New York State’s Oldest Landsmanschaften Celebrates 100th Anniversary

Roots of a Family Tree: The Cantor Family Society was founded in 1913 by Israel Aaron Kantrowitz. Image by Johnna Kaplan

When Mikhail Kivovich came to America from Belorussia in 1991, he knew he had relatives who had arrived here many decades earlier. But until he attended the recent reunion of the Israel Cantor Family Society, he had no idea how many. Or how far back they went.

It was the print-out of the family tree that stretched horizontally across a long wall in a large room at the Isabella Freedman Jewish Retreat Center in the Connecticut Berkshires that stunned him. The family’s earliest member in America dated back to 1778.

“I almost cried,” said Kivovich, who is now a programmer in Chicago. He described meeting with his extended family as “one of my best moments in America.”

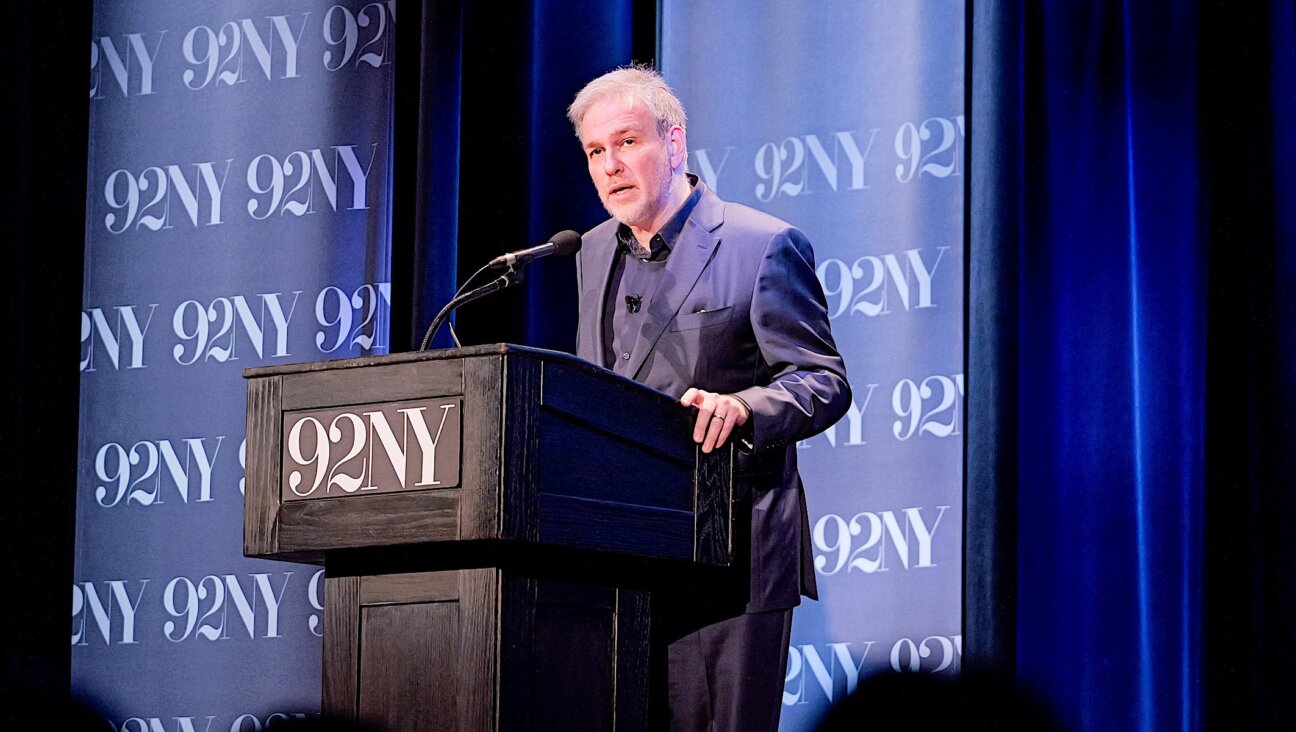

At the society’s 100th anniversary meeting, held August 23 to August 25, Kivovich was far from alone. Dan Cantor, the executive director of New York’s Working Families Party, could be seen at one point walking about the retreat grounds with four young members of the extended Cantor clan trailing behind him like confident, intelligent ducklings as he talked about how rare it was in America not only to know your 5th cousins, but to actually like them.

Founded in 1913 by Israel Aaron Cantor (Kantrowitz before he immigrated from Minsk), the Israel Cantor Family Society today numbers around 100 members, 64 of whom attended the 100th anniversary meeting. The society claims to be one of the oldest still-active landsmanschaften, or immigrant benevolent associations, in New York State.

