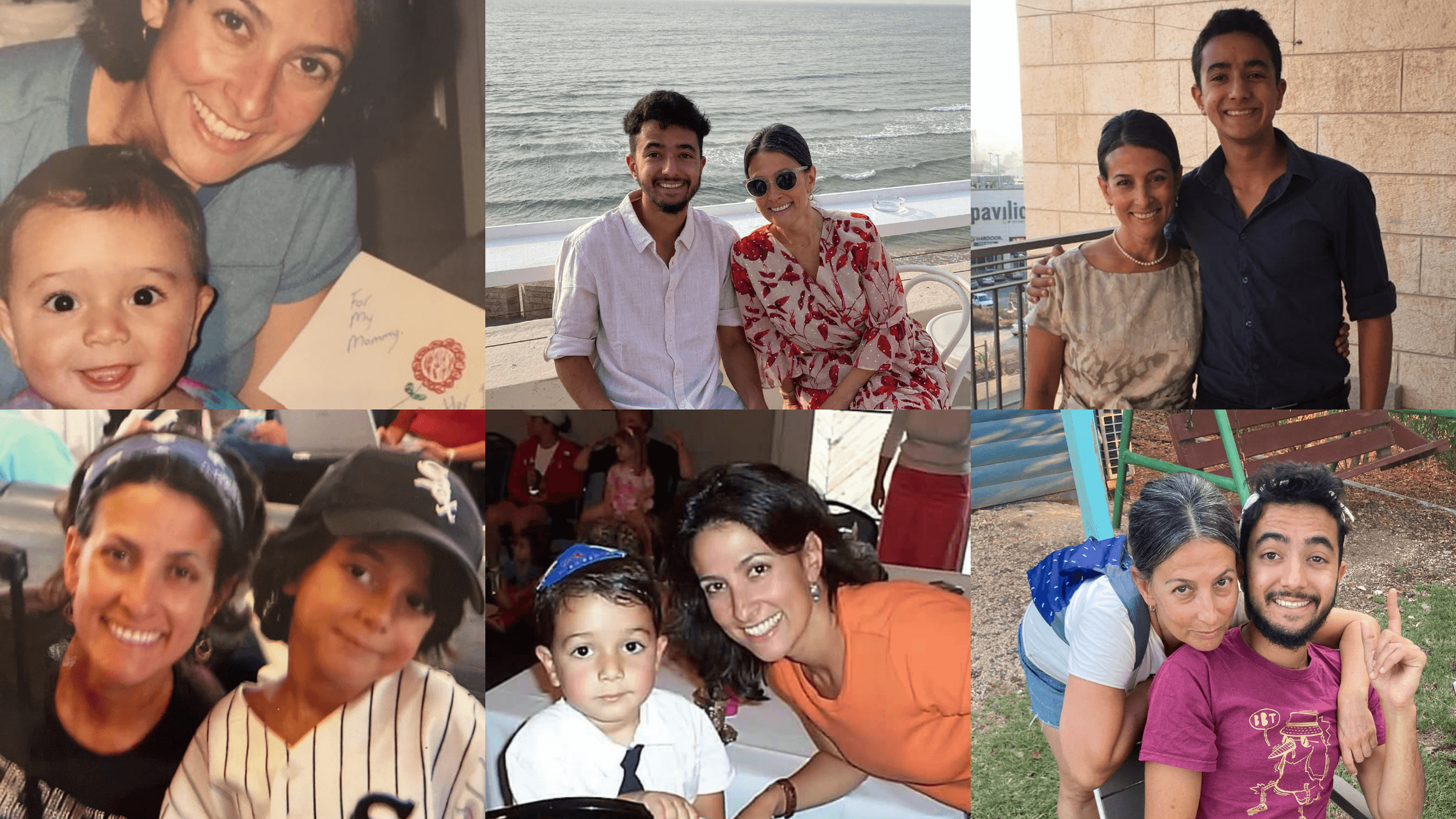

Rachel Goldberg-Polin with her son Hersh, who was abducted by Hamas terrorists. Graphic by Odeya Rosenband

JERUSALEM — The first thing Rachel Goldberg-Polin does when she wakes up each morning is go out on the deck of her top-floor apartment and change the numbers.

