A Showdown in Ann Arbor: Behind the New Lawsuit Challenging Longtime Synagogue Protesters

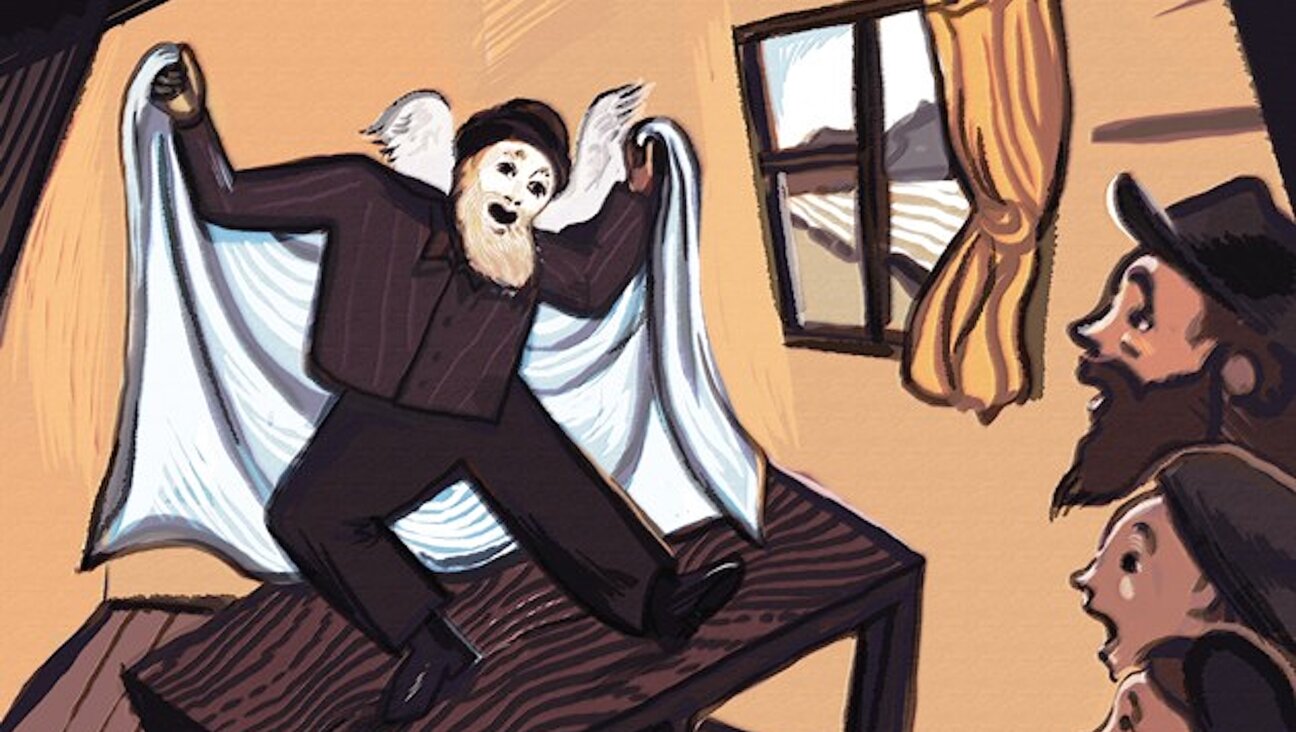

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

It’s a brutally cold Saturday morning in February, and Dearborn resident Chris Mark is one of only two people from a group called Witness for Peace standing outside Ann Arbor’s Beth Israel Congregation.

The group used to be bigger, but Mark said many members have passed away over the years, and it’s hard to bring out people in the winter. This week, even the group’s leader and founder, Henry Herskovitz, is on vacation in Florida.

Mark stands on the farther side of Washtenaw Road with signs opposing the Israeli occupation of Palestine, as well as a concept the group calls “Jewish power.”

In the synagogue parking lot, arriving congregants pay no attention. On Washtenaw, cars speed past Mark and the group’s other member that day, but drivers mostly ignore the protests, too. After all, they’ve taken place every Saturday morning since 2003, as congregants file into Shabbat services.

Two months from now, not even the COVID-19 outbreak will stop Witness for Peace. Some members will continue to protest outside Beth Israel, even after the synagogue has shut its physical doors.

For now, well before the pandemic is on anyone’s mind, cars speed past Mark and the group’s other member. Drivers mostly ignore the pickets, but some will flash Mark a thumbs-up, or a middle finger.

One man slows down as he passes through the intersection and raises his middle finger. Mark yells out at him.

“Thank you! Love you! Love your dog!” Mark screams. “He gets me every week. Always gotta give me the finger. He has a really nice chocolate lab, though, really sweet.”

This has been the scene outside Beth Israel for more than 16 years. But now something is different. Now, Witness for Peace is at the center of a lawsuit challenging the distinction between lawful protest and impeding religious freedom.

Free Assembly or Hate?

Herskovitz, an Ann Arbor resident who says he formerly identified as Jewish, started protesting outside Beth Israel after returning from a trip to Israel over 16 years ago.

In 2003, he founded a group called Jewish Witnesses for Peace and Friends for the purpose of organizing the protests. About three years ago, Herskovitz changed the group name to Witness for Peace.

Witness for Peace sign outside Beth Israel Congregation in Ann Arbor Image by (Alex Sherman)

But Canton-based attorney Marc Susselman told the Jewish News he first found out about the protests in the spring of 2019, when his friend Henry Brysk sent him an article about them.

Susselman did some legal research, which led him to believe the protesters’ actions were not protected by the First Amendment. So on Dec. 19, 2019, after finding a Beth Israel member named Marvin Gerber willing to be a plaintiff, Susselman filed a complaint against the protesters in the U.S. Eastern District Court.

Brysk’s wife Miriam Brysk, a Holocaust survivor, also joined the suit as a plaintiff on Jan. 2, 2020. The synagogue itself has decided not to participate in the suit.

The suit argues that Herskovitz’s group violates the First Amendment by impeding congregants’ right to practice their religion and compelling them to see the protests even if they don’t want to. The complaint also lists several Ann Arbor city officials, including Mayor Christopher Taylor, contending that the protests violate city code but that officials have neglected to enforce their rules.

The plaintiffs are asking that the court either stop the protesters altogether or place restrictions on their conduct. They’re also seeking damages.

Outside organizations have gotten involved on both sides. On Feb. 24, The Lawfare Project, a New York-based legal network that works to defend the Jewish and pro-Israel community, joined the lawsuit as a co-counsel and to provide financial assistance. Then, on March 17, the Michigan chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union filed a brief on behalf of the defendants, arguing that Witness for Peace’s actions are indeed protected under the First Amendment.

“The offensive, distressing, and even outrageous nature of their demonstration cannot justify any of the relief the plaintiffs seek here,” the ACLU brief says, citing several landmark free-speech cases.

But the Lawfare Project believes the nature of the group’s protest moves the case out of the realm of free speech.

“The protesters’ attempt to use the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to impede the religious practice of the worshippers at Beth Israel Congregation, by staging aggressive protests outside what is permissible by city code, and with anti-Semitic signs such as ‘Jewish Power Corrupts’ and ‘Resist Jewish Power,’ is unacceptable,” Zipora Reich, director of litigation at the Lawfare Project, told the JN.

“Unlike our ancestors who had no legal recourse to stop anti-Semitism, we live in a country with constitutional protections. The Lawfare Project believes that it is incumbent upon the Jewish community to avail itself of those protections.”

The lawsuit is undergoing preliminary legal steps in court, and Susselman said he hopes to determine whether Ann Arbor city code prohibits parts of the protesters’ activity.

“If we prevail on those motions—and we are cautiously optimistic that we will prevail—there will be a trial to determine if the protesters and the city have been violating the plaintiffs’ constitutional and civil rights over the last 16½ years,” Susselman said. He suspects that trial would occur this fall or in early 2021.

On March 26, the defendants’ attorneys filed a motion to dismiss the case.

Roots in Hate

Beyond the signs themselves, there are several other links between Witness for Peace and anti-Semitism.

Herskovitz is a former board member of Deir Yassin Remembered, an organization founded in memory of the 1948 massacre of Palestinians in Deir Yassin, a village near Jerusalem. In 2017, the Southern Poverty Law Center declared Deir Yassin Remembered a hate group under the category of Holocaust denial, although an SPLC spokesperson said the group’s Ann Arbor chapter has since been removed from their list due to inactivity.

Herskovitz was removed from the organization’s board after a new director took over earlier this year. But he’s written blogs praising neo-Nazis like Ernst Zündel, who was imprisoned in both Germany and Canada for speech inciting racial hatred before his death in 2017, as well as white supremacist Richard Spencer.

Herskovitz said members of the Ann Arbor city council have previously called him a Holocaust denier. For his part, he calls himself “a Holocaust revisionist.”

The Anti-Defamation League has tagged Witness for Peace as anti-Semitic. Herskovitz insists they’re a “love group.”

“We love our country and we love the Palestinians,” Herskovitz told the JN. “We hate what Jews are doing in the Jewish state… but we don’t hate [Jews].”

But to Nadav Caine, Beth Israel’s rabbi, the protests are clearly anti-Semitic.

“It’s really not about Palestinian human rights. And I think that’s a shame,” Caine said. “I wish it were… It is really about the ‘fact’ that Israel and the Jews control the world and it’s all those anti-Semitic tropes about [how] we control the banking, we control the American government, control the military.”

“Would You Like To See Us Shot?”

Caine came to Beth Israel from Poway, Calif., where he was the rabbi at the town’s Conservative synagogue. He knew about Witness for Peace’s activities when he took the job at Beth Israel, and it didn’t affect his decision. In fact, Caine said anti-Semitism is around whether people realize it or not, and he felt it was important to stand with Jews experiencing it.

Since arriving at Beth Israel, he’s kept up the synagogue’s existing policy of not engaging with the protesters. But Caine said he did go up to Mark and the other protesters once, on the Saturday after the April 2019 shooting at the Chabad of Poway.

“After the Poway shooting, as I’m walking by, I turned to one of the protesters on the next Saturday morning and I said, ‘I just have a question for you — would you like to see us shot?’” Caine recalled. “And he turned to me and he said, ‘Well, it would be an appropriate response considering the Israelis kill Palestinian children every day.’”

Mark acknowledged to the JN that the conversation happened, but denied that he gave Caine that response.

Caine said he does think the repeated protests have affected Beth Israel and its congregants. Like many synagogues around the world, Beth Israel has security measures in place. While Caine said he’s pro-security, it also makes it difficult to do certain activities and offer services.

“It makes it virtually impossible to do things like host homeless people or give sanctuary to refugees,” he said. “I just can’t open the door and have people come in and out like they might do at a church, and those kinds of things do sadden me.”

He thinks it’s possible the protests have discouraged some people from coming to synagogue or joining the congregation.

”Rabbi

“I suspect that many people get used to it, even though I know some never do. But I can tell clearly that when people are coming for the first or second time, they’re showing up for a bar mitzvah or showing up for a baby naming, it’s horrifying,” Caine said. “I suspect it’s probable that people have said, ‘That’s not a place I really want to go back to for that reason.’”

The City’s Response

Caine said he hasn’t felt much support from the Ann Arbor city government.

“I would like to see Beth Israel form a more constructive and positive relationship with the city of Ann Arbor,” he said. “I have reached out to people in the city government, and my experience has been that they feel very resigned to the fact that this is clearly all perfectly a part of free speech.”

The city’s involvement — or rather, its lack thereof — has become a central part of the lawsuit. Susselman believes the protesters’ actions violate Ann Arbor City Code. He contends they should be required to apply for permits for their protests, and that city officials have been ignoring the regulation.

Ann Arbor Mayor Christopher Taylor said he couldn’t comment on the lawsuit or on Ann Arbor’s specific permitting guidelines, but he told the JN he found the protests “disgraceful and deeply misguided.”

Despite his personal feelings, though, Taylor said he and other government officials don’t have the right to restrict the protesters’ speech.

“The sidewalk is public space, and people in America have a right to occupy public space and to protest on public space,” he said. “They have the right to say wise things and they have the right to say unwise things, things which are admirable and things which are loathsome.”

For Caine, though, it goes deeper than the mayor not taking legal action against the protesters. He feels many Ann Arborites see the protesters as advocating for Palestinian rights. He thought that, too, when he first moved to Ann Arbor.

“I took it as a typical sort of… progressive, if misguided, way of advocating for Palestinian human rights. But now I understand Henry Herskovitz better and understand the group better. And I think most people don’t,” he said.

Caine, who identifies politically as liberal, said he sees this as indicative of a larger problem: He feels progressive spaces no longer recognize the existence or severity of anti-Semitism.

“The one thing that struck me moving here is that when I visited here with my family the first time, one of the first things I noticed was the signs in people’s front yards that say, ‘No Place For Hate.’ And then once I moved here, I immediately saw that, you know, Ann Arbor is no place for hate — unless you’re a Jew. And that seems to be widely accepted,” he said.

According to Deborah Dash Moore, a Judaic Studies professor at the University of Michigan and a member of Ann Arbor’s Jewish community, anti-Semitism at its core assumes Jews are in positions of power, even when they aren’t.

“To see that Jews can be vulnerable despite holding positions of power is a kind of oxymoron” to some people, she said.

Much of the conversation surrounding anti-Semitism today revolves around how to separate it from legitimate critiques of the Israeli government.

“And can you distinguish [anti-Semitism] from saying that, you know, Israelis unlawfully occupy certain territories?” Moore said. “Yeah. You can distinguish that. Can you distinguish it from saying that Israelis have two legal systems in those occupied territories, one for Palestinians and one for Israelis? You can.”

During Michigan’s shelter-in-place ruling, Caine has moved Beth Israel services online. But the protests continue, their already small numbers not much impacted by the coronavirus.

Herskovitz is taking time off due to what he calls the “corona issue,” but said the remaining protesters are practicing social distancing by standing “at least 50 feet apart.” He said he also believes that continuing the protests helps prove the group is not motivated by hate.

“The presence of vigilers without the presence of congregants supports our contention that the target audience of our protests is the general public, and not Jewish individuals like Ms. Brysk and Mr. Gerber,” Herskovitz told JN in an email.

The group activities continue online, as well. In a blog post published April 4, Mark wrote about that week’s protest.

“We are the only group, maybe in the entire world, who has proven an essential need to exercise our Constitutional rights against the (((Masters of Chaos))), who will never rest until their boot has happily crushed the windpipe of the Gentiles,” Mark’s post reads, employing the triple parentheses commonly used as code for Jews on alt-right and neo-Nazi forums.

That cold day in February, Mark says he’s not sure how much longer the protests will go on.

“I’m the young gun, right?” he says. “I’m two decades below [the others].”

Mark is named as a defendant in the lawsuit along with four other protesters, and says he thinks the suit is “so frivolous and stupid.”

For Susselman and the plaintiffs, though, the suit is about standing up for themselves. “It is unacceptable for Jews to tolerate being harassed and insulted with respect to their religion and their support for the State of Israel as they approach their place of worship,” he said. “No religious segment of our society would tolerate such disparagement in proximity to their place of worship, and Jews should not tolerate it either.”

Regardless of the lawsuit’s outcome, once the older protesters can’t come anymore, “it’s gonna die,” Mark says. He doesn’t want to come to Beth Israel by himself, and it’s difficult to get new people to join.

When asked why, Mark says, “Jewish power, absolutely.”

This article first appeared in The Jewish News. Reprinted in collaboration with The Jewish News.