Everyone thought I was crazy for majoring in religious studies. Here’s why it matters now more than ever.

‘After growing up in D.C., during the rise of the evangelical right, the topic felt too important to ignore’

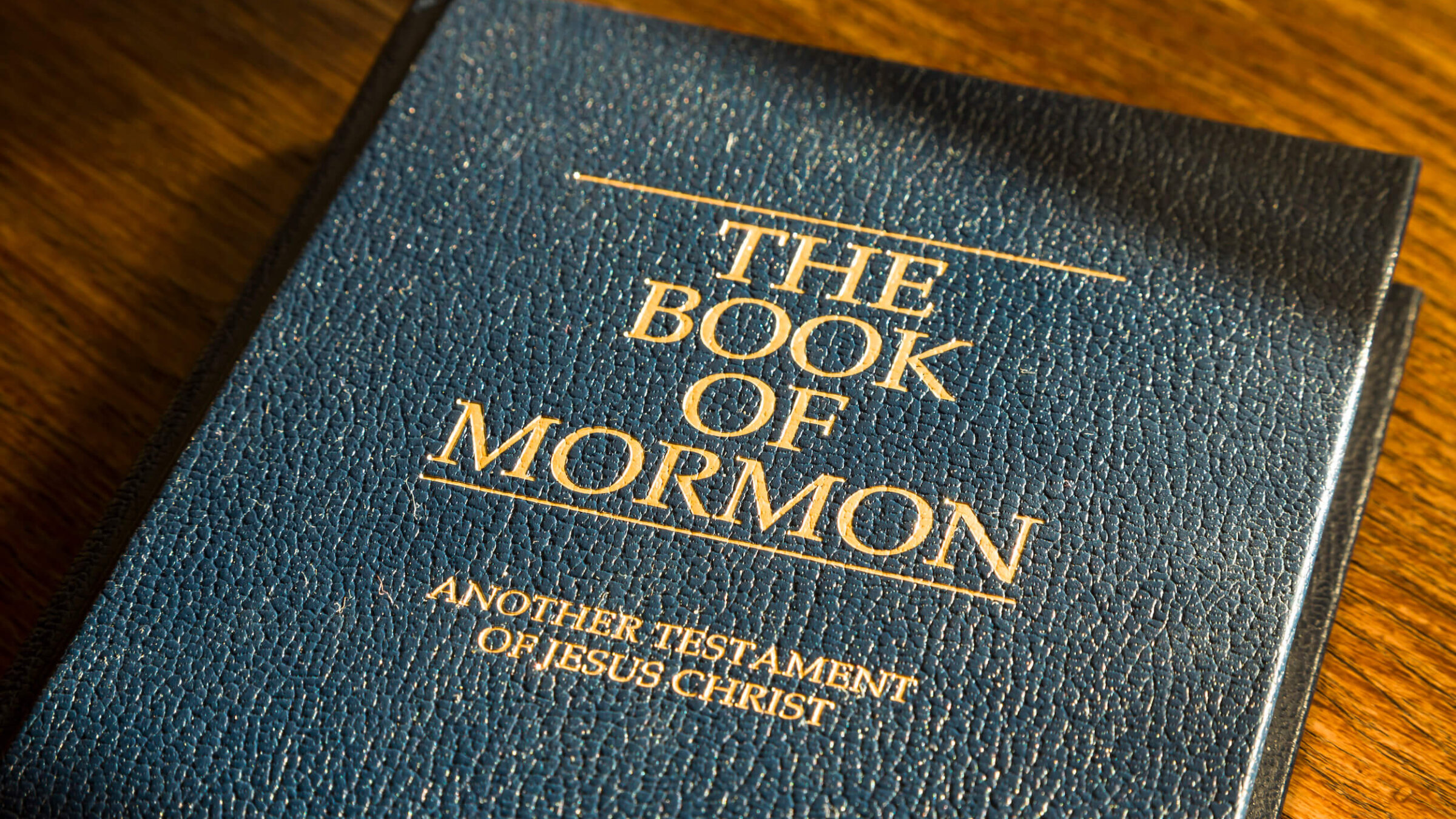

Utah, USA – May 23, 2012. The Book of Mormon, Latter Day Saints bible in English Photo by Paul Maguire/iStock by Getty Images

One year, for Hanukkah, my grandmother gave me the Book of Mormon.

She was not trying to convert me. She was not a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. She was Jewish, though a deeply secular Jew who found joy in trying to introduce her more observant friends to the pleasures of shrimp cocktail.

Instead, what she was trying to do — either humorously or passive-aggressively, depending on whom you ask — was drive home a criticism of my college major: religious studies.

I was not trying to become a rabbi or other pastoral professional, which confused everyone — though I’m not sure any member of my family would have been any more enthused about me joining the clergy. My grandmother seemed to think my choice in liberal arts degree was going to turn me into some kind of fanatical zealot. A family friend repeatedly urged me to consider going into chemical engineering, a subject I had never displayed any interest in or aptitude for. My parents tried, desperately, to convince me to take some classes in, well, anything else.

“I remember telling you that you should add philosophy to be more employable,” my mom recalled when I called her this week to rehash her reaction. “And I remember thinking: There aren’t a lot of parents telling their children to major in philosophy to be more employable.” (I did do a minor in philosophy.)

I forged onwards, nevertheless; after growing up in D.C., during the rise of the evangelical right, the topic felt too important to ignore. Eventually, I even got a master’s in religion.

But now, religious studies is in danger of disappearing. The humanities, in general, have been facing criticism for at least a decade, and over the past few years, dozens of universities have cut majors like English, sociology and art. The University of Oregon announced cuts this week that eliminate at least 60 jobs, and may entirely erase several departments, though the Judaic studies department — which was originally slated for elimination — gained a last-minute reprieve after professional associations and at least one major donor weighed in.

Religious studies has found itself particularly in the crosshairs of these cuts, not because it is so esoteric or irrelevant to modern life — in fact, the classes are usually well-enrolled and the professors popular — but because it is so closely connected.

Trump has sharply criticized universities for a wide array of ills, particularly spreading antisemitism. It’s hard not to believe that university leadership is targeting religious studies departments in an attempt to align the university more closely with the Trump administration’s priorities, which has nearly completely eradicated federal funding for the humanities. The Trump administration even specifically named my alma mater, Harvard Divinity School, as responsible for Harvard’s “antisemitism” and “ideological capture,” and the Religion, Conflict, Peace program was suspended for its focus on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

But blaming religious studies departments for antisemitism is a deep misunderstanding. In fact, these classes are where many students come for the first time to think critically about religion’s role in society, outside of whatever faith or culture in which they may have been raised. Religion departments also usually house universities’ Jewish studies departments and Holocaust studies programs; it is hard to imagine fighting antisemitism at universities without any courses about, well, Jewish history and antisemitism.

Religious studies classes are where Christian students might learn nuanced history that defangs the idea that Jews killed Jesus. Or they might become more critical consumers of media after a course on Nazi rhetoric during the Holocaust, allowing them to see and ignore antisemitic rhetoric or conspiracy theories they encounter online. They might simply take a course on Hasidic thought or Talmudic interpretation or — why not — Jewish food traditions, any of which might help them find beauty in Jewish culture that they would never have otherwise encountered.

In short, religious studies is essential to fighting antisemitism, not to causing it. And anyone concerned about antisemitism on campus should realize that removing classes about Judaism will only make it harder for students to understand the problem.

As for the more practical, job-related concerns, those might be fair — but students with all kinds of practical-sounding majors can end up with jobs in unrelated fields. And people with impractical-sounding majors can end up with jobs in exactly what they studied. I did, after all.

I never did read the Book of Mormon, though.