They’re big black numbers on white plastic, the kind you see listing gas prices or movie times on a marquee. Here, they hang off the railing next to a “Bring Hersh Home” banner, indicating the number of days since Goldberg-Polin’s 23-year-old son was abducted by Hamas terrorists.

Back inside, Goldberg-Polin makes herself a cup of tea and sticks a piece of tape with the number onto her pajamas. Maybe you’ve seen her with a number like that on her shirt, speaking at the pro-Israel rally in Washington (Day 39), meeting with Pope Francis (Day 47), reading a searing original poem at a United Nations human rights conference in Geneva (Day 67).

“It makes people very uncomfortable — it’s uncomfortable to look at a mother wearing a number of the days since her son was stolen from her,” Goldberg-Polin told me when we met at her home on Day 58. “It’s masking tape and a Sharpie. I would be fine with everybody doing it. Meaning, not hostage families — if everybody in America wanted to do it, everybody on planet Earth. Everybody needs to be uncomfortable.”

Goldberg-Polin, 54, a soft-spoken teacher who grew up in Chicago, is remarkably comfortable in the unwanted role she has inhabited since shortly after Oct. 7: the international voice, face and conscience of the hostage crisis.

A small woman with graying hair pulled back from her forlorn face, she mixes a relatable, everywoman appeal with flashes of profound wisdom and righteous anger in a constant-motion campaign.

She’s met with President Joe Biden and billionaire Elon Musk, delivered a nine-minute address to the United Nations General Assembly in New York and sung a lullaby at a rally in Tel Aviv. She’s been profiled in People magazine, The Atlantic and America: The Jesuit Review; written op-eds for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal; appeared on CNN, MSNBC, Fox Business, ABC Australia, WBEZ Chicago, TMZ Live and Sport5, Israel’s sports channel.

She’s had conversations with Mayim Bialik, Michael Rapaport, the Israeli film star Shuli Rand and the Australian actor Nate Buzolic. Countless Zoom events with American synagogues, briefings for volunteer missions to Israel, podcasts and social media videos.

“It’s almost like an animalistic drive: We try to stay very busy, and we try to do every single thing that we can think of to do on planet Earth that will save him,” she explained to a group of American rabbis visiting Jerusalem a few weeks ago.

“All the public speaking, all that stuff would have — before — made me very nervous,” she added when we spoke afterward. “My voice would have been shaking, I would have been panicked for weeks beforehand. That does not exist anymore. When you’ve been so traumatized and so terrified, nothing scares you anymore.”

On Day 70, the Israel Defense Forces mistakenly killed three Israeli hostages who were waving a makeshift white flag, men in their 20s like Hersh. The Goldberg-Polins have not made any public comments on the incident and declined to discuss it with me.

They’ve said that none of the more than 100 hostages released during last month’s weeklong pause in the fighting had shared any information about Hersh’s health or whereabouts.

“We hope and pray that the next time we’re interviewed,” Rachel said in a short video made Thursday (Day 76) and sent to journalists via WhatsApp, “Hersh will be right next to us.”

‘It’s a very primal, maternal-paternal drive’

You’ve probably heard the Goldberg-Polins’ story. How Hersh danced at Simchat Torah services that Friday before going with his childhood friend Aner Shapira to the Nova music festival. How Rachel turned her phone on Saturday morning to find an ominous pair of text messages from 8:11 a.m. “I love you guys.” “I’m sorry.”

How Aner, a soldier, died a hero in a roadside bomb shelter, blown up by a Hamas grenade after tossing back eight of them. How Hersh, a lefty, had his left arm blown off but managed to fashion a tourniquet before being whisked off to Gaza in a white pickup.

Maybe you’re one of the 62,000 people who follow @bring_hersh_home on Instagram or his 20,000 fans on Facebook. Maybe you’re among the 100,000 folks who have written to local elected officials pleading for help. Maybe you helped draw a “Free Hersh” graffiti mural or hoisted a Bring Hersh Home banner in Bremen, Germany, or Barcelona or Pittsburgh.

Maybe you’ve come to feel like you know Rachel and her son, who loves to read and to travel and to ask hard questions and is a die-hard fan of the Hapoel Jerusalem soccer team and has a Dec. 27 plane ticket booked for India to start a year-long trip.

Maybe you, like Rabbi Audrey Marcus-Berman of Temple Ohabei Shalom in Brookline, Massachusetts, see Rachel as “a very important leader of the Jewish people right now.”

“In my mind, you’re a neviah,” Marcus-Berman said admiringly during the rabbis’ meeting at the Shalom Hartman Institute, using the Hebrew word for a female prophet. “From where do you get the strength to do that — to immediately not only do everything you can to bring your son home, but to speak so powerfully and to lead us, to lead humanity, to fight this evil with such resilience and goodness.

“Whenever I see you saying something, I immediately post it,” she added. “I just want you to know it is seen by all of us.”

Rachel told the group that she sometimes goes to her room and screams into a T-shirt. That a few Fridays before meeting them, she’d had “a real breakdown” where “the noises coming out of me” had only occurred once before in her life: When she gave birth to Hersh, the first of her three children, without an epidural.

That she and Jon are “surrounded by savvy, gentle people who are carrying us when we are breaking.”

“If we have strength, it’s a very primal, maternal-paternal drive,” she said. “The pain, it’s a primal pain. I don’t know that we’re always strong. But I think that we feel this driven need to do whatever we can to save him. That’s where the strength comes from.”

‘It was the source of all my happiness’

Hersh was the first hostage I discovered a connection to: “Parents are vg friends,” my friend Jessica Steinberg, a journalist at The Times of Israel, messaged me on Oct. 10. She’d come across a 2015 article I’d done about the Red Cross working with Hamas in Gaza and wondered if I still had any contacts there who they might appeal to in hopes of getting Hersh medical attention for his arm.

I didn’t. But when I went to Israel last month, I learned many of my friends have Goldberg-Polin connections. They’d been at Shabbat dinner with Hersh before he left for the music festival. They’d seen Jon at the early minyan the next morning before the first siren went off. One of their kids was headed for a long weekend at the beach to celebrate the birthday of the younger of Hersh’s two sisters, Orly.

Everywhere I went in Jerusalem’s Baka district and the surrounding neighborhoods popular with Anglo immigrants, I saw big red “Bring Hersh Home” banners with his bearded mug hanging from stone balconies and store windows.

Rachel has not seen most of our mutual friends since this nightmare began. She has not been to the gym, or to shul, or on a walk through the neighborhood. The friend who drove me to her house for our interview texted to ask if he could come up to give her a quick hug. No, she wrote back, “hugs hurt me.”

Instead, she is usually surrounded by what they call the hamal, Hebrew for command center, up to 14 volunteers who have, since midday Oct. 7, been working on Team Hersh, an operation far more extensive than most hostage families have. Richard Demb, one of their oldest and closest friends, is chief of staff. Matt Krieger, who normally does PR for startups, handles the press. Rachel’s best friend’s daughter, Dahlia, is in charge of social media.

Dahlia’s mom, Cami, “is in charge of all the things you don’t think about,” Rachel said, like vacuuming the couch or washing the kitchen windows or buying more bleach.

A crowdfunding campaign on Jgive.com has raised $154,000 from more than 700 donors.

“Lunch shows up here every day — I haven’t cooked one thing since Oct. 6,” Rachel said. “Fruit platters show up, nuts show up. Everyone’s always asking for grocery lists, and then these groceries show up. I don’t know where the transportation comes from; somehow I am always transported.”

As she was escorted from the Shalom Hartman event, Rachel told me she did not know where she was speaking next. It reminded me of covering a presidential campaign, where the candidate only gets briefed about each stop on the itinerary just before arriving.

Rachel said she has come to dread Shabbat, when there’s less to do, fewer people around. On Friday nights, she goes out to the balcony where the numbers are and screams the traditional blessing over children, facing south toward Gaza, aching for Hersh. For the benefit of her two daughters, she’ll go to a friend’s home for a meal, but said it can “feel like my skin is being torn off.”

“I live this bifurcated life where I have to separate what I am feeling from behaving like a normal person so I can be with other human beings — it requires Herculean strength,” she told me.

“Because I loved Shabbat, loved,” she added, emphasizing the past tense. “The five of us, always Friday night we go to shul, it’s an 18-to-20-minute walk, that’s my favorite time of the week, we’re all together, no one has phones.

“It was the source of all my happiness — now it’s the makor of so much pain,” Rachel continued, inserting a Hebrew word for source that also means fountain or spring. “Each week that it’s an additional week that I cannot bless him in person.”

‘I need you to pray for him’

Rachel Goldberg and Jon Polin met when she was in eighth grade and he seventh at an Orthodox school in Chicago. Seven years later, they bumped into each other on Emek Refaim, Baka’s main strip of cafes and shops. She was studying at Pardes, a pluralistic yeshiva, and he was getting an MBA. Their parents laughed about them going 6,000 miles to meet the Jew next door.

They married and lived in Berkeley, California, and Richmond, Virginia, before moving to Jerusalem in 2008, when Hersh was 7. Jon, a high-tech entrepreneur, does a little less public speaking and more strategy and behind the scenes work on Team Hersh, like calling the Red Cross every day — to no avail — or lobbying lawmakers.

He was huddled at the dining room table with Demb while Rachel and I spoke, and would pipe into the conversation every once in a while. Like when I asked when she started wearing the taped numbers on her shirt.

“Day 26,” Jon said.

“Yes, Day 26,” Rachel agreed. “Someone was talking about how many days has it been, and I was like, ‘This is ridiculous, we need to know.’”

“We have different strengths,” she said of her husband. “There are things, every so often, where I realize he’s protecting me. Stuff he’s trying that I don’t know about. Information he ends up hearing that he doesn’t tell me.”

Since the abduction, she’s adopted the hyphenated last name “Goldberg-Polin” to feel closer to Hersh. At the Washington rally, she wore round sunglasses familiar from photos of her at the beach with Hersh that are among the hundreds of snapshots the family has shared online. In the Facebook videos, she’s usually seated on a plain white plastic chair, legs crossed tightly, speaking directly, personally, intimately to camera.

“I think Hersh feels recognizable as someone you know,” she offered when I asked why she thought their story had so captured the public imagination. “Everyone has known a Rachel Goldberg. There’s like 17 of us, and we all look like this.”

Rachel said she still davens privately each morning, sitting in the corner of the beige sectional sofa in the open living room. She finds herself focusing more on the prelude to the central Amidah prayer, the three Hebrew words that mean, “God, open up my lips, so my mouth may declare your glory.”

“It’s very anchoring,” she said. When she gets to the part that says, “redeem us,” Rachel said, “I say out loud, ‘Redeem Hersh.’ I do a lot of hand motions.”

In her speeches, Rachel often quotes from the Torah. She also always notes that the hostages came from many countries besides Israel, and include Christians, Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus as well as Jews. On Facebook, there were special videos connecting Hersh to each night of Hanukkah — and videos of Rachel marking each week of Advent.

She likes to sit in Hersh’s room, where the walls are plastered with Hapoel Jerusalem stickers. The book he was reading, the Dalai Lama’s The Art of Happiness, is on the nightstand; he was on Chapter 6, and the last thing he underlined is, “I was overcome with a profound sense of the interconnectedness and interdependence of all beings. I felt a softening.”

“I actually sent this to the Dalai Lama,” Rachel told me. Pointing to the headboard, where she placed a medal the Pope gave her, she added: “It can’t hurt.”

She is at turns hopeful and even a bit cheeky, imagining Hersh doing this or that with his new bionic arm, talking about the grandchildren he’ll have someday — and desperate, indignant, demanding more from politicians and the public.

“Where are the mothers?” she demanded in a video on Day 60. “In all of these rooms all over the world that decide the fate of all of us,” she said, “where are the women? I don’t think there’s any mothers in there. I think everyone at the negotiating table and in the war room, they should send their mothers instead of them.”

One recent night, she and Jon took a taxi home, and only had a 200 shekel bill, far more than the fare. “The driver apologized, and said: ‘Since the war, there’s no work, I don’t have change anymore,’” Rachel recalled. “I said, ‘Since the war, I don’t have my son anymore.’”

The driver, a Palestinian from the Jerusalem neighborhood of Tsur Baher, was befuddled. Rachel told him her story as Jon went to get change.

“It was important to me to say to him, ‘I know you don’t have anything to do with this,’” she added. “I said to him, ‘I need you to pray for him,’ and he said he would.”

Odeya Rosenband contributed research to this story.