Why I’m confident the war in Gaza won’t ruin another year on campus

New school policies and shifts in US politics hope to create a calmer campus environment this fall

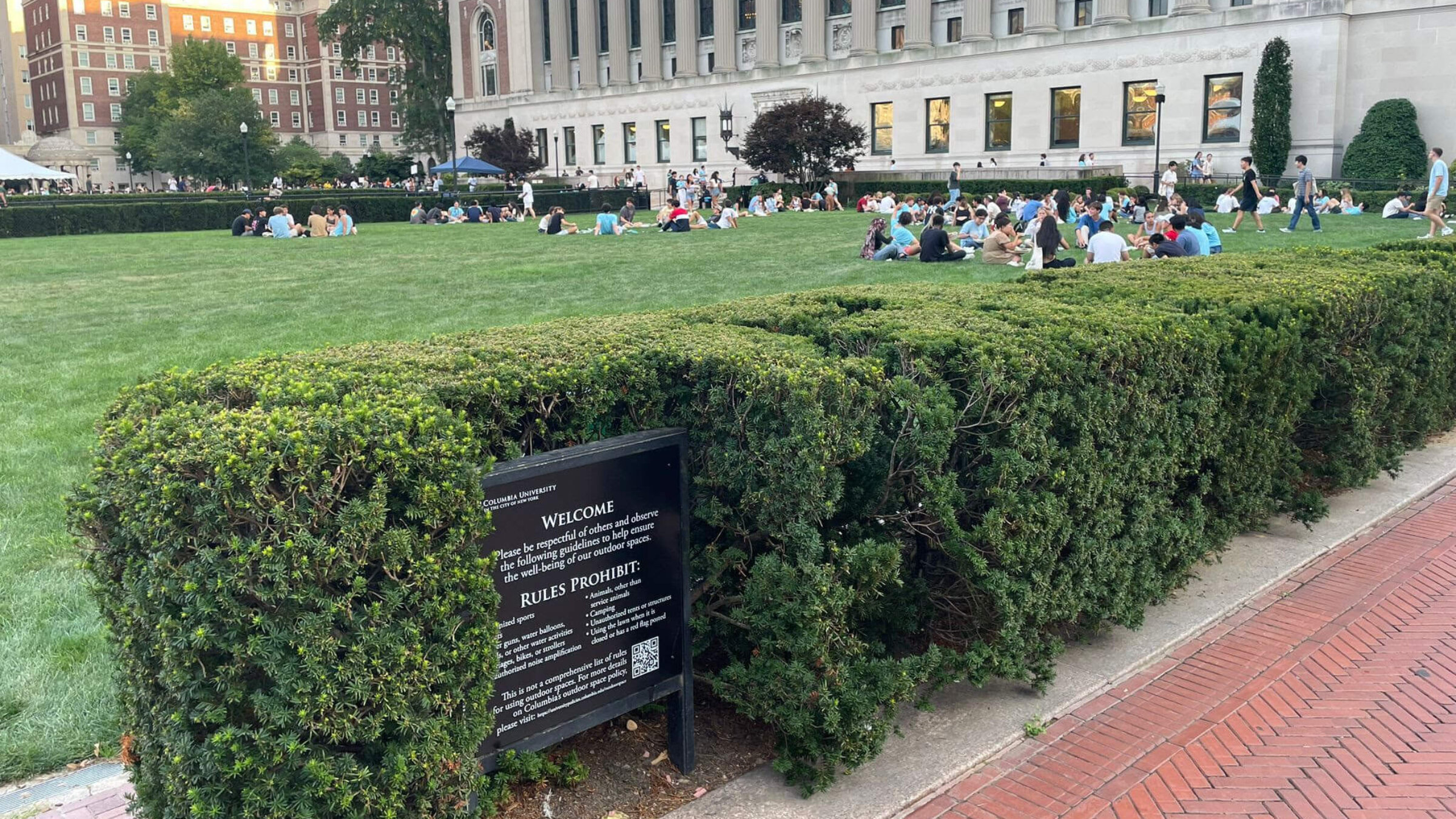

At Columbia, the heart of last spring’s encampment movement, the green that was filled with tents was calm this week, with a new sign showing rules including “no camping.” Photo by Columbia Student

PROVIDENCE, Rhode Island — Touring the campus of Brown University with my kid this week, there was nary a sign of the encampment or hunger strike protesting Israel’s war in Gaza that had roiled the place last spring. No Palestinian flags, no graffiti about genocide.

The only signs I saw on the main quad warned those gathered for orientation programs that photos were being taken to commemorate the proceedings. Oh, and a bunch of bulletin boards had fliers advertising Shabbat dinners.

Granted, most undergraduates had not yet returned to campus, as Brown classes don’t start until Wednesday. And I am keenly aware that a handful of other schools including Cornell, the University of Michigan and MIT have already seen flashes of anti-Israel and antisemitic actions.

Still, as summer turns to fall and we approach the anniversary of the horrific Hamas terror attack of Oct. 7 and the devastating war it spawned, I am cautiously optimistic that most colleges and universities will not again be dominated and disrupted by uncivil discourse over Israel-Palestine.

There are two distinct reasons for my confidence — and, yes, profound hope — that this year will be better than last on campus.

First, university officials have spent the summer clarifying or creating stronger policies delineating the boundaries between protected protest and harassing hate speech. These include time, place and manner restrictions — no tents or masks at lots of places — and also training on antisemitism and other scourges that stifle the kind of difficult conversations we need to keep having in the academy.

Second, the dramatic changes in U.S. politics have taken some of the wind out of a movement in which Gaza had become a proxy for a panoply of complaints from the American left. You could see this clearly at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago earlier this month, where pro-Palestinian protests fell far short of expectations and hardly distracted from the proceedings.

I am not saying, as too many pro-Israel Jews have dismissively done, that Gaza protesters do not actually know or care about Gaza; there is absolutely a strong, large core that does, and I expect them to continue to press forcefully for Palestinian rights, divestment from Israel and a U.S. arms embargo. But it’s equally clear that many of the thousands of students and others who camped out for days, risking suspension and arrest, were motivated by other issues, including police brutality and climate change, and the dynamics around those have shifted somewhat this summer.

The Gaza movement on campus last spring was, in many ways, a collective scream from the left over all that is wrong with the world. For many young liberals, President Joe Biden’s refusal to step aside despite his increasingly obvious inability to beat former President Donald Trump was a big part of that. Biden’s replacement at the top of the Democratic ticket by Vice President Kamala Harris has, for a lot of Gen Z, replaced that scream with a sigh of relief.

Given how much Gaza had become intertwined with Black Lives Matter, it’s hard to imagine the prospect of electing the first woman of color as leader of the free world will not divert some of these activists’ attention, at least until Nov. 5.

As I wrote last spring, I was profoundly disappointed in higher education leaders’ response to Oct. 7 and the uprising it spawned on many campuses.

My frustration was not, primarily, about Jewish students’ safety — I continue to think that the collective freakout about that among leaders of mainstream Jewish groups and some Jewish parents is overblown. But I thought university presidents and other senior officials shirked their core responsibility of provoking thoughtful, respectful inquiry and debate. Instead, they let screaming mobs snuff out the kinds of conversations colleges are built for.

So to gut-check my relative confidence about the return to campus this fall, I reached out to a top administrator at one of the elite schools riven by protests last spring, someone I know to be forthright and self-reflective. Annoyingly, they spoke on the condition that they and their institution not be named, a sign of how toxic this whole issue has become. But they did offer some insights worth sharing.

“Every campus in this country has rethought its institutional neutrality policy,” this administrator said. “In what sense can we guarantee students a feeling of safety? What does safety mean? We are going to have free expression facilitators. We won’t bring in police. We’re going to try and model civil discourse.”

That’s a relief. I asked where discourse around the war sat on the priority list for university leaders right now. The answer was somewhat surprising: Yes, it’s a focus, they told me, but competing for attention with immigration proposals that could curb international student visas; tax policies that would affect endowments; and the Supreme Court ruling that outlawed affirmative action in admissions.

Protests blocking the president’s office or the library, this official explained, “are noisier and less existential.” Trump’s immigration policies, on the other hand, could block up to 40% of science graduate students and researchers, they said.

“A university administrator distinguishes between problems that affect the current group and problems that affect the long term,” they explained. “Their job is to think about problems that affect the long term. The world can only look at problems that affect the current group. So there feels to be a major mismatch.”

I asked if universities were worried about Jewish alumni who said they would no longer give to their alma maters. Short answer: No; there are always donors withdrawing and others engaging. As for whether protesters’ demands for divestment, “non-starter,” they said.

“Some universities are doing procedurally what they would do with any request, which is sending it to their committees,” the administrator explained. “But they are doing that because they don’t want to do a desk rejection. Nobody’s sending it to their committees with the expectation that it will be endorsed. It just doesn’t fit in the principles.”

I asked this official what their main takeaways were from what was universally understood to have been a very bad year for universities.

One: “Don’t publicly say what you’re thinking!” This was in reference, mostly, to the presidents of Harvard and UPenn who lost their jobs after a congressional hearing in which they seemed to suggest that threatening Jews with genocide was not a clear violation of campus conduct codes.

Two: “Having informal lines of communication across the campus saved us, and the most important thing that any campus can do long before anything happens, is just create networks of conversation among the various groups.”

Three: Don’t be so quick to call the police. “One of my colleagues said, ‘It’s like you’re lying down, and our choices are ibuprofen or brain surgery.’ I think one of the things we learned is we don’t have any intermediate ways of dealing with things, and we need to build a lot of those, because most of what we face is neither ibuprofen nor brain surgery, but one of the million things in between.”

It’s worth noting that the problems this week were all quickly addressed by administrators. Cornell condemned the anti-Israel vandalism to its Day Hall; MIT’s Jewish president denounced the distribution of fliers promoting the antisemitic Mapping Project; and administrators at Michigan thwarted the student government’s refusal to fund clubs until the school divests from Israel by funding the clubs itself.

Back at Brown, one of our tour guides was a pre-med student from Los Angeles who does Shabbat dinners at Chabad, wore both a Star of David and a chai pendant on separate chains around his neck, and carried a water bottle with an Israel sticker. An Israeli-American mom wearing a hostage dog-tag asked him afterward about the climate on campus.

“I love being Jewish at Brown,” he said. “It’s a huge, huge part of my identity here.”

He said Hillel had paid for a group of students to travel to Washington, D.C., for the pro-Israel rally last fall, and that they’d had a table on the quad supporting the hostages. Also that the community had split over the war — he is active in Brown Students for Israel, but Brown Jews for Ceasefire galvanized a lot of his peers. He noted that Brown’s president, Christina Paxson, is a convert to Judaism, and said she had “been a bridge” between groups.

“I’ve never felt unsafe,” he told us. “There’s definitely times I’ve been uncomfortable.”

As the fall semester begins, students, administrators, parents and Jewish organizations need to remember the difference between those two things. And to carry ibuprofen — or something stronger.