‘This is not a joke:’ Rabbis at the center of Texas synagogue hostage-taking share details of that day

Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker and Rabbi Angela Buchdahl met for the first time to talk about the day their lives intersected.

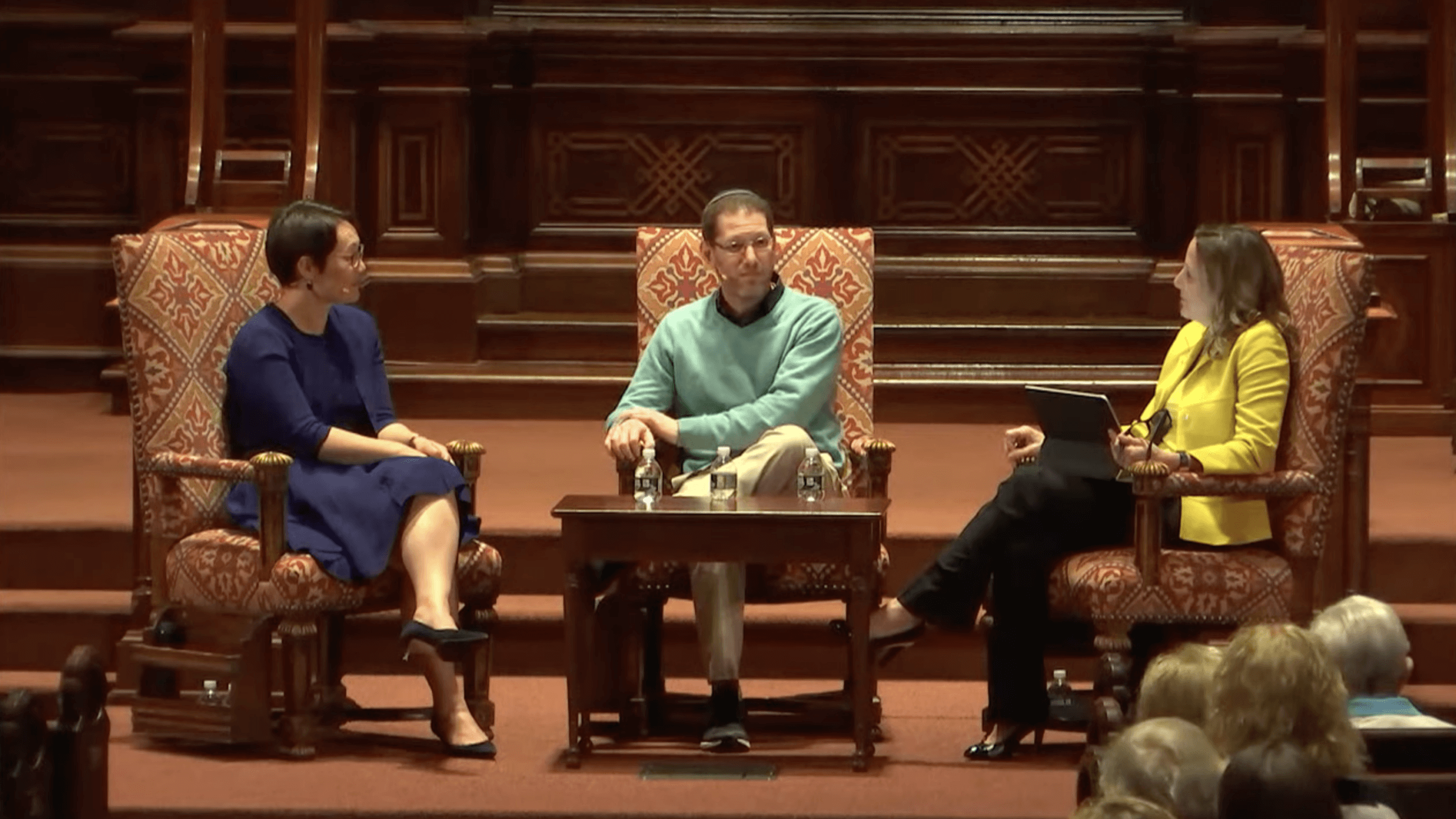

Rabbi Angela Buchdahl, left and Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker, center, in a conversation moderated by author Abigail Pogrebin at Manhattan’s Central Synagogue on May 3, 2022. Photo by YouTube screenshot

When Rabbi Angela Buchdahl saw that someone from Texas was trying to call her in January, she let it go to voicemail. She had no idea it was another rabbi who was at that moment being held hostage with three of his congregants.

And although Buchdahl doesn’t like to make a habit of using the phone on Shabbat, she was also busy on another call — checking in on her parents, who had not been feeling well.

But then she listened to the voicemail, 28 bizarre seconds in which a man claiming to be a rabbi calmly told her about a gunman, saying “He wants to talk to you.” Buchdahl wasn’t sure she should believe anything he said.

