‘What began in L.A. blossomed years later’

Thirty years after the violent rebellion in Los Angeles, Rabbi John Rosove and Pastor Kenneth Flowers remember how their congregations came together

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Thirty years ago, I wrote the article pictured above for Fellowship, the magazine for the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the pacifist and interfaith social justice organization for which I was editor at the time.

I had been urged to come to Los Angeles in the immediate wake of the riots – or rebellion, as our organization and other progressives termed it – by the Rev. Glenn Smiley, a retired field secretary for the FOR.

Smiley already had a place in history as the white man sitting next to the Rev. Martin Luther King on the first interracial bus ride in Montgomery, Ala., in December 1956, and was now running a small nonviolence center in L.A. named for King. “Come here and be a journalist,” he told me. “You have to see it to understand it. Then you need to tell the story.”

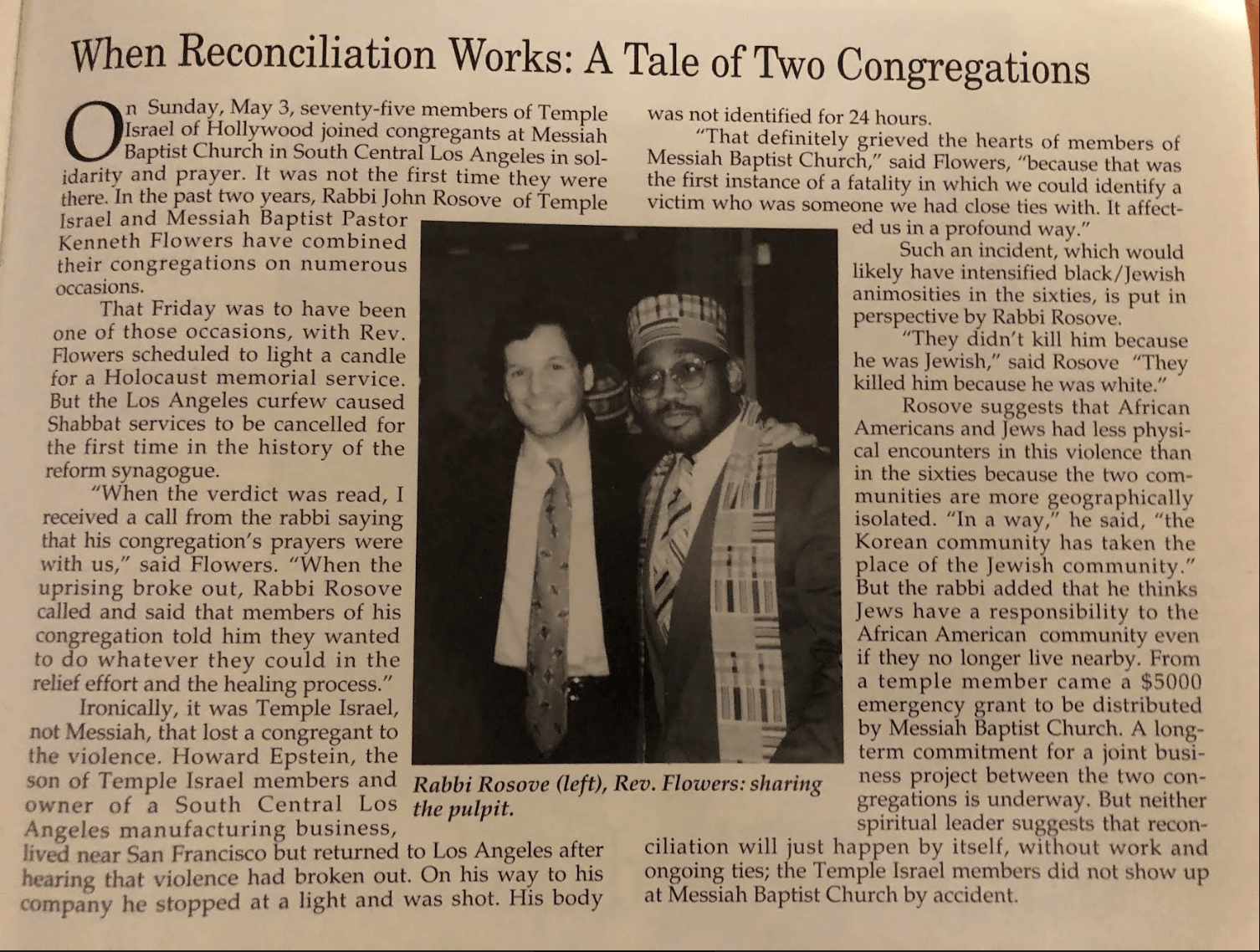

One of those stories was that of Rabbi John Rosove of Temple Israel of Hollywood and Pastor Kenneth Flowers of Messiah Baptist Church in South Central Los Angeles. The two had exchanged pulpits on several occasions by the time mayhem broke out following the April 29, 1992, acquittal of police officers in the beating of motorist Rodney King.

The congregations worshiped together during the violence, in which the synagogue, not the church, lost a member. The owner of a manufacturing business was fatally shot when he drove into the riot zone to check on his plant and employees. His death was grieved by both congregations.

My story ended there, but the relationship did not. In L.A.’s January 1994 earthquake, the church’s building was deemed uninhabitable. This week, in separate telephone interviews that echoed each other nearly word-for-word, the two clergymen related their conversation.

“I called Ken,” recalled Rosove. “I said, ‘What are you going to do next Sunday?’ He said, ‘I don’t know.’”

Flowers picked up the story: “Without hesitation, he said, ‘You can come worship at Temple Israel on Sunday.’ I said, ‘We have church. We preach about Jesus and the Gospel. We have music.’”

Rosove continued: “I said, ‘I know that, but when you take our chapel, it’s your church that morning and you say whatever you like.’”

Flowers took up the offer, with CNN and a local TV station capturing the service on camera. “Ken and I embraced and he called me ‘Brother John.’ It was broadcast all over the world,” Rosove said.

That church-in-a-shul lasted only one week, however. Not all of Messiah Baptist’s congregants attended or approved of it.

“I told them, we are the church wherever we go, even in a parking lot,” Flowers said.

A funeral home two blocks away from the damaged church became its longer-term temporary home. More permanent change came soon after, when Flowers accepted the pulpit of a prominent Detroit church.

“When he told me he was going to Detroit, my heart sank,” Rosove said. “When he left, we were told in no uncertain terms that the church wasn’t going to continue the covenant relationship.”

In Detroit, Flowers similarly planned to focus on his primary duties. “I said, ‘I’m not going to get involved with anything – not the NAACP, not the Jewish community.’”

That didn’t last long as word spread from Jews in Los Angeles to Detroit, Flowers said. “People in L.A. contacted them, saying, ‘Rev. Flowers is a friend of the Jewish community. Take care of him.’”

This time, it went beyond pulpit exchanges. Flowers not only accepted invitations to preach at Temple Beth El, Michigan’s oldest synagogue, but brought with him 750 worshippers from his new congregation, Greater New Mount Moriah Baptist Church. That was followed by nine trips to Israel, with groups including the Anti-Defamation League, the American Jewish Committee and AIPAC, at whose national conference Flowers has been a regular attendee and speaker.

“God has me more involved with the Jewish community than ever,” he said. “What began in L.A. blossomed years later.”

Yet not so where it started for him. At Messiah Baptist, Flowers’ successor was, and remains, the Rev. Perry Jones. Flowers, 61, said he asked Jones about continuing the relationship with Temple Israel when handing over the reins.

“He said, ‘We’ll see what the members say.’ It just never happened” – adding, nonjudgmentally, “Every pastor is different.”

Jones confirmed that, telling the Forward: “The leadership of both congregations would have to get together and have a meeting and discuss what they want to do. This isn’t something that’s a top priority for me.”

That doesn’t mean that L.A.’s Jewish and Black Christian congregations have stopped talking to each other. Rosove, 72 and now senior rabbi emeritus at Temple Israel, points proudly to a former assistant rabbi at the shul. Rabbi Jocee Hudson works full-time with LA Voice, a multiracial, multifaith organization composed of three dozen congregations focused on working together toward community empowerment.

More important personally is Rosove’s relationship with his friend. Though they haven’t seen each other in person in about five years, they keep in touch and get word about each other.

“My doctor visited Detroit and told me ‘this Black preacher was talking about you,’” Rosove said.

“It’s one of those relationships that you cherish.”