Jewish immigrants to America formed landsmanschaften as burial or mutual aid societies. Membership was based on shtetl of origin, political ideology, or, in the case of the Israel Cantor Family Society, familial ties. Landsmanshaften dispatched much-needed aid to Europe during World War I, then mostly declined despite a short revival in the immediate aftermath of World War II. But the Israel Cantor Family Society is still thriving. It holds regular meetings twice a year, and larger gatherings every five years. The group’s main business function is maintaining plots in two cemeteries in New York and New Jersey. But it also operates as an unusually regulated, recurring family reunion.

The 100th Anniversary celebration’s oldest attendee, Florence Hornick, is 89. She remembers her parents taking her along to Society meetings, which were once held monthly, at New York’s Broadway Central Hotel. “We used to run up and down the steps as children,” she said.

Hornick’s maternal grandfather was Shmerel Cantor, one of the society’s founders. After a failed attempt to organize the group in 1905, he and his co-founders succeeded eight years later “at my father’s bris,” said Dan Cantor. In the early years of the Society, meetings and minutes were in Yiddish, dues made up a significant percentage of a member’s income, and anyone joining after the age of 30 had to have a physical to prove he wasn’t signing up for the death benefits.

Family Ties: Generations of Cantors attended the reunion. At 89, Florence Hornick was the oldest among them. Image by Johnna Kaplan

Today, membership dues are about $20 per year for a single member and $40 for a family. The money funds burials and meetings, as well as donations to members in need. Florence Hornick’s son Sandy, former deputy executive director for strategic planning at New York City’s Department of City Planning, recounted a particularly dramatic instance of this sort of aid: a family member trapped in Germany in 1939 wrote to the Society for help. Members sent money, and at the last minute he was allowed to leave.

Whether the younger generation will preserve the current structure of the Society remains to be seen. “You can’t force them,” Dan Cantor said.

One of those younger members, 22-year-old Tess Liebersohn, who grew up in Philadelphia and works at a summer camp in California, said she had always associated the Society with the family’s older generations. But she added, “It is kind of cool to have this community that’s entirely based on history.” Liebersohn, a Cantor on her mother’s side, said her friends were “completely confused” that her family reunions involve a constitution and bylaws. “They think it’s crazy we have to pay to be in this family.”

But for now, the younger members seem engaged. They were “sitting on the edge of their seat” listening to the story of the Kivovich family’s immigration from Belorussia, Dan Cantor recalled.

At Isabella Freedman, a historic camp-like getaway in the Falls Village section of the town of Canaan, Conn., family members from as far away as Los Angeles and Denver mingled with others from New York, New Jersey and New England. Many Cantor descendants only see each other at such meetings. Libby Cantor Paglione made the trip from Wyoming, where she moved “to be in the mountains,” she said, after hiking the Appalachian Trail about six years ago.

Libby’s father John Paglione is Italian-American and one of the Society’s Social Members, a classification developed for non-Jewish spouses. Social Members can’t vote on bylaws or cemetery-related matters, but they are otherwise welcomed into the group. This wasn’t always the case; one family member’s marriage to a Cuban in 1947 caused a rift in the clan. Jewish spouses are given automatic full membership with voting rights, and all children have to be proposed for membership when they turn 21, though, Dan Cantor said, “It’s always unanimous.”

John Paglione, who lives with his wife Barbara Cantor in Ann Arbor, Mich., was not put off by large, boisterous gatherings of Cantors. “I’m from an Italian family so we have a big extended family too,” he said. The Society meetings are “just more organized.”

They are also diverse. Aside from the differences in geography, the group represents a range of political and religious attitudes. According to Dan Cantor, they don’t spend much time talking about potentially thorny issues.

Tess Liebersohn “love[s] that there are so many different kinds of Jews in the same family,” but added that if the topic of Israel ever came up, the conversation could quickly become divisive. “The only Israel we talk about,” she says, “is Israel Cantor.”

The importance of lineage and of the immigrant story, in both its 19th century and more recent incarnations, are recurring themes among Society members. “What I think is extraordinary,” said Sandy Hornick, “is we can trace our family back to 1778. George Washington was fighting the American Revolution when the oldest guy on that family tree… was born.” Tess Liebersohn echoed this thought when she spoke of “understanding… the family’s place in America.” They were not “Mayflower people,” she says, but “I know exactly where they came from.”

Contact Johnna Kaplan at [email protected]