Israel’s Patron Deity

Most of the portion Ha’azinu comprises a long poem that is very schematic, emphasizing God’s great care for Israel, Israel’s rebellion, its punishment, and its ultimate rehabilitation. The language of the poem is more difficult than typical biblical poetry. Some scholars label it as “archaic” — that is, ancient — while others consider it to be “archaistic,” that is, pretending to be ancient. Dating such texts is beyond the ability of biblical scholarship, but its possible early date may explain why it is so hard to understand: We lack many other such early texts, and thus it is difficult to contextualize this poem; and the earlier a text is, the more likely that it has changed both accidentally and intentionally over time, making it much harder to uncover its original words and their meaning.

There are several places where the current text of Ha’azinu just doesn’t make sense. Verse 8 is the best known of these. The Hebrew would literally translate as: “When the Most High gave nations their allotments, when He separated humanity [literally, “the children of Adam”], He established the boundaries of peoples according to the number of the Israelites [literally, “the children of Israel”].” What could this mean? How are the nations’ boundaries connected to the number of Israelites? The number of Israelites at what point? And given that the Bible recognizes that the Israelites were latecomers to the Near East, after most of the other Near Eastern peoples had settled, how might we understand this comparison? Furthermore, the following verse reads: “For the portion of the Lord is His nation; Jacob is the share of His possession”; how is this connected to the idea of God establishing national boundaries according to the number of Israelites?

This is one of the clearest cases in the Bible where the standard Hebrew biblical text, what we call the Masoretic Text, is in error, and better readings have been preserved in other sources. Not only that, but we also can explain the current text as reflecting a theological “correction” of an early notion that later scribes found offensive or problematic.

Instead of “the Israelites [literally, “the children of Israel”],” Hebrew bnai yisra’el, a Dead Sea Scroll fragment reads bnai ’elohim — literally, “the children of God.” This expression is used elsewhere to refer to angels or semi-divine beings, and is found, for example, in Job 1-2, where God rules over the divine council, bnai ha’elohim. The Greek translation of the Bible (the Septuagint) was begun in the third pre-Christian century from a version of the Hebrew that preceded the one that is now standard; and where our text reads “the Israelites,” it renders “angels/messengers of God.” It is thus likely that the Hebrew text from which the Greek was translated read bnai ’elohim or bnai ’el (a shorter form of ’elohim). An additional witness to this reading is found in the apocryphal book of Ben Sirah, a book that is canonical in the Catholic tradition though not in the Jewish tradition. Originally written in Hebrew in the second pre-Christian century, that is, before the biblical text fully stabilized, it sometimes offers important evidence of a shape of an early biblical text. Small parts of Ben Sirah have been found in the original Hebrew at Masada and in the Cairo Genizah, but even in the Greek translation by Ben Sirah’s grandson, preserved within the Church, indications of a different biblical text are sometimes visible. For example, Ben Sirah 17:17 reads: “Over every nation he places a ruler, but the Lord’s own portion is Israel” (translation from Patrick W. Skehan, “The Wisdom of Ben Sira,” Anchor Bible, p. 277) — this clearly reflects Deuteronomy 32:8-9, and “ruler” must reflect bnai ’el (ohim) rather than bnai yisra’el.

One missing piece of background explains this variant reading: According to an (early) rabbinic tradition, there are 70 angels who have power over the nations, which are also 70 in number. Though only preserved clearly in post-biblical texts, this tradition likely goes back to biblical times. The theological meaning of the well-attested variant text of Deuteronomy 32:8 is now clear: God has a direct relationship with Israel, His chosen people, but when it comes to the other nations, he delegates to the angels. At least in biblical theology, such angels or divine beings have no independent power, and need to “check out” decisions with God, who can veto or modify them (see Job 1-2). But Israel has no such intermediary — it is God’s, and not some angel’s, charge.

Both the Bible and post-biblical literature had a wide range of understanding of monotheism; the role of bnai ’el(ohim), who might be perceived as semi-deities, and the power of angels. It is thus easy to see why someone who wanted to limit their role and was copying this text removed them from it by adding three Hebrew letters, changing ’el to yisra’el. True, the resulting text was difficult to interpret, but at least it was less problematic theologically. And as a result, a text that expressed Israel’s chosenness by highlighting its direct, unmediated relationship with God was lost to those who read the Bible in Hebrew (but not in Greek). Now, however, especially after the recovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, we have a better understanding of this difficult verse in Ha’azinu, which expressed the singular relationship of God and Israel by contrasting it to the relationship with Israel’s patron deity, God to the nations, with their mediated access to the divine.

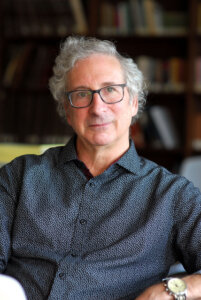

Marc Zvi Brettler is Dora Golding professor of biblical studies in the department of Near Eastern and Judaic studies at Brandeis University. He was a co-editor of “The Jewish Study Bible,” which was awarded a National Jewish Book Award, and the author of “How To Read the Bible,” recently published by the Jewish Publication Society.