That rabbi turned out to be Charlie Cytron-Walker, the spiritual leader of a modest synagogue in Colleyville, Texas, who along with those three congregants survived a nearly 11-hour hostage-taking. At Buchdah’s Central Synagogue in Manhattan Tuesday night, nearly four months after the Jan. 15 incident, Cytron-Walker and Buchdal met for the first time to talk about the day, and how — in Buchdahl’s words — it feels like the two are now “bonded for life.” Sitting side by side, they shared what was going through their minds — and their strong feelings of responsibility to each other during and after that harrowing day.

The audience — which included members of both Central Synagogue and Temple Beth Israel of Colleyville — then heard the tape of the shocking voicemail Cytron-Walker left for Buchdahl. She had to listen to it three times, she said, before she decided that she needed to take action.

It went like this: “Angela, this is Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker. This is not a joke. I’m the rabbi at Congregation Beth Israel and Colleyville. We have an actual gunman who is claiming to have bombs and he wants to talk to you. If you can call me back at this number, that would be greatly appreciated. And again, this is not a joke.”

Cytron-Walker’s voice was astonishingly calm, noted the writer Abigail Pogrebin, who moderated the more than hour-long conversation between the two rabbis.

The gunman, a British man who flew to Texas, targeted Beth Israel as the synagogue closest to a federal prison that held the convicted terrorist Aafia Siddiqui, sometimes known as “Lady Al-Qaida.” He believed that Buchdahl was powerful enough to free the prisoner, who he called his “sister,” although she was not his relative. Speaking with Buchdahl, Cytron-Walker explained that to find her cell phone number, he had looked in a directory distributed by the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the umbrella group for rabbis in the Reform movement.

“And your cell phone is in the directory?” Pogrebin asked Buchdahl.

“Not anymore,” joked Buchdahl.

After listening to the voicemail several times, Buchdahl said, she gained some confidence in Cytron-Walker’s voice. “It didn’t sound like a teenage who was playing a joke. It sounded like someone was very serious, but I was but it was so surreal that I really actually couldn’t believe that it was real. And I didn’t know Charlie yet.”

So she began Googling: “Cytron-Walker,” “Colleyville,” and “Beth Israel.” They all seemed to fit together. Then Buchdahl began making calls herself — to the executive director of Central Synagogue and its head of security. Together, they decided she need to call Cytron-Walker back.

She had to call three times before he picked up. “And I said how are you doing? You said ‘not great actually,’” recalled Buchdal. “I just thought okay, he hasn’t totally lost his sense of humor.”

Cytron-Walker described the scene in his synagogue to her, she recalled. “And then you pretty quickly passed the phone to him.”

The gunman told Buchdahl there were bombs planted in New York, and he could order them detonated. He told her write down the name of the prisoner he wanted freed. He made her spell the name back to him. “And he said, ‘you have an hour to bring her to the synagogue. She’s in prison. That’s only 20 minutes away.’ And I said, ‘I’m not sure I can do that.’ But I’m you know, I was obviously trying to buy time.”

Over the next 10 hours, Cytron-Walker, Buchdahl and the FBI outside Beth Israel would try to negotiate with the gunman, who grew more belligerent in the last 90 minutes of the ordeal.

“I am running out of patience and you are running out of time,” Buchdahl remembers the gunman saying to her at one point, and then hanging up on her. She said she felt “completely responsible” for Cytron-Walker’s life at the point, and for the other congregants who remained with him; the group was able to negotiate for one hostage to be released earlier. She knew she couldn’t free the prisoners, but she somehow still felt that she should be able to help more.

Unknown to Cytron-Walker, who was himself considering an escape plan — eventually, he threw a chair at the gunman to distract him, and he and the two remaining congregants made a break for it — the FBI had decided to storm the building. Both they and he understood that the situation had taken an ominous turn. Seconds after the rabbi and congregants freed themselves, the FBI entered and killed the gunman.

Cytron-Walker, who in June will take a new pulpit at Temple Emanuel in Winston-Salem, turned to Buchdahl and apologized to her for what she went through. She protested that it wasn’t his fault. But he insisted that he should, because she had felt so responsible and powerless at the same time. “Oh my God, when you talk about that sense of responsibility,” he said. “That’s why I apologized, because I know that I — oh my gosh, how helpless right?”

Buchdahl said Cytron-Walker, who has been praised for his quick thinking in creating an opportunity to escape, also deserves to be honored for his behavior through the rest of the crisis. “It’s not just about the heroic act,” she said. “At the end, it was the way that you continued to treat the gunman as a human being, which enabled him to say, you know, he said to me even on the first phone call, ‘these are good people. I don’t want to hurt them.'”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Opinion Despite Netanyahu, Edan Alexander is finally free

-

Opinion A judge just released another pro-Palestinian activist. Here’s why that’s good for the Jews

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.