Doing It by the Book

Deuteronomy is often singled out as the book of the Torah that cares most about social institutions. It is the only one that contains legislation concerning kings and prophets — both found in this week’s portion, Shoftim. A careful look at these texts suggests that this legislation is trying to curb the power of these individuals.

Deuteronomy 17:14 suggests that it is the people, not God, who desire “a king… as do all the nations about” them, but God must elect this king. That monarch will be most unroyal; unlike the typical ancient Near Eastern ruler, he may not have too many wives, too many horses, or too much silver and gold (verses 16-17). Finally, “he shall have a copy of this Teaching (torah) written for him… and let him read in it all his life, so that he may learn to revere the Lord his God, to observe faithfully every word of this Teaching (torah) as well as these laws” (verses 18-19). The purpose of this teaching is “so he may not raise himself above his kin.” A king who is like all other Israelites is scarcely a king at all!

Prophetic power is restrained in a different manner. Deuteronomy 18:18 suggests that each generation has only one true prophet: “I will raise up a prophet for them from among their own people, like yourself: I will put My words in his mouth and he will speak to them all that I command him.” This corresponds to Deuteronomy’s depiction of Joshua as the single successor of Moses and of the succession of Elijah by his disciple Elisha. As usually interpreted, Deuteronomy 18:22 contains a very stringent test for distinguishing the true prophet from the false: False prophets are those whose oracles remain unfulfilled, and they are subject to capital punishment. Jeremiah 28:16 narrates the death of Hananiah, such a false prophet, in fulfillment of this idea from Shoftim: “I am going to banish you from off the earth. This year you shall die….” Thus, according to Deuteronomy, one thinking he or she heard a divine voice should wonder: Am I the one true prophet that God has established, making all the others speaking in God’s name charlatans? And what if it was just a weird dream, and it won’t be validated — given the penalty of error, is it worth claiming to speak in God’s name? And what if (as in the Book of Jonah) the people change their behavior, and the prophecy of doom is averted?

Prophecy and kingship may destabilize the torah. Prophets may claim to hear oracles that disagree with torah legislation, and kings, following ancient Near Eastern practice, might promulgate legislation that overrules the torah. Devarim, more than any other book of the Torah, is concerned with the torah and its maintenance (although it is not clear that torah in Devarim means Torah in our sense of the Five Books of Moses). It is Deuteronomy 4:44 — vezot hatorah asher sam Moshe…., “this is the Torah/teaching which Moses placed before Israel…” — that is recited when the Torah is lifted up during synagogue services. Devarim uses the word torah more than any other book in the Torah. It is the most book-conscious and torah-conscious section of the Torah, and therefore limits the power of king and prophet alike, so that nothing may usurp the power of the authoritative written word. After all, last week we read (Deuteronomy 13:1), “neither add to it nor take away from it,” suggesting an immutable, unchangeable torah book.

There are certain ironies in this notion. First of all, Devarim cites laws and stories found in previous books, but changes them. Furthermore, the language of Deuteronomy is often laconic and unclear, and it often begs for interpretation, including innovative interpretations that will change the simple sense of the text. Thus, the very book that encourages conservatism by giving primary power only to the word, and by emasculating prophets and kings, also encourages creativity and liberalism, for, after all, there is no single and obvious way to “do it by the book.”

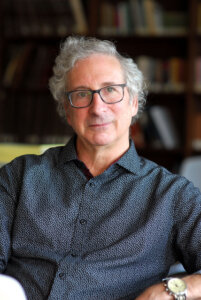

Marc Zvi Brettler is Dora Golding professor of biblical studies in the department of Near Eastern and Judaic studies at Brandeis University. He was co-editor (with Adele Berlin) of “The Jewish Study Bible,” which was awarded a National Jewish Book Award, and the author of “How To Read the Bible,” published in 2005 by the Jewish Publication Society.