From the archive, 1959: Passover in Castro’s Cuba, yearning for freedom

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

In the very first edition of the Forverts newspaper, published during Passover 1897, Cuba made headlines. “Bravo Kubaners,” read our story in support of an independent Cuba, freed of Spanish rule.

A century or so later, as we celebrate Pesach 2020, Ben Weitz figured it was the perfect time to tell the tale of his Cuban grandfather, Azriel, who was born the same year as the Forverts, lived in Cuba for most of his 84 years, and never abandoned his Jewish faith despite all the challenges he confronted.

And what a story it is, with its overtones of exodus and deprivation and resilience, best exemplified, perhaps, by Azriel Weitz’s decision to write to the Forward from Havana not long after Fidel Castro took power in January, 1959.

“My dad would tell me his story like this,” Ben Weitz began in a recent interview. “Castro took power and the revolution rolled into Havana. So, it was either 1959 or the following Pesach that the state began taking hold of things — stealing the businesses immediately, and people took flight. Rationing began and shelves in stores were empty. And there went the supplies for Pesach.”

Ben Weitz is 45, lives in Atlanta with his wife and two daughters and works as a corporate trainer. He and his sister were born in the United States, their parents having married here after leaving Cuba. But Azriel, the patriarch, remained behind. And “every Pesach,” Weitz recalled, “my father would remind us of our grandfather.”

Listening to Weitz tell his family’s story, it’s easy enough to imagine Cubans who did not want to live under Communism gathering, in effect, at the edge of the Red Sea, seeking freedom. And to recall that for many of the island’s 15,000 Jews, who were fearful for both their religion and their family’s livelihoods under Castro, leaving was not realistic.

“Not everyone had the means to leave,” Ben Weitz noted. And for his grandfather, an immigrant from Lithuania and synagogue regular, there was no way Passover could happen without proper Pesach products. “Ultimately, there was an appeal made,” Ben Weitz said. “My grandfather wrote to the Forverts, looking for supplies.”

Whether the Forward was able to help is unclear. But Ben Weitz’s brief, unleavened story of his grandfather’s life in Cuba is not designed to answer every question. How could it?

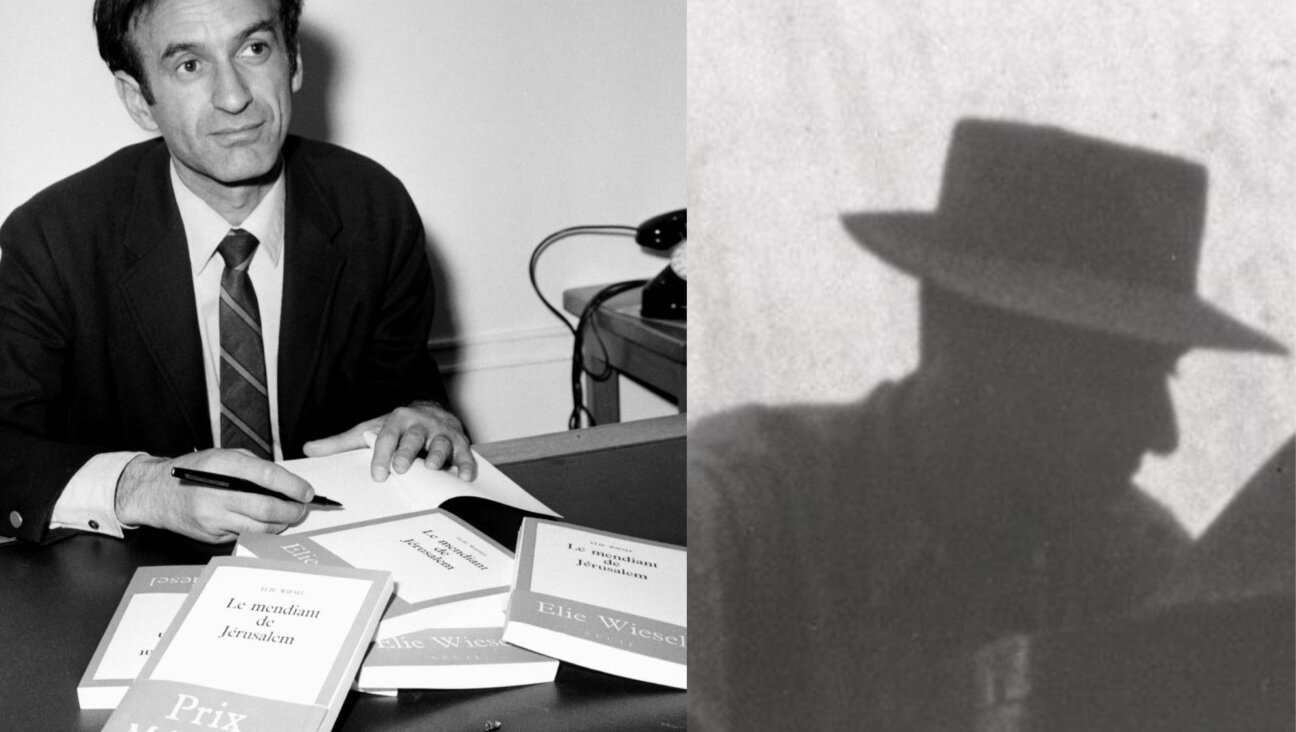

Ben Weitz in Atlanta, Georgia, April 2020, holding the one image the family has of their grandfather, Azriel Weitz of Havana. Photo: Sarah Weitz

“We don’t have a lot of artifacts from Cuba,” he said. “Maybe a few pictures people managed to take out. And so, Pesach is a bit more poignant because of that piece of memory recalled. And there is this one image that managed to get to us, of my grandfather, who was a gabbai at the Adath Israel synagogue in Cuba.”

In this one, spare photograph, Azriel Weitz is posed in his tallit and tefillin. Ben Weitz thinks his family obtained the picture from an American sports team that was permitted to travel to Cuba and, like many visitors, stopped at the Havana synagogue. Grateful for his ability to have a synagogue to attend, Azriel was said to warn tourists against talking politics with him, saying: less talking, more davening.

It was a message that captured the ambiguity of Jewish life in Cuba after Castro’s revolutionary government took power. At first, religious practice was strongly discouraged, but the restrictions were eased in the early 1990’s. More recently, there has even been a little bit of a Jewish renaissance; in 2014, the Forward organized a tour there. And all along, Jews like Azriel Weitz, who died in 1981, truly kept the faith.

B’chol dor v’dor, we recite from the haggadah. Every generation is obligated to recite the story of our exodus. Like so many children of immigrants, Ben Weitz tried, too, to have his parents recite theirs.

“My grandparents emigrated from Eastern Europe to Havana way before World War II,” Weitz said. Ben’s father, Sam, his grandparents’ only child, traveled from Cuba when he was young to study at Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin Coney Island, before eventually returning one last time to Cuba and then settling in Passaic, N.J.

This was all long before Castro overthrew the dictator Fulgencio Batista and took power. In the early 1950s, Sam Weitz signed up to serve in the Korean War, and after he returned, found work in a factory, where he remained employed to the end of his career.

Those are some of the basic facts, along with Sam’s marriage to Lydia, another Cuban refugee, though she came years later, in the 1960s, through a lottery. Ultimately, Ben said, his father seemed to shield other parts of his own story with determined silence — except for the annual retelling of Azriel Weitz’s letter to the Forverts seeking help.

“He was kind of a trauma-based introvert,” Ben said of his father, “so I wasn’t able to have him tell me his whole story. Ever.”

He did learn that there was “a young cousin of my father’s who was sent here as part of America’s Operation Peter Pan,” which resettled unaccompanied minors from Cuba. “He was shipped over, adopted and raised here by a separate family,” Weitz said. “Those are the kinds of efforts people were making to get off the island.”

Now, in this year’s Passover of solitude, with many Jews in self-exile from family members, Ben still feels grateful when he compares what we are dealing with to the environment his grandparents endured in Cuba. “My grandparents, and the rest of Cuba’s remaining Jews, were alone. Very alone.”

So alone, in a sense, that it was only recently that someone representing the Weitz family was able to visit his grandparents’ graves: an American rabbi who is a friend of Ben’s.

“When I hear people speak of being alone for Pesach during the coronavirus, for the first time — I think of the families that never rebounded after the Holocaust,” Ben Weitz said. “My own family went through similar privations and a subsequent loss of family. We were literally just smashed.”

This year in Atlanta, Weitz said, he feels grateful for the Passover supplies he does have and for the company of his wife and two daughters.

“We’re doing what we can,” he said on the eve of the first Seder. “We have a box of matzah, we’ve got our mezuzahs on our doors, we’ve got wine and we’ll have as good a seder as we can, _baruch Hashem.”

“At the end, we’ll open the door for Eliyahu,” he said. “I imagine that’s what my grandfather did.“

Do you have a story of how the Forward made an impact on your family? Send it to [email protected]

Chana Pollack is The Forward’s archivist.