Etgar Keret is writing again — and teaching an AI chatbot to do it better

Five months into the war, the Israeli author tries to imagine what his country will look like in five years.

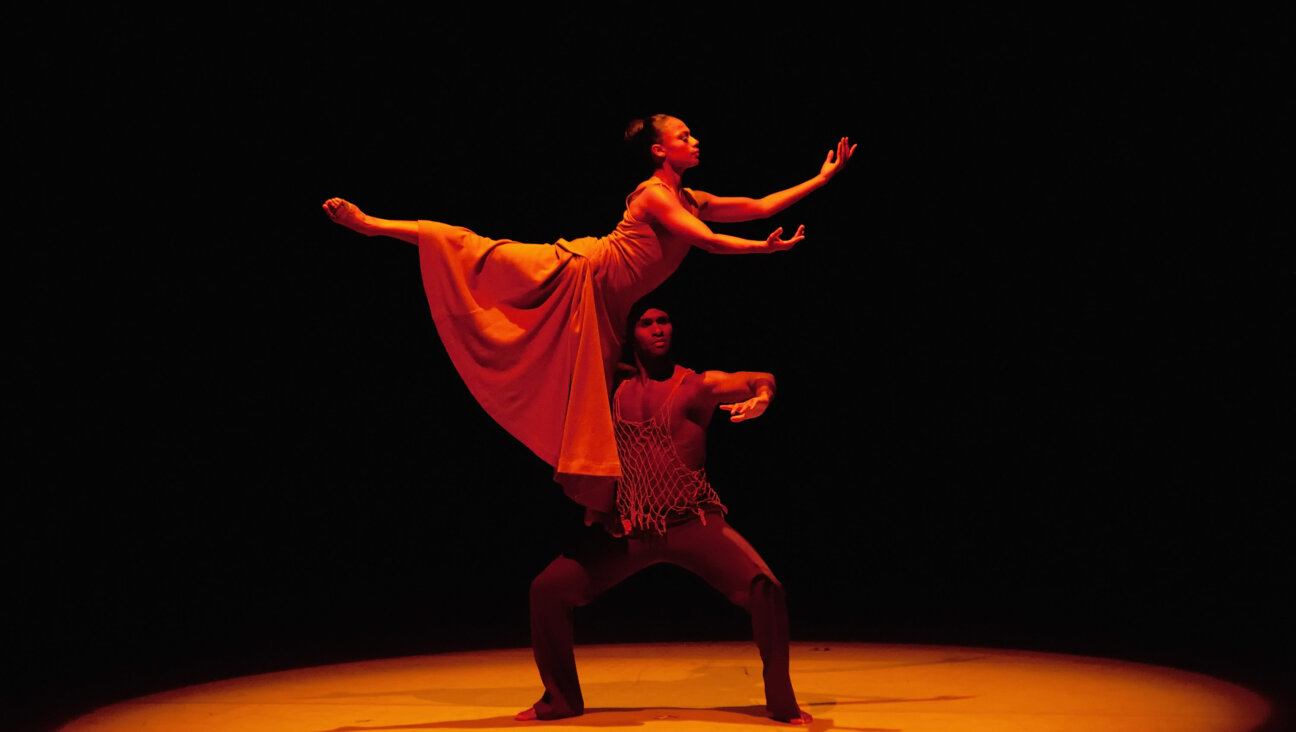

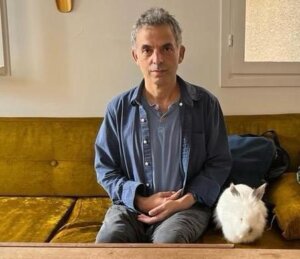

After Oct. 7 prompted months of writer’s block, Keret traveled around Israel doing impromptu readings for the traumatized. Courtesy of Etgar Keret

The first new story Etgar Keret wrote after Oct. 7 was about prayer. A “penniless, asthmatic bachelor” from Beit Shemesh loses faith because he prays with all his might but the hostages are not released. Then two are released, and so the man prays about marrying the “long-necked cashier” at the local supermarket.

She flashes him “a radiant smile,” they chat about kosher sushi. But before the bachelor can fulfill his vow to bring the cashier “a special rice vinegar” from Jerusalem, he dies, apparently of a brain bleed from when he fell on his forehead during fervent prayer.

“For me, writing has the function of praying,” Keret told me when we spoke last week. “If when you pray, you imagine God, when I write, I reimagine that there’s somebody who understands me, and who understands what I’m talking about much better than I will.

“It’s not that I write to deliver a clear message,” he added. “I deliver this scrambled message, kind of hoping that somebody out there will find something in it that I can’t articulate.”

I last spoke to Keret, my favorite Israeli writer, a dozen days after the Hamas terror attack, when he was experiencing his first writer’s block in 37 years and rushing around the country doing impromptu readings for the traumatized. I reached back out as the war approached its five-month mark because he always provides me with poetic insight to Israel’s psyche.

We spoke the morning of the deadly aid-convoy disaster in Gaza, as he was trying to finalize the cover for his seventh short story collection, Autocorrect, which publishes in Hebrew at the end of May (the English versions usually come a year later). He was preparing for a big event honoring his mother, who died four years ago, and is still doing readings for soldiers and evacuees.

He is also back teaching at Ben Gurion University — and working with researchers at Tel Aviv University on a project, as he put it, “trying to teach an AI how to write better fiction.”

What?

“We try to work on concentrated issues, like let’s say metaphors,” Keret attempted to explain. “Now I’m working with him on openings. I give him a premise for a story, and then I ask him to write the first paragraph. Then I read it, and I say to him, ‘Yeah, you know, but you’re telling the entire story in the paragraph.’ Or, ‘This is not interesting.’ Or this is unrelated, or this is cliche. I try sometimes to formulate rules that will help him, just to kind of make him do a little bit less bad.”

How’s that going?

“It’s half frustrating,” Keret said. “It’s not something that I’m doing and say, ‘Oh it’s amazing, it’s going to change the world. Half of the time I’m saying, ‘Wow, this was so vain of me.’”

I wondered why he’d want to help AI get better at writing fiction in the first place. Isn’t that exactly the kind of thing we think only humans can do well? And wouldn’t it, you know, be bad for business?

Somehow this led us to space travel.

“Once we said, ‘Oh if we can improve space travel, we can get further, we can know more.’ And then we say, ‘Ah, we have space travel so we can sell it to billionaires and they fly to space and do a selfie,’” Keret said. “There is something about our interaction with AI that is so self-indulgent. This thing can solve the biggest problem in the world, but the entire way that we conceptualize it is if it can draw a cute picture of a squirrel, or of our neighbor on fire.

“The more I deal with AI the more it gets me thinking of humanity,” he continued. “I thought to myself: Maybe the trick will be to help the AI understand the humanity better, and then it will make the hole bigger so we will be able to crawl through. It will leave us more space to be ourselves or not to change.”

Right, so how’s that going?

“My students are much, much more talented,” Keret said.

“Writing is an attempt to bring an individual thought to people that don’t think the same way,” he explained. “There is something about the way that the AI works, it’s built on statistics, it’s kind of wisdom of the crowd. So all the time it kind of says the thing that the biggest number of people would say. The effect of that is really kind of uninspired.”

Suddenly, it seemed we were back to talking about the war.

“Usually, the way you identify somebody who is missing is by her scars or by his birthmarks,” he noted. “Those things, they are the thing that the AI doesn’t have, because they are a mistake.

“The idea was that technology would help us have more free time and be ourselves. What happened is it pulls us away from being ourselves,” he explained. “AI can take something positive and turn it into something addictive. If I like to see sunsets, I can only see one a day. But with technology, I can see sunsets on loops. All the balancing mechanisms are being thrown away.”

Balancing mechanisms. Again it seemed like we were maybe also talking about Israel and Gaza. Keret, whose son Lev is slated to join the Israeli army in August, described “the Oct. 7 effect” as “very much the feeling of losing your equilibrium, this idea of kind of falling, losing your balance.”

“Usually, while you fall, you don’t have many interesting thoughts,” he said to explain his initial inability to write anything new. “But when you reach the ground, you can write a wonderful story lying on the floor.

“It’s not as if anything got better. In many senses, there are things that actually put me more into despair. But I have a better grasp of where I am or what’s going on.”

Now we were definitely talking about the war. He sees the conflict as global, not just “between two neighbors,” and says Israel is at a crucial “crossroads,” where “it seems the two sides that existed here before the war only became 100 times more convinced.”

“When people say to me, ‘Oh, but we tried peace once and we failed,’ I say to them, ‘How many times did we try war and we failed?’” Keret told me. “This is not the first time we conquered Gaza. Did they learn Yiddish in Sunday school? No.

“I’m not talking about the details, but to say, ‘Oh my God, things here are so amazing, we want things to stay the same, let’s just bomb Gaza a little more’, I don’t think is a viable solution,” he continued. “When I look at Israel five years from now, I can easily imagine it in a much worse place. But I can also imagine a scenario in which there is a change that comes from all this, that we don’t do more of the same, that this is really the last day of this kind of inciting politics.”

I wonder if there might be room at the negotiating table in Cairo for a fiction writer. Or, perhaps, the AI learning to understand humanity better.