Ken Burns’ PBS documentary ‘The U.S. And The Holocaust’ asks hard questions about how Americans treated Jews and immigrants during wartime

Working with top historians, Burns and his co-directors cover some surprising territory in their retelling of the American response

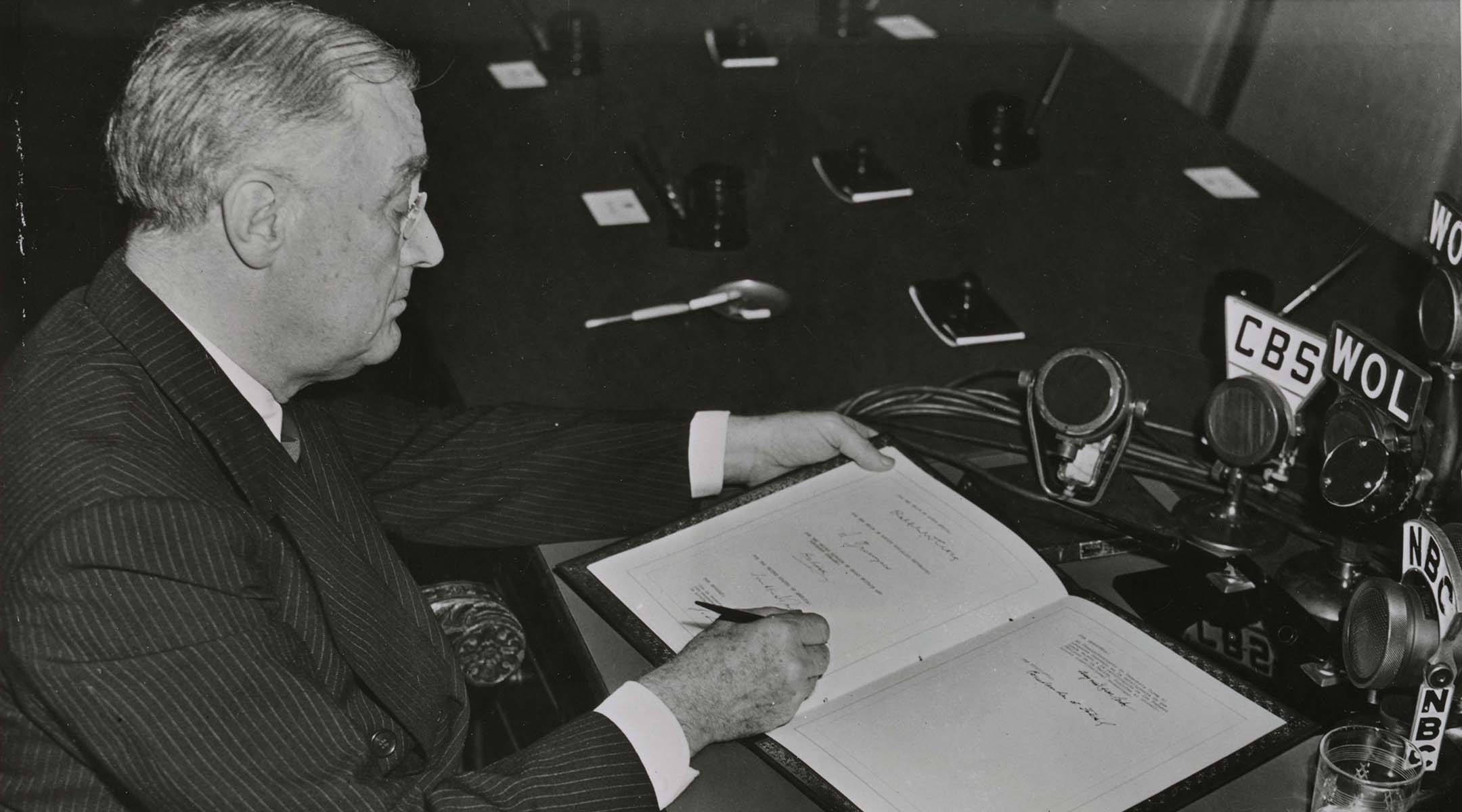

President Franklin Roosevelt in Washington, D.C., Nov. 9, 1943. (National Archives and Records Administration)

(JTA) — One of the first people introduced in Ken Burns’ new documentary series about the Holocaust is Otto, a Jewish man seen in the series’ first episode who tries to secure passage to America for his family but gets stymied by the country’s fierce anti-immigration legislation.

It isn’t until the third episode that viewers learn that Otto’s daughter is nicknamed Anne, and the pieces fall into place: He’s the father of Anne Frank, the Holocaust’s most famous victim.

Burns calls the delayed detail a “hidden ball trick,” hoping that an audience with only passing knowledge of the Frank family will not immediately clue into the fact that Otto was Anne’s father. Burns and his co-directors, two Jewish filmmakers, want their viewers to ponder the question of what the U.S. government felt Anne’s life was worth when she was still a living, breathing Jewish child and not yet a world-famous author and martyr of the human condition.

“It was important to us to look at a way in which you can rearrange the familiar tropes so that you see: This is a family that is getting the hell out of Germany, and hoping eventually to put more distance between them by going to the United States, which basically in the majority of the citizens and in the policy of its government does not want them,” Burns told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Burns is the foremost documentarian of American history, with iconic works such as “The Civil War,” “Jazz” and “Baseball” (where he explained the real hidden ball trick, an on-field sleight of hand), turning PBS programs into must-see TV multiple times over the past four decades. His latest, “The U.S. and the Holocaust,” premieres on the public broadcaster Sept. 18 and will air over three nights.

The project took seven years to complete. In 2015, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum reached out to Burns with a request: Would he consider making a film about America during the Holocaust?

A German policeman checks the identification papers of Jewish people in the Krakow, Poland, 1941. (National Archives in Krakow)

Burns and his longtime co-directors, Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein, along with writer Geoffrey C. Ward, had already been considering such a project. Their 2007 miniseries about World War II and their 2014 project about the Roosevelts covered historical periods that overlapped with the Holocaust but did not explore the