The 2000s: Dashed Hopes, New Hopes

SEPARATION: Sharon turned the security fence into reality.

The most recent decade in Israel’s existence, 1998 to 2008, started with great expectations and ended on a note of sobriety and soul-searching.

SEPARATION: Sharon turned the security fence into reality.

There were great expectations for peace after Ehud Barak won a landslide victory in 1999 to become Israel’s prime minister: expectations for a stable, efficient government, for better schools, for greater social justice for Jewish and Arab citizens — in short, for a better, brighter Israeli society.

Ten years, four governments, one intifada and a full-scale war later, peace is still elusive, government reform remains an unfulfilled promise and Israel’s social gap is one of the widest in the Western world.

The Barak years were characterized by new momentum toward peace, but they ended in fiasco. Ever the strategic thinker, Barak wanted to reach a permanent-status agreement with the Palestinians sooner and faster than anyone thought possible. Ambitious and impatient, he decided to abandon phased agreements and interim arrangements and seek a full, comprehensive, final agreement.

In the beginning of 2000, Barak resumed negotiations with Syria, but these collapsed three months later. In May 2000, one year after taking office, he fulfilled a campaign promise by withdrawing the army from Lebanon to the internationally recognized border. It was taken as proof that withdrawing from occupied territory could enhance Israeli security, even without the other side’s cooperation. Unilateralism was born.

On the Palestinian front, Barak’s strategic goal was to reach a final end to the long conflict. At Camp David in July 2000, at a summit he had pressed hard to convene, he offered Yasser Arafat a Palestinian state and broad compromises on Jerusalem and the refugees. Arafat did not agree, and the summit broke down. The result was an end to the Oslo process and an outbreak of unprecedented violence that became known as the second intifada.

In the closing days of 2000, as the violence raged, President Clinton tried to save the talks by putting forward his own proposals, the Clinton Parameters. But they came too late. The violence had swept away whatever trust remained between the sides.

Thus, the year 2001 ushered in a new era. Two new leaders, President Bush and Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, would shape our lives in this region in the years to come. Both men were reluctant to continue what they considered failed American and Israeli policies. Both were focused narrowly on security; both dismissed talk of reconciliation.

That fall, on September 11, American thinking came to a historic turning point. For the next five years, the peace process was hardly considered seriously as an option.

A series of American mediation missions were launched — Mitchell, Tenet, Zinni — but each ended without concrete results. Violence continued unabated. Israelis wielded the power of the strong, the Palestinians used the power of the weak, daily casualties were high, but no one seriously tried to stop the bloodletting.

By late 2002, Israel had lost all faith in Arafat as a negotiating partner. Washington forced him to name a prime minister to manage the anarchic Palestinian security apparatus. In the spring of 2003, under intense American prodding, the mild-mannered Mahmoud Abbas took the job. A hudna, or truce, was promptly declared. Israelis enjoyed their first summer of calm in three years. But Abbas was weak, and little was done by Israel or America to shore up his authority. Sharon had lost faith in the Palestinian Authority. As for President Bush, he had decided that the road to Middle East peace passed through Baghdad.

In June 2002, amid growing American-European tension over Bush’s Iraq policy, the president appeared on the White House lawn and delivered a Middle East policy speech, calling for the first time for a Palestinian state. He outlined a series of steps leading up to statehood. The plan came to be known as the “road map” to Palestinian statehood.

Sharon accepted it with no great enthusiasm. He cited 14 itemized misgivings about the plan. In the end, though, the plan was never taken seriously. Time and again, the eternal question of implementation before any plan can be acted on is “Who will do what first?”

Moreover, the “no partner” argument becomes the leading theme all along the decade; it is the raison d’etre for any refusal, for every postponement, the final blow to any possibility to move forward. It serves as a firm basis for Sharon’s no-negotiations strategy

Consequently, public debate in Israel moves between four options: an attempt to reach a comprehensive solution, past failures notwithstanding; the possibility to move toward a partial agreement (stage 2 in the Road Map); unilateral steps precluding any agreement with the Palestinians, and, last but not least, a continuation of the status quo, in the hope that deadlock would bring about the ultimate demise of the Palestinian national movement.

The first option inspired two important nongovernmental initiatives, draft peace outlines known as the Ayalon-Nusseibeh “six-points plan” and the Geneva Initiative. Both documents sought to demonstrate that solutions exist and that an agreement is, in fact, possible. Both offered guidelines for any future agreement.

Sharon’s policies, however, wavered between the three last options. He publicly embraced the Road Map and announced a plan for unilateral withdrawal from Gaza. At the same time, he expanded and deepened settlement activity.

The pendulum swung dramatically in another direction when Sharon went one step further and formally accepted the principle of Palestinian statehood. A taboo was broken when the man known as the father of the settlements, a living symbol of the Greater Israel policy, declared that occupation must end.

It is within this context that one should view another factor that changed the geopolitical map of Israel: the security fence. Originally termed the “separation fence,” it was promoted from 2001 onward by advocates of unilateral separation from the Palestinians, in order to bring about a normalization of life in Israel. It first met with opposition from right-wing circles, Sharon included, because of fears that it might mark a final border — and leave settlers on the wrong side. But as acts of terrorism grew in number and intensity, public opinion demanded the fence’s erection, and the Sharon government turned it into reality.

Sharon’s transformation was complete — as he decided on and carried out the total pullout and evacuation from Gaza. Demography and security were good arguments to use, but the signal was clear: This was the end of the settlements policy. And that did not fail to bring about a transformation of the political map in Israel: a breakdown of the Likud; the creation of a new party, Kadima, and a deep crisis in the settlement movement.

One cannot attempt to sum up a period filled with wars, terrorism and violence without mentioning its effects on the Israeli society: a tremendous increase in fear, trauma and violence, including domestic violence; a dramatic impoverishment of vast segments of the population; a significant decline in social justice. Today, 1.5 million Israelis, a fourth of our population, live in dire poverty. One out of every four Israelis cannot make ends meet.

Poverty is especially present among new immigrants, Arab citizens of Israel and the elderly, including Holocaust survivors. About 40% of those who live under the poverty line are employed, and yet they cannot provide their families’ basic needs. While globalization, the world financial crisis, the wars and terrorism can account for much of this situation, there is no doubt that the neo-liberal policies of Benjamin Netanyahu as finance minister have been a determining factor. The measures adopted, including incentives for the wealthy and dramatic cuts in allocations for the elderly, children and single mothers, have hit hard on the weaker elements of our society. It is true that, thanks partly to budget cuts, Israel’s economy has been strengthened and is considered one of the most stable economies in the Western world. But this has been achieved at the expense of those who are destitute, and this in turn threatens the social fabric of our society. Numerous are those who understand nowadays that Israel’s security and survival depend not only on the performance of its defense forces but also on social cohesion and solidarity.

The 2006 Lebanon war had its own far-reaching impact on the Israeli psyche, on its self-image. As they did after the Yom Kippur war, Israelis had come to question hitherto axiomatic truths — about the invincibility of their army, about the limits of force, about their sense of security and above all, about the conduct of their government and the trustworthiness of politicians. Military thinking and military doctrine had to be adjusted accordingly. A more logical, professional process of decision-making is being put in place with the long-delayed empowerment of the National Security Council. In the social sphere, a variety of measures are taking shape to reduce poverty, while popular support is growing for an initiative, led by the Histadrut labor federation and the Manufacturers’ Association, to create a Social Security Council.

Paradoxically, it is 2006’s Lebanon war — unplanned, unprepared, its success still being questioned — that has brought about an Israeli strategic turnaround. Its leaders now realize that the neighborhood has changed. They understand that Israel and the moderate Arab states face a common threat from Iran’s aggressive policies and goals. Extremist Islamic movements such as Hezbollah and Hamas threaten not only Israel but also the Palestinian Authority and nearby Arab regimes.

With old troubles still fresh and new ones looming, the Saudi peace initiative, first adopted in 2002 by the Arab League and dismissed out of hand by Israel, has become an attractive option. It becomes evident that there has been a quiet sea change in the Arab world, most of which is now ready to recognize and accept Israel in its midst.

As Israel’s sixth decade draws near its end, serious messages are being exchanged between Syria and Israel, heralding a renewal of negotiations. After three earlier rounds of talks, both parties fully understand the price of peace. For Israel, however, gains could be larger this time. Peace with Syria could considerably diminish Iran’s margin of maneuver in Lebanon and elsewhere. It would curtail the capabilities of Hezbollah and other terrorist organizations and could influence trends in Gaza.

Israel’s prime minister, Ehud Olmert, seems to have discovered what all his predecessors, left and right, found out once they took office: that peace with Syria and the Palestinians is a necessity for Israel, and it entails a price that must be paid for Israel’s own sake.

At the end of the decade, the traditional disagreements between left and right have lost much of their relevance, as a majority of Israelis support the end of occupation and the creation of a Palestinian state. Moreover, the debate on the path to follow seems to be over, too. Unilateralism is largely discredited as an option. Our negotiating partner is our partner, however imperfect. Israelis may be less hopeful than they were, but they are more realistic in their demands. They know the limits of military power. What’s more, they know that time is running out. It may just be that sense of urgency that will make an agreement possible at the end of 2008.

Colette Avital is a Knesset member representing the Labor Party. A former diplomat, she headed the Knesset’s investigative commission on Holocaust assets and now chairs the committee on immigration, absorption and Diaspora affairs.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

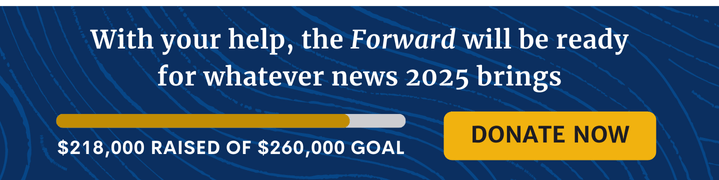

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO