Daniel Bell, 91, a Leading American Intellectual Who Eschewed Simplistic Labels

Asked as a young man what he specialized in, Daniel Bell, a member of the second generation of New York intellectuals who came bursting out of City College in the 1930s blurted out, “I specialize in generalizations!” It was said with youthful intellectual exuberance at first, and then wryly repeated as the years wore on and his social theorizing grew in richness and audacity.

Bell, who died on January 25, aged 91, was one of America’s leading postwar intellectuals. Born in 1919, the son of poor Jewish immigrants, he was as enduringly proud of having begun his professional life as a “pusher” of clothes racks in New York City’s garment district as he was of having ended up a professor at major American universities as an adult.

Despite battling over political and social ideas throughout his life, Bell was a born conciliator, loath to quarrel with friends. He was so well known for making peace after an argument by extending a dinner invitation that some were tempted to pick a fight with an eye only toward the meal!

Bell despised simplistic labels and recoiled from them, insisting on his right to heterodoxies and seeming contradictions. Hence his famous description of himself as “a socialist in economics, a liberal in politics and a cultural conservative.”

In his rich and long life, Bell was many things: journalist, intellectual, social theorist and, not least, a proud Jew, a man whose first language was Yiddish and who continued to dream in that language for many years. Though he ceased believing in God when he turned to politics as a young man, he soon came back to the wisdom of his Jewish heritage and to the inescapable pull of communal continuity.

“I write as one… who has not faith but memory,” he explained. “I was born in galut [exile] and I accept — now gladly — the double burden and the double pleasure of my self-consciousness, the outward life of an American and the inward secret of the Jew.”

This preceding quotation is from “Reflections on Jewish Identity,” written in 1961. In just 10 years’ time, Bell’s strong inner identity, like that of the entire American Jewish community, would grow more open and self-confident in its public assertion.

A sociologist by trade, a social critic by inclination, the former Harvard University professor was perhaps, best known for his often misunderstood proclamation at the beginning of the 1960s of “The End of Ideology,” his book propounding that grand ideological alternatives to democratic capitalism were no longer plausible. He followed this hypothesis with his widely influential theory of “post-industrial” society throughout the 1970s. Both theses have stood the test of time.

These were the highlights of a career spanning some 70 years that also included books on American socialism and education reform, and his searching as well as thoughtful look at what he termed “The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism.”

Above and beyond these specific achievements, Bell had an omnivorous mind. From the moment he began his intellectual life in the Young People’s Socialist League at the age of 13, he greedily (his word) gobbled the written world around him. It was not long before he became a polymath.

Bell, who began his career as a journalist at The New Leader and later Fortune, had a mind capable of ferreting out the myriad complexities in the facts of the world around him. His essays are full of detail and nuance and ambiguity, richly overstuffed with quotations, footnotes and references. This sensibility, this drive to force theory to face fact, was grounded in the harsh realities of 20th-century politics.

His early taste of Marxism also gave him the ambition to see the larger patterns at work in the world. But, like fellow New York intellectuals, Bell was a disillusioned Marxist utopian. His pride was that his own reckoning with Marxism came precociously early. After his conversion to socialism, Bell, like other young radicals, flirted with becoming a communist. Horrified relatives — anarchists who reviled the Russian system — schooled him in the perfidious history of the early Soviet government, specifically in the story of the 1921 Kronstadt rebellion, the insurrection of revolutionary sailors brutally put down by the young Soviet government. The inconvenient fact of those sailors’ deaths at the hands of a “people’s” government quickly put the lie to the Soviets’ utopian theories. Over the years, Kronstadt itself became a metaphor for disillusion. Every ex-communist had his Kronstadt. Bell boasted, “My Kronstadt was Kronstadt.”

And so, as a mature public intellectual, he cherished the skeptical attitude toward political absolutes and abstractions that he believed lay at the very heart of liberal politics.

A rigorous thinker, one who had been trained in pilpul both Jewish and Marxist, Bell understood the importance of “making distinctions.” In doing so, through the course of his long, productive life, he tirelessly sought, and provided, answers to the mysteries of the world around him.

Joseph Dorman is a documentarist whose “Arguing the World” (1998) showed the New York intellectuals and their world. He has just completed the film “Sholem Aleichem: Laughing in the Darkness,” which will have its theatrical premiere later this year.

Contact Joseph Dorman at [email protected]

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

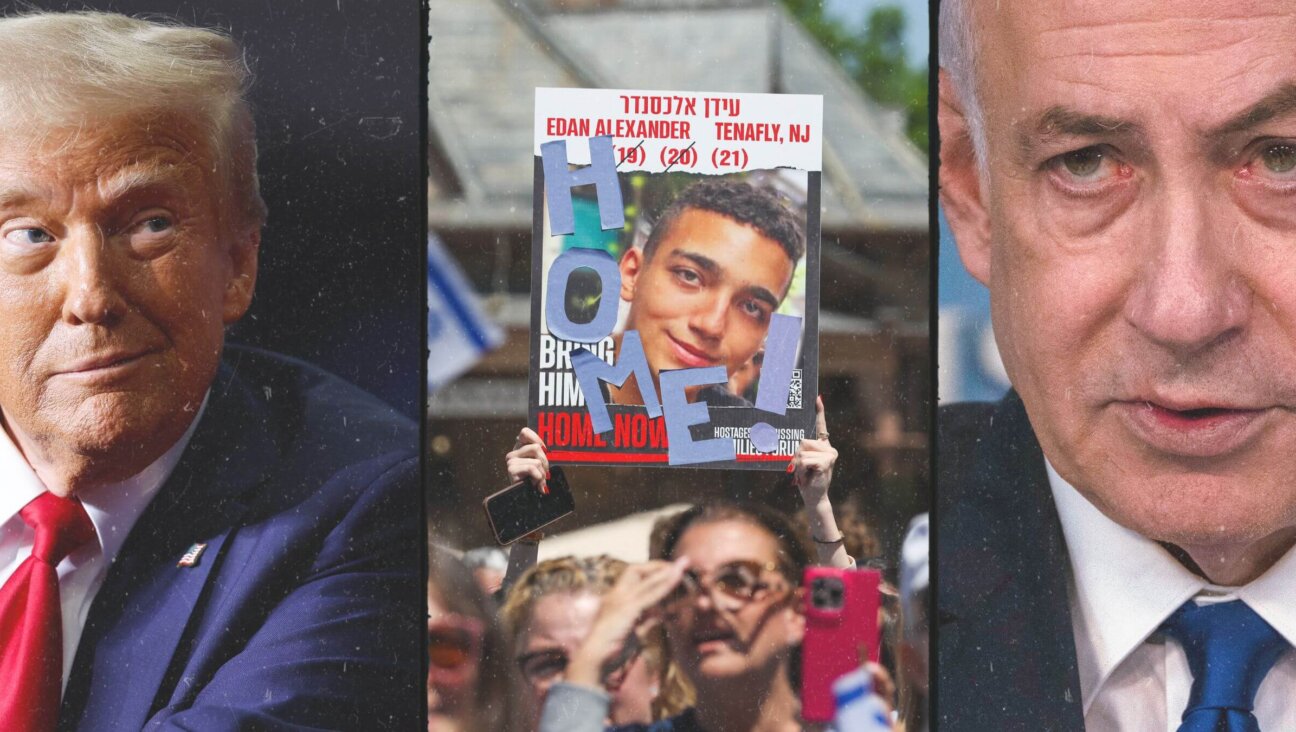

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Opinion Despite Netanyahu, Edan Alexander is finally free

-

Opinion A judge just released another pro-Palestinian activist. Here’s why that’s good for the Jews

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.