First PersonWhat I learned about swimming — and life — from an Israeli who survived the Munich massacre

Avraham Melamed, now 78, looks back on what happened in the Olympic Village 50 years ago

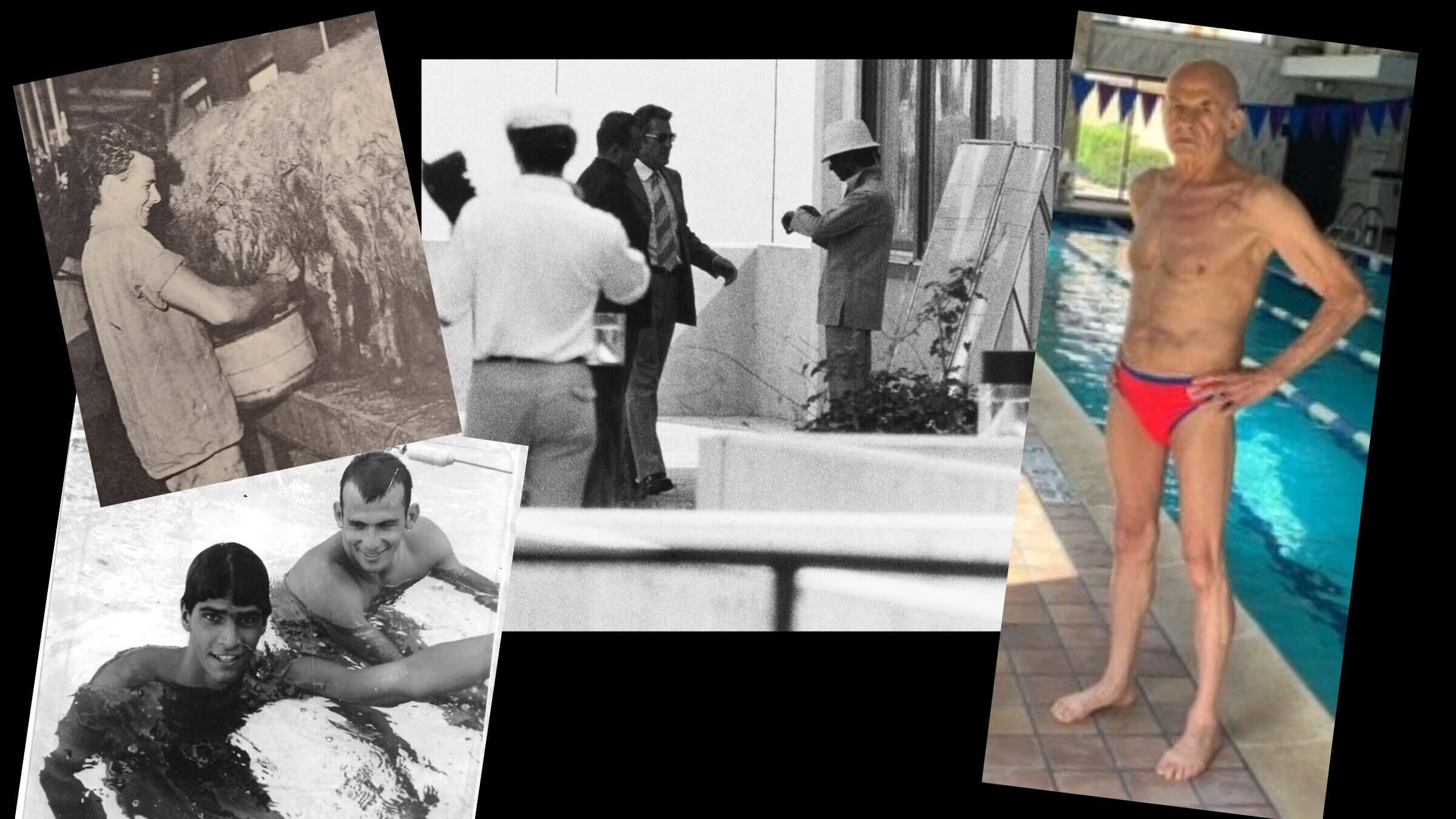

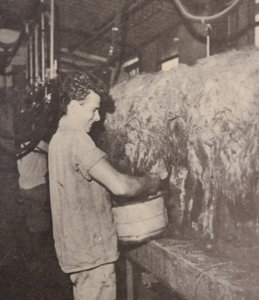

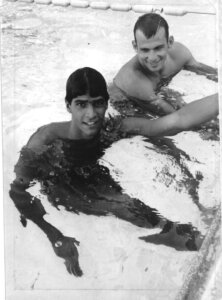

Top left: Avraham Melamed on a kibbutz; bottom left, Melamed with Mark Spitz; center, officials attempt to negotiate with terrorists at the 1972 Munich Games; right, Melamed today at a Westchester pool. Courtesy of Melamed (kibbutz); Galey Gil (Spitz); Getty (Munich); Marc Shenfield (pool)

Meet my swimming instructor, Avraham Melamed. He’s 78 years old and goes by the nickname Bey. He grew up on a kibbutz, milking sheep by hand, and competed for Israel in the 1964 and 1968 Olympic Games.

Then, 50 years ago, in 1972, he survived the terror attacks on the Olympic Village in Munich, escaping through a back door after seeing a friend lying in a pool of blood.

Melamed does not like to talk about Munich. “It was a tornado in my life, but it passed,” he told me over dinner in my home. Later, he wrote me: “Helpless and unable to avoid thinking of the Holocaust, we watched our friends being led to their final destination.”

I was 23 during the Munich Games, and remember watching the terrifying TV reports as eight terrorists from the Palestinian group Black September killed 11 members of the Israeli team.

When I heard about Melamed from my yoga instructor, I was drawn to his history as well as his reputation as a sensitive coach. We met in February, when I decided, at age 73, to take swim lessons to alleviate the aches and pains of arthritis. Now I see him several times a week at a pool in New York’s Westchester County where he trains triathletes, kids with disabilities and novices like me.

These months with Melamed have improved my health and how I look in the pool. But I’ve learned much more than stroke technique from this quiet, intuitive man who witnessed the worst attack in Olympic history. Over time, as he told me the story of his life, he’s shared his thoughts on what happened in Munich as well.

‘Let the water carry you’

Most days, Bey can be seen in his Speedo warming up on the deck of the pool at the Premier Athletic Club in Montrose, New York, rotating his shoulders and touching his nose to his knees. This follows a 90-minute routine of stretching and breathing exercises before breakfast. He’s a vegetarian who mostly eats fruit, nuts and Israeli-style salads. Occasionally, he enjoys a piece of chocolate.

When you ask him how to stay healthy, he’ll tell you to relax, stretch, breathe, “avoid injury and engage in activities that increase blood flow.”

“Let the water carry you,” he often says. “It could not care less whether you are an Olympic champion or, forgive my Yiddish, an alta yenta”— meaning an old lady.

Growing up on a kibbutz

Bey grew up in northern Israel on Kibbutz Ramat Yohanan, where his dad was one of the founders. He remembers running from the milking shed to the pool for an afternoon workout. Despite his asthma — he still keeps an inhaler in his swim bag — Bey became an Israeli champion, winning silver medals in the 100-meter butterfly and the medley relay at the 1966 Asian Games in Bangkok and competing in the 1964 and 1968 Olympics. Israeli friends remember trading the equivalent of American baseball cards featuring his picture. In ’68, one of his competitors was Mark Spitz, who went on to become America’s greatest swimmer. They met again at the 1969 Maccabiah Games.

Bey first came to the United States in 1970 on a swimming scholarship to West Liberty State College — now West Virginia University. He then recruited three more Israeli swimmers to join him, turning the school into an unlikely pool powerhouse. He got the nickname Bey in college — it’s short for Beinush, an endearing term, from the Hebrew word for son, ben, which his family always used.

Due to a confrontation with the Israeli Sport Federation, he was not chosen for the Israeli Olympic team in 1972, but went to Munich anyhow as a private coach and to report on the games for the Israeli daily Yedioth Ahronoth.

“One of those killed in Munich was my teacher and I knew the others from my years in international competition,” he said in a Swimmer Magazine profile in 2011. “It was horrible.”

Putting the tragedy behind him

Bey told me that he returned to the U.S. shortly afterwards, “away from the limelight and wrapped in an internal brainstorm.”

“I tried to put the tragedy in my rear mirror and go back to some kind of normalcy,” he said in an email.

But as the unofficial spokesman for the four Israeli swimmers on campus, he was regularly recruited to speak at fundraisers for nearby Jewish organizations, and was often asked about Munich.

“Some of those funds were used to pay our tuition and our cost of living, so I cooperated,” Bey recalled. “But inside, it felt to me like I was dancing on the graves of the athletes who lost their lives.”

Over time, Bey said, he “began to think about what brings people to where they are willing to take such horrific action, to where they are willing to die for an idea by killing people they never met – athletes in an event that stands for peace.” He sees “despair” as the likely explanation, because, as he puts it, “Israel holds land the Palestinians consider their own.”

He described himself as “a person raised on the notion that Israel is a country promoting peace and justice,” and said the “deep divide” between the two peoples should be addressed not through terror but through geopolitical dialogue based on empathy.

“One way towards moving ahead is by placing oneself in the other’s shoes and asking this question: ‘What is the maximum I can give up in order to move forward with the minimum I cannot give up?’” Bey posited. “Listening to the opposite side, putting yourself in ‘their’ place, I concluded, is a much more effective path to resolve differences. Not easy, indeed, but a good place to start.”

A meticulous instructor

For now, though, there is swimming. Bey is a meticulous instructor who meets each student where they are and takes pleasure in crafting individualized strategies. After each lesson, he emails a memo pointing out where I showed progress and noting areas for improvement.

An amateur photographer, he often uses images to get his message across. “Think of yourself as a skewer on a grill, rotating,” he said once. “Imagine your arms are oars.” Another time, to help improve my head position in backstroke, he texted an overhead photo of a cloud-streaked sky captioned: “The View from Your Lane.”

He told me he has been passionate about photography since he was a boy, when his uncle, who lived in Detroit, visited the kibbutz with a Polaroid camera. These days, using his Samsung S21, Bey chases beauty in many forms, especially reflections in water, windows, sand and other surfaces, posting many on Instagram (@beymelamed).

One of Bey’s frequent suggestions is to watch good swimmers in the pool. “Do what they do,” he repeats. “Hear what they hear. Feel what they feel.”

When I first told Bey I wanted to write about his history as the 50th anniversary of Munich approached, he demurred. Then he changed his mind.

“Till this day, I feel uncomfortable when my presence in this horror is used to promote something,” he told me. “The same goes for this 50th anniversary. I want an anniversary to stand for a positive event, not a horrific one. Yes, this is reality and, yes, I am just a small part of it. I hope that with respect to the Munich disaster, it remains small.”