This is what democracy looks like

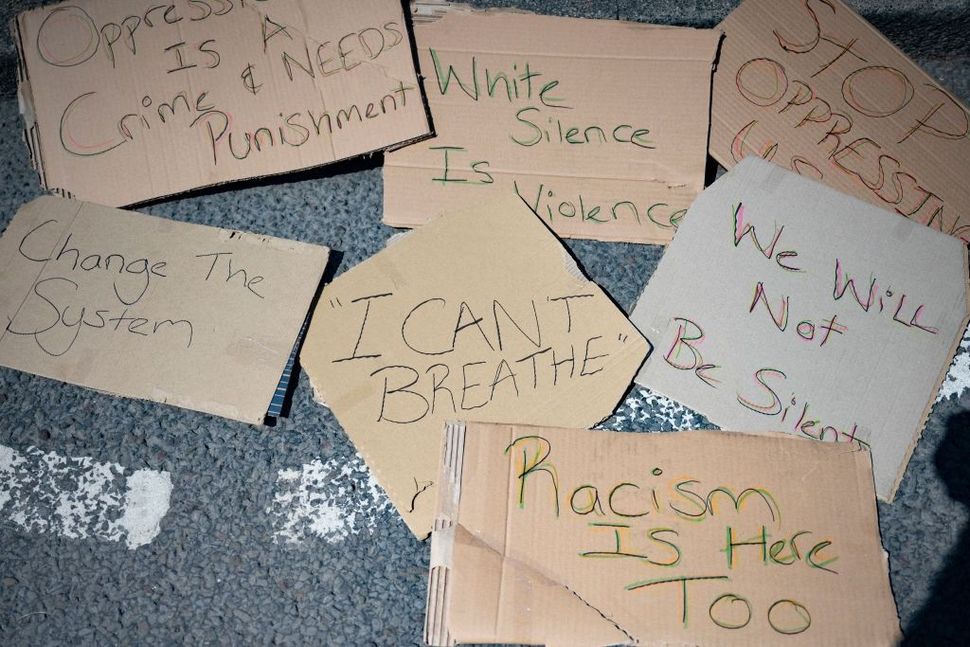

Signs from a protest litter the ground. Image by Matthew Horwood / Getty Images

When 17 students and teachers were gunned down in a school in Parkland, Fla., two years ago, it felt as if it had happened in our backyard. Our kids were only 6 and 7 at the time, but we quickly gave up on hiding what had happened: Parkland is like Greater Boca; there were kids in our school who had cousins or friends or babysitters who were now dead.

So when March for Our Lives organized protest marches around the nation a month later, we took the kids, who were then in kindergarten and first grade, to one in South Florida. After all, it was about them: kids have a right to go to school and not get shot there.

The author’s two children (right) at the 2018 March for Our Lives protest in West Palm Beach. Image by Ilene Prusher

“Show me what democracy looks like!” my kids, then in kindergarten and first grade, called out to the people marching with us.

“This is what democracy looks like!” the people chanted in response.

Though it was bittersweet to see the cocoon of their childhood crumble a bit, attending that march felt right from every perspective. We were making our voices heard, and we showed our children to stand up for what they believe in. We wanted them to know that talking and tweeting about it is not enough.

So why are we not out on the streets now? Is it any less outrageous to see a Black man’s life snuffed out under the knees of three white policemen?

For one thing, we’re scared. Many protests start out peaceful, but others turn violent in a heartbeat — violence sometimes fomented by protesters, and sometimes by the police. The things I might have done at 20 and 30 I will not do when I’m closing in on 50 and have two children to protect. Plus the real possibility of contracting the coronavirus. Wasn’t it yesterday that we were told that the last place any of us should put ourselves is in a crowd of hundreds of people?

But here’s the larger, painful truth: Too many of us aren’t sure where we’re supposed to be standing at this moment. We believe intrinsically that black lives matter — all lives matter — but many of us cannot bear the thought of buying a #BLM narrative that is wholly anti-police, knowing that without law enforcement we can trust, Jewish safety and survival in this country is tenuous.

