Boston’s Jews are getting a ‘Jewish tavern’ to study religious text — and drink beer

This Jewish tavern from the co-creators of Sefaria and PocketTorah aims to revolutionize Jewish communal spaces, in the spirit of the Frankfurt Lehrhaus of the 1920s

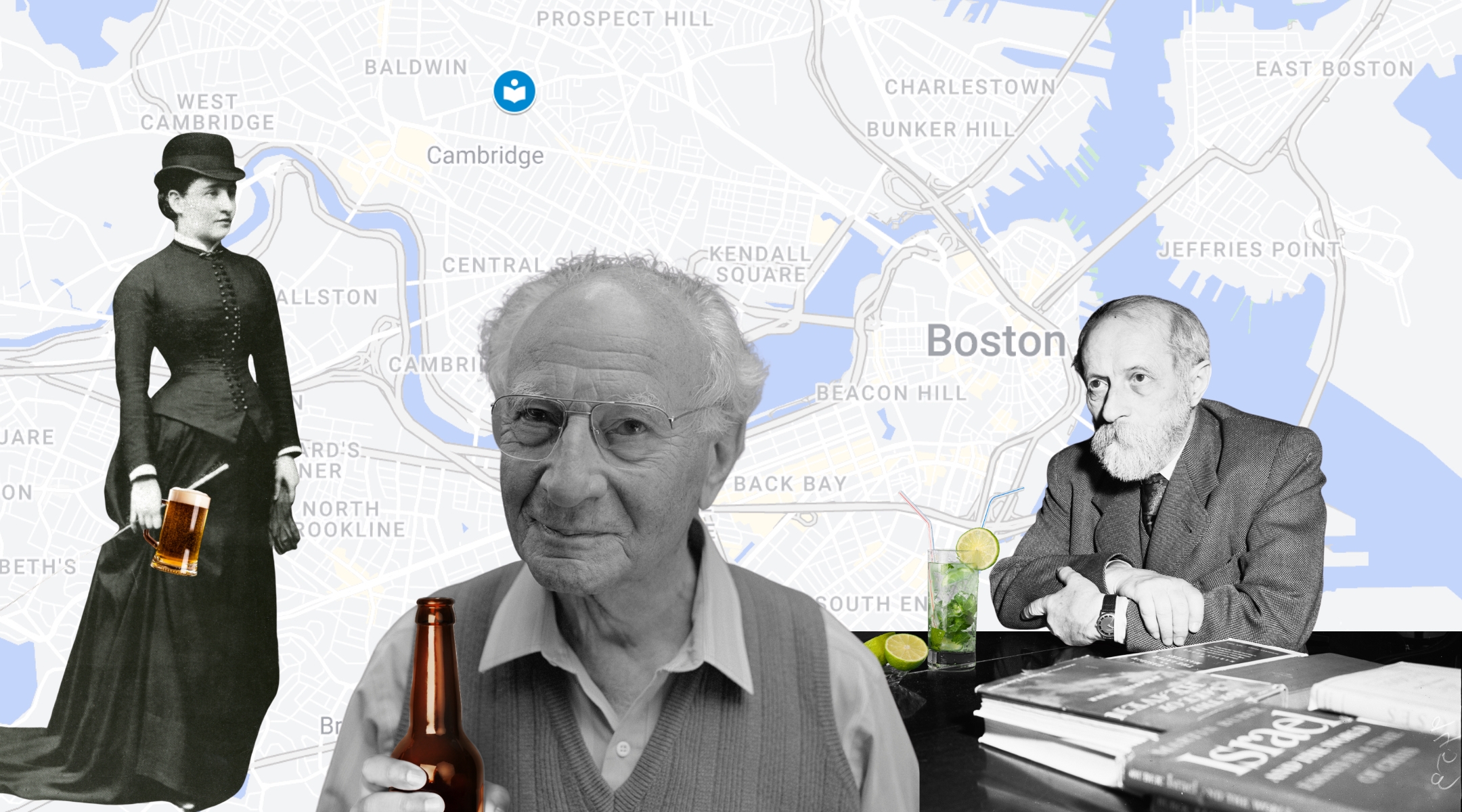

The Lehrhaus is inspired in part by Frankfurt’s Jewish House of Free Study, where intellectuals of the early 20th century like Bertha Pappenheim, Leo Lowenthal, and Martin Buber lectured and learned. (Getty Images. Design by Jackie Hajdenberg)

(JTA) — A century ago, German philosopher Franz Rosenzweig spearheaded the revival of intellectual Jewish life in the city of Frankfurt am Main with the “Freies Jüdisches Lehrhaus” — the Jewish House of Free Study.

As many as 1,100 adult students would attend lectures tailored to secular Jews and aimed at democratizing the kind of Jewish learning that was typically restricted to the beit midrash, or formal house of Jewish study.

Now, a Lehrhaus in the spirit of 1920s Frankfurt is coming to the Boston area. The brainchild of Rabbi Charlie Schwartz and Sefaria cofounder Joshua Foer, it will be a space for traditional paired study of the Talmud and other Jewish texts, called “chevruta,” aimed at Jews across the religious spectrum.

With a full menu of food and drinks inspired by flavors from across the Jewish Diaspora, serious study won’t be the only reason to stop in, and the Boston Lehrhaus founders hope this will mean more casual encounters with Jewish culture — even from people who aren’t Jewish.

“If someone walks in off the street and doesn’t realize it’s a Jewish space and they’re encountered by all this wonderfulness and surprise and delight and joy and delicious food, then that’s great,” Schwartz said. “Most people who encounter the space who aren’t Jewish will encounter it primarily as a Jewish tavern, in the same way they might encounter a bagel shop or a Jewish deli or a Jewish Bukharian place.”

The Boston Lehrhaus will be a space for traditional paired study of the Talmud and other Jewish texts, called “chevruta,” aimed at Jews across the religious spectrum. (Image courtesy of Charlie Schwartz)

A drink menu designed by Boston-based, award-winning bartender Naomi Levy of Maccabee Bar, a Jewish popup bar for the winter season, will include a Yemenite espresso martini with the spice blend hawaij, a spicy schug margarita and a “Summer in Krakow” cocktail made with strawberry, Sorel liqueur and gin. James Beard Award-nominated chef Michael Leviton and Boston native chef Noah Clickstein are consulting on the food menu, which the Lehrhaus founders are calling “kosher pescatarian.”

The programming itself will be a combination of partnered learning, classes and public events including lectures from celebrities and intellectuals in the secular space in conversation with scholars, rabbis and educators. The educational programming, created with assistance from Hadar and the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America — two non-denominational Jewish think tanks based in New York but expanding their presence in other cities — is geared toward adults.

The food, booze and learning are in service, however, of meeting a serious challenge: While people of all religious observance are meant to feel welcome at the Lehrhaus, the creators are aiming to reach a cohort of young Jews who are interested in Judaism but may not feel connected to traditional religious spaces — and they’re betting that rich Jewish content, not just social engagements, are the key to doing so.

“The goal isn’t to make people more religious, but rather for people to engage deeply in Jewish learning and chevruta,” Schwartz said. “We want to be able to say, ‘if you are observant, this could be a spot for you. If you’re not observant, there’s still amazing things about Jewish texts that can help ground us and guide us and create community.’”

That sort of outreach has attracted major Jewish charitable organizations, including the Boston Combined Jewish Philanthropies, the Jim Joseph Foundation, the Maimonides Fund, the One8 Foundation, Natan, the Aviv Foundation, and the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies.

The Los Angeles-based Kripke Institute was not a funder, but Lehrhaus partnered with the 501c3 to process initial grants and donations.

Ron Wolfson, president of the Kripke Institute and a professor of education at American Jewish University, said the prospect of a place like the Lehrhaus is deeply exciting to educators like him. Based on the work that Schwartz and Foer have done in the past — Schwartz as the co-creator of PocketTorah, an application to help Torah readers learn to chant and Foer, as the co-creator of Sefaria, the online open-source digital library of Jewish text — Wolfson is confident in their latest project.

“We need spaces where the barriers of entry are low and the expectation of an immersive experience is high. Lehrhaus checks those boxes,” Wolfson said. “It will become a very hip, sacred space very quickly.”

While there are many young Jews in the Greater Boston area, half of the area’s 250,000 Jews consider themselves “unaffiliated,” according to a 2015 Brandeis University study. Institutions like Hillel International, the Chabad-Lubavitch movement and Moishe House do outreach to young people in the area, but the Lehrhaus founders say Jewish organizational activity outside of the synagogue space and geared toward young adults is still lacking, given the density and size of the Jewish population.

The post-college set of Greater Boston comprises nearly a quarter of the Jewish population there and is largely concentrated in Somerville, Cambridge and Central Boston.

Wolfson, the author of two books on creating Jewish spaces, cited a finding in the Pew study saying more than 94% of Jews are proud to be Jewish. The survey also found that Jews under age 50 “are significantly more apt than those who are older” to say they are “just not interested” in attending synagogue services, and instead relate to Judaism through cultural and social expressions. One way that some communities have tried to solve this problem is by organizing events outside of the synagogue, like organized bar crawls.

“Charlie and Joshua are taking a huge step further by creating the bar,” Wolfson said. “It’s a one-stop experience that meets everybody’s needs for engagement. And that’s very cool.”

Foer and Schwartz are optimistic about the future of the Lehrhaus — Schwartz left his job at Hillel International in June to focus on the Lehrhaus full-time.

Still, success is not guaranteed. Other similar, unaffiliated ventures — some with the same name — have sprung up over the decades in other cities, with mixed results.

In 1999, Makor opened on New York’s Upper West Side with a similar premise of being the kind of place where Jews in their 20s and 30s could grab a beer, study kabbalah, mingle with singles and enjoy art installations and musical performances. Award-winning singer-songwriter Norah Jones performed at Makor dozens of times early in her career, before it closed in 2006.

Lehrhaus Judaica, a Berkeley-based adult educational organization founded in 1974, closed in 2021 due to financial difficulties. It recently reopened under new leadership and a rebranding as “The New Lehrhaus.”

Even the success of the Frankfurt Lehrhaus was limited, despite its impressive roster of leading Jewish intellectuals like the writer Shai Agnon; philosophers Gershom Scholem, Leo Lowenthal, and Martin Buber; and the feminist and activist Bertha Pappenheim. The original institution was closed in 1930, then reopened by Buber in 1933. It was closed permanently by the Nazi regime in 1938.

Schwartz and Foer want people to recognize the Jewish tavern as a category of its own, like the Irish pub — and that it has its own historical precedent. The “kretshme” (Yiddish for “tavern”) was an important fixture of Eastern European Jewish life during the Jewish mystical revival of the 19th century, according to historian Glenn Dynner. Like the western European coffee houses of the Enlightenment era, Jewish taverns functioned as a “third space” where people could gather and discuss intellectual and political issues over alcohol.

The Boston Lehrhaus, which is expect to open after the High Holidays this fall, is trying to remain true to the intellectual environment of its German predecessor while appealing to its young community members.

“Quite a few people will come for the food and drink and some of them will stay for the Torah,” Foer said. “And that would be this thing working.”

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.