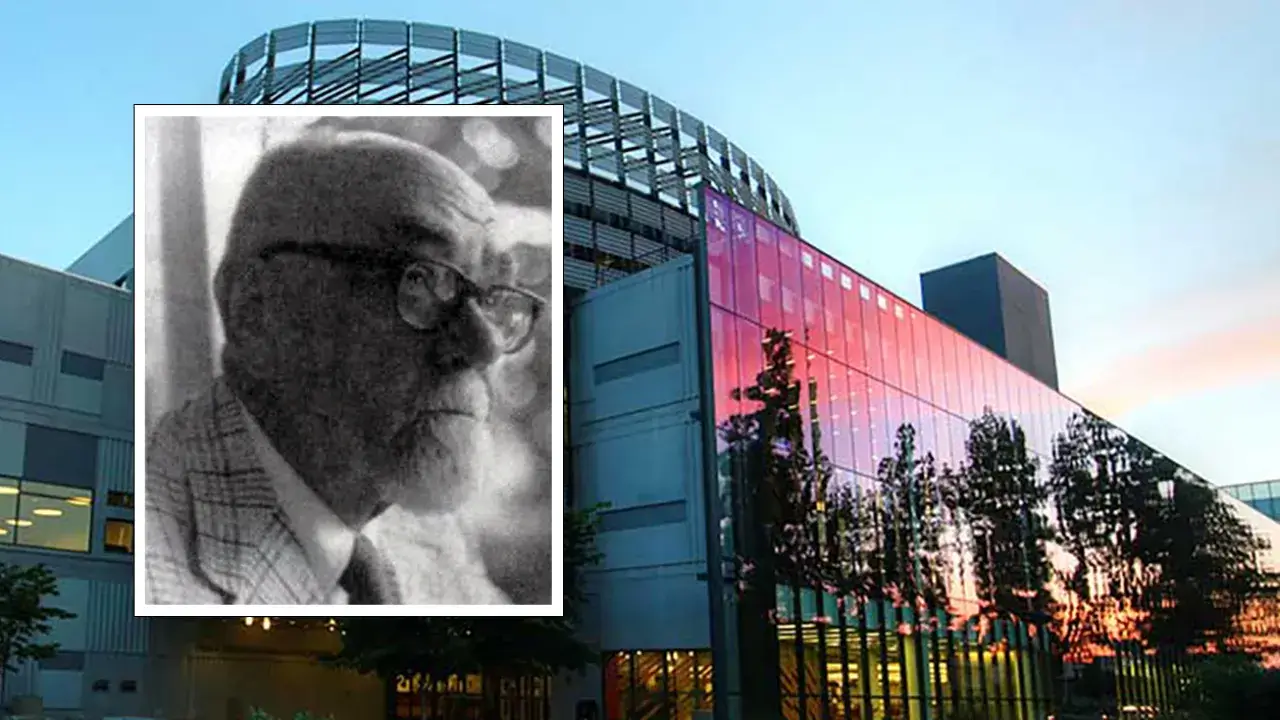

A beloved Fresno State librarian fantasized about ‘target practice’ on Jews

A new report sheds light on Henry Miller Madden’s Nazi views

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

A report commissioned by Fresno State University looking into the views of Henry Miller Madden, for whom the school’s library was named, has found copious — and unambiguous — examples of antisemitism, as well as a through line of heartfelt admiration for Hitler and the Nazi party.

“I think all of us were surprised by the extent, the virulence, of Madden’s antisemitism — and the persistence,” said Jill Fields, a history professor and founding coordinator of the school’s Jewish studies program, who was a member of the task force that created the report.

The report follows an announcement in December 2021 that administrators at Cal State Fresno would consider renaming the library. Bradley Hart, a professor in the school’s Media, Communications and Journalism Department, had included Madden’s writings in his 2018 book, “Hitler’s American Friends.” However, only after Hart mentioned this material during a lecture in November 2021 was there an outcry.

Subsequently, the school’s president, Saúl Jiménez-Sandoval, assembled a task force of academics, librarians and Jewish community members to look more fully into Madden’s papers — which are in the library’s collection — and examine his views over time in an effort to consider whether to remove Madden’s name from the library.

The results are damning.

Madden fantasized about driving Jewish people “barefoot to some remote spot in Texas … to find shelter under the bushes, closed in by electrically charged barbed wire, with imported SA [Nazi paramilitary] men stationed every ten yards apart, three men to each machine gun emplacement.

“Target practice will be permitted twice weekly,” Madden wrote, “with explosive bullets to be used on Yom Kippur, Rosh Hashanah, Purim, etc.”

“It’s so unapologetic,” said Hart, who served on the team that spent several months combing through Madden’s papers, a selection of which are available online.

Madden was born in 1912 in Oakland and became interested in German culture as a young man, although there is no evidence he had German ancestry. He studied history at Stanford and Columbia during the early 1930s, at which time he was already interested in the Nazi party, the report found.

“Where the Germanophilia comes from, and his pro-Nazi beliefs, is kind of puzzling,” Hart said.

The first instance of overt antisemitism expressed by Madden came in a 1934 letter to his mother written from New York.Where the Germanophilia comes from, and his pro-Nazi beliefs, is kind of puzzling.

“I spent a good 20 minutes walking, looking all the time for an honest gentile face, and I don’t think I saw one,” he wrote. “And such Jews! Noisy, dirty, smelly, ugly — Jews such as you have never seen before, absolutely different from S.F. Jews.”

A year later, he wrote in a letter to a friend his violent fantasy about herding Jews into a camp and killing them, beginning the passage with:

“The Jews: I am developing a violent and almost uncontrollable phobia against them. Whenever I see one of those predatory noses, or those roving and leering eyes, or those slobbering lips, or those flat feet, or those nasal and whiny voices I tremble with rage and hatred.”

Madden’s antisemitism seems to have developed in sync with his admiration for the Nazis, which only grew when in 1936 he made a tour of Europe and came away impressed with Hitler’s “New Germany.” After departing Berlin, he ended a letter to his mother with “Heil Hitler!”

It’s likely, Hart said, that Madden was aware his views were extreme. He toned down his rhetoric in 1937, when he became a lecturer at Stanford, where he taught a survey of Western civilization. However, he continued in private to support Hitler and wrote to the German government to obtain publications — state-sponsored propaganda — for his personal perusal but also to use as source material in his teaching. At the same time, his public lectures at Stanford were moderately critical of the Nazi party, while omitting or minimizing the ongoing brutality taking place in Germany. This was on purpose, Hart speculated.

Madden’s lectures are important, Hart said, because they reveal “he’s not showing a true version of what’s going on.”

They also make clear that Madden knew how to temper his rhetoric to avoid pushback from his contemporaries, Hart added.

That’s significant, according to Hart, because of criticism that Madden is being judged based on today’s values rather than allowing for historical context, given that antisemitism was rife at the time.

“Not true at all,” Hart said. “These are views that would have been appalling at the time. It’s not ‘cancel culture.’”

During the first years of the war, Madden supported neutrality while cheering German wins. But after the U.S. entered the war, attitudes toward Germany hardened and Madden’s letters stopped showing his support. His efforts to evade the draft as a conscientious objector were unsuccessful, and he spent 1942 to 1946 in the U.S. Navy, although not in combat.

“This is a man who as a Navy officer would have seen the footage of the camps,” Hart pointed out.

After the war, Madden returned to Europe with the International Refugee Organization to work on resettling displaced persons. In a 1949 letter to his mother, he complained that Jews had left the camp “in such condition that a self-respecting pig wouldn’t live in them.” He felt sorry for Germans displaced by the war, though: “The German refugees from Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia — they live in absolute misery.”

That same year, Madden became librarian at Fresno State University, a position he held for 30 years. In 1981, the library was named to honor him. A year later he died, and his papers were left to the library but sealed until 2007 (a request commonly made to protect people mentioned in papers while they are alive).

The report points out that, although he did not voice his full-throated antisemitism in his later years, Madden continued to use antisemitic language, and nothing in his writings indicates he changed his views about Jews.

“What surprised me was really his lack of reflection at any point,” Hart said.

Even months before his death, Madden mentioned in a letter how he’d helped a German, “probably a member of the SS,” to come to the U.S. He also, while at Fresno State, expressed casual racism about Mexican, Asian, Indian and Black people.

At the same time, colleagues saw him as a hardworking and respected professional who expanded the library by hundreds of thousands of volumes and was a champion in the fight against banning books in the 1950s and 1960s.

Hart pointed out that Madden personally went through his papers before donating them to the library, which meant he was aware he was leaving to posterity a curated record of his thoughts about Jews. Was it ego, an archivist’s desire for completeness or something else?

“We can only speculate about that,” Fields, head of Jewish studies at Fresno State, said. “But one thought is he hoped to be vindicated.”

To produce their report, researchers and scholars viewed more than 100,000 letters and documents in multiple languages. It was a large task, Hart said.

“It’s 53 boxes,” he said. “These things were densely packed.”

The task force released a preliminary report on April 18, and community forums have been held via Zoom to discuss the naming of the library, including one for the Jewish community on March 24 and an open forum on April 18. Another open forum is scheduled to take place this Friday, April 22.

In a comment appended to the report, Alea Droker, a Jewish studies minor at Fresno State and a student member of the task force, expressed support for removing Madden’s name from the library.

“The name that our library has represented for the last forty-one years is one that tarnishes the sense of belonging that Fresno State wishes to foster,” Droker said. “Changing the name of our university library is crucial if we want to continue to encourage our fellow Bulldogs, students and faculty alike, to engage with and strengthen Fresno State’s educational environment.”

Hart noted that the task force’s remit didn’t include recommendations about naming the Fresno State library, but that a final version of the report would be presented to school president Jiménez-Sandoval in May.

“This preliminary report is an exemplary testament to the cooperation and research by the task force and underscores the importance of transparency and accountability,” Jiménez-Sandoval said in an email. “I am incredibly grateful to members of our Jewish community, some of whom have served as members on this task force, and have provided meaningful, thoughtful and valuable feedback as we move forward.”

Jiménez-Sandoval is expected to make a recommendation to the school’s Board of Trustees this summer about the library’s name.

“We await the final outcome, but I anticipate the name will come off,” Fields said. “The evidence is overwhelming.”

Hart said that as the task force’s work wraps up, he and his colleagues are discussing how Madden’s career affected the school where he worked for so long and where his control of its library’s collections shaped scholarship.

“That’s something we’re actually talking about,” Hart said. “How did Madden’s own views influence what the campus became?”

This story originally appeared in Jweekly.com. Reposted with permission.