There is also the 2016 Black Lives Matter statement that backed the Boycott Divestment and Sanctions movement against Israel and indicated that Israel was partaking in a “genocide” against the Palestinian people. Even my most liberal Jewish activist friends, in groups like T’ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights expressed extreme dismay over the platform. Anti-Semitism masked as anti-Zionism also crept into the Women’s March, which many of us proudly attended in January, 2017, and have stayed away from ever since.

During my 15 years living and working as a journalist in Israel, I developed a strong belief that the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territory and mistreatment of Palestinians is a core part of the problem — but not the only problem. Yet the BLM platform seemed to indicate that no part of Israel was legitimate, and only one side was to blame. (Interestingly, when I recently re-read coverage of that controversial 2016 platform, the links to the original document led to a dead end.)

What’s happening today across America is not about Israel or Jews, and I don’t want to turn it into that. But neither can I avoid it, because my own evolution as an advocate for justice leads through Israel and Palestine. I was on a few occasions mistaken for a Palestinian at Israeli checkpoints, and the sting of hearing a soldier brusquely shout “hawiyeh!” (ID card) at me has stayed with me.

On the one hand, I often enjoyed the privilege of passing: I look local in many parts of the world, and that meant I could blend in where other Western journalists did not. On the other, there was a price to pay. When on a trip back to the U.S. around 2004, after having been reporting in Afghanistan and Iraq, I kept being pulled aside from among long lines of white people at airports and being told that I was being “randomly selected” for additional screening. It was probably about where I had been, but the fact that I vaguely looked the part put me in the shoes of the racially profiled.

Since childhood, I’ve been described as “pretty brown,” “a bit swarthy,” looking Latino, Middle Eastern or Mediterranean, and even “so dark” — that is, for someone who, according to the census anyway, is part of white America. (Upon return from an Israel visit last summer, someone here commented that I looked “savage.”)

I can’t say that I know what it’s like to be Black, but I do know how it feels to be viewed with suspicion because of how you look, where you come from, or what group you belong to.

On a different trip to Israel, in my early 20s, I visited a dear old friend of my mother’s. They had been in the same idealistic “Habonim” movement together, except that the friend, Carol — now Shira — had moved to Israel and founded a kibbutz. We went through old photographs I had never seen before. My mother’s family and hers had been close — their fathers were lantzmen.

In one photo, the two men were at a May Day parade in New York City sometime in the late 1940s. Grandpa Charlie is holding a sign. It read, “Smash Jim Crow and Anti-Semitism.” A rush of pride ran through me. My grandfather, who died when I was an infant, a protester!

The author’s maternal grandparents, Charles and Fannie Weinstein, and her mother, Sandra, around the time Charles was involved in protests. Image by Courtesy of Ilene Prusher

Until that point, I knew that my grandfather had been a unionized furrier and an avid reader of the Forward. But I never knew that he’d been politically active in any way — or that he saw a link between the Jewish struggle and that of African Americans.

I didn’t get to keep the photo and Carol has since died, but I’ve found evidence that this was a common slogan among Jews of the period, who were protesting against both Crow-era poll-taxes — classic voter suppression — and rampant anti-Semitism coming from certain political candidates. Grandpa Charlie, it seems, could have made a good friend of Herman Levin in “The Plot Against America.”

I often think about this image of my grandfather. Why wasn’t this activism better known among the family? How much of a difference did it make? He, too, had a spouse and children at home. Was he scared that protests would turn violent — that police would respond with brutality? Was he marching and carrying his sign that day because he saw racial justice in America as something worth fighting for — worth getting arrested or injured for — or was it more of a strategic partnership between Jews and Blacks, people with overlapping yet different interests?

I’ll never have answers to many of those questions, but I find inspiration and a strange solace in my grandfather’s example. Engaging in the struggle to make the world a better place is in our blood. In fact, we’re commanded to do it. We might not finish the work, says a line in “Ethics of the Fathers,” but neither are we free from the obligation to spend our lives trying.

We come from a people who, according to a Truah T-shirt my Israeli-husband wears, have been “Resisting Tyrants Since Pharoah.” Many Jews played roles in the civil-rights struggles of the past, and we need to find ways to play meaningful roles in them now. We should not hesitate to protest against the heinous crime of police officers snuffing out a Black man’s life in broad daylight, or armed citizens gunning down a young man out for a neighborhood jog they viewed as suspicious.

I still feel a calling to take my children to stand up in a protest for George Floyd, the way we did over gun violence after Parkland. Instead, today as we watched the protesters on the screen kneeling in deference to his memory and in resistance to racism, we kneeled with them.

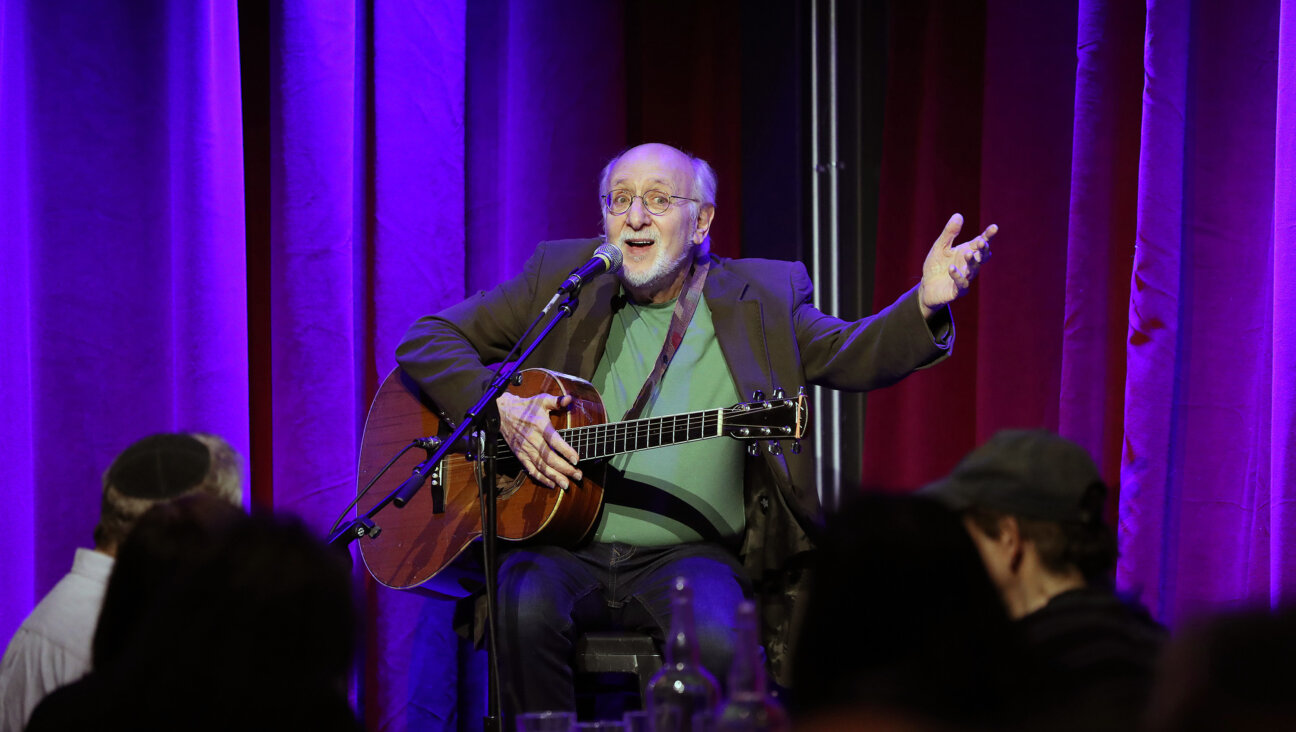

Ilene Prusher, a journalist in South Florida, is a regular contributor to the Forward and the author of the 2014 novel “Baghdad Fixer.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO