How Alvin Ailey’s ‘Revelations’ evokes Yom Kippur for me

Is it ridiculous for me, a Jew, to start crying during “Fix Me, Jesus?” I don’t think so.

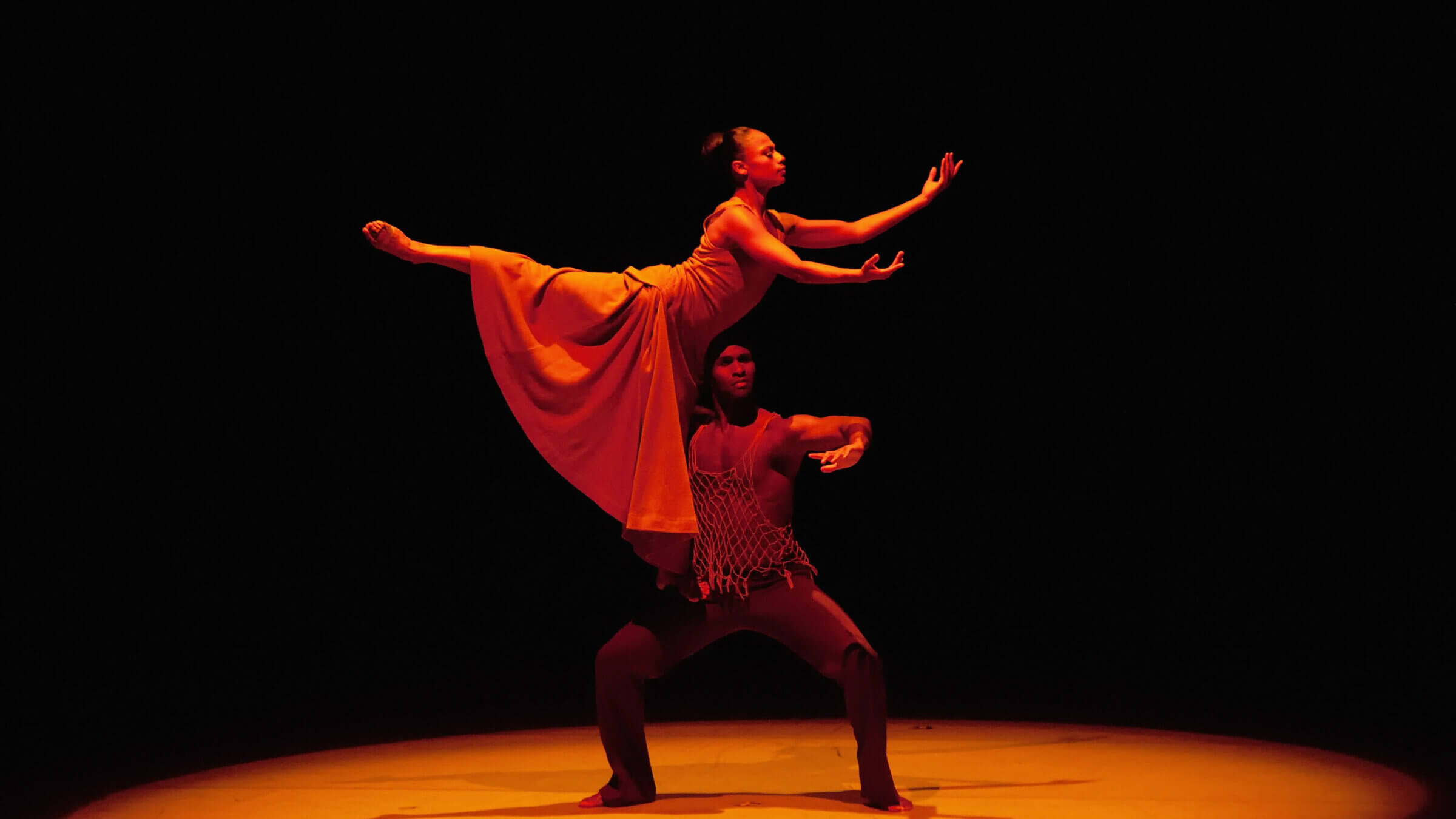

Dancers Linda Celeste Sims and Glenn Allen Sims perform in the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater production of “Fix Me, Jesus” at the Segerstrom Center For The Arts on Mar. 6, 2012. Photo by Doug Gifford/Getty Images

My last semester of college, I had an Alvin Ailey phase.

My time in Philadelphia was rapidly coming to a close and I felt an urge to make it to as many of the performing arts venues in the city as I could (not an easy feat). With a close family friend, I attended my first Alvin Ailey performance at the Forrest Theatre. Soon after, I went to a talk at the African American Museum in Philadelphia about Ailey and the piece The River. That weekend, I also watched the 2021 documentary Ailey. Then I found myself doing a sociolinguistical analysis of Ailey’s most famous work, Revelations, for a class.

To call my interest in Ailey a phase is actually a misnomer since, two years later, I am still an Ailey fan — and now the owner of an actual Alvin Ailey-branded hand fan. Last June, I attended a performance during their run at the Brooklyn Academy of Music and fell in love with Grace, choreographed by Ronald K. Brown. I bought a ticket to see it again, along with Revelations and two shorter works, during their winter season at New York City Center.

While the end of Grace — in which a dozen dancers take a nearly 30-minute-long journey to a promised land — made me tear up, it wasn’t until Revelations that I actually began to cry. It happened during the duet “Fix Me, Jesus,” in which a female dancer searches for spiritual guidance and a male figure depicts divine support.

I was aware of the irony. As a lifelong Jew, I have never wanted Jesus to “fix” me. But the piece moved me to tears nonetheless. Within the gospel music, New Testament themes and African American cultural imagery of Revelations — composed of multiple smaller pieces — is a universal story of desire for redemption and turning to faith in times of great suffering.

The choir that accompanies the dance sings “fix me for my long white robe,” a reference to Revelation 6:11, where those that have lived their life without sin are told they will be given white robes for their ascension to Heaven. I was reminded of the kittel, a plain white robe some in the Ashkenazi tradition wear on Yom Kippur. Some rabbis have interpreted the robe to symbolize the blank slate we are creating for ourselves in the new year. Dressing plainly can also be another way of resisting earthly pleasures on the Day of Atonement. Since some people are also buried in their kittel, another interpretation is that wearing it helps one consider their death and what legacy they want to leave behind, thinking of how they may “fix” themselves to be ready for when they will be brought before G-d.

These echoes of Yom Kippur make another appearance in Ailey’s Revelations in the solo “I Wanna Be Ready.” The single dancer dressed in white alternates between contracting and expanding their body, kneeling and prostrating on the ground, as if they are repenting for something. The choir chants that they want to be ready to put on their long white robes and the lead singer explains he has avoided the temptation to sin so his soul will be ready for death.

This deviates slightly from how I think of preparing for the Day of Judgment. For me, Yom Kippur has always been about acknowledging that we will sin, that we are human, flawed, prone to jealousy and gossip and all those other things we list as we beat our chests during the confessional. In the Reconstructionist Press version of the Prayerbook for the Days of Awe, Rabbi Rami M. Shapiro writes that “we freely admit our failings” in order to “create our atonements.” In the confessional, we are instructed not to tell G-d that “we are righteous, and we have not sinned,” for “indeed we have sinned.”

I have always experienced Yom Kippur as an intense emotional journey to find within myself the ability to do better, be better, perhaps with some divine guidance. This is what I recognized in “Fix Me, Jesus,” this burning desire to exceed our own expectations.

But the yearning of Revelations is not just about individual spiritual reckoning. Throughout the work, you can feel Black Americans pushing toward freedom as they emerge from the degradation of slavery and Jim Crow.

I connect with this existential cultural aspiration to escape systemic degradation both as a Black American and as a Jewish American, descended from enslaved people on one side and pogrom survivors on the other. Although Revelations originated in a specific cultural context — born from Ailey’s experiences growing up in the Black church in 1930s Texas — its broader message about redemption feels unifying across cultural divides. I have imagined seeing Revelations with my paternal grandmother, an active and dedicated member of the Black Presbyterian church. Even if we were to appreciate the dance’s spirituality for different reasons — her for the work’s reflection of her faith in Jesus, me for its raw portrayal of an intense desire to improve — it’s something that would move both of us.

Probably my tears were triggered by the intensity of the piece and the beauty of its dancers and not by some spiritual awakening. Still, despite — or really, because of — the emotional unrest Alvin Ailey put me through, they will probably be seeing me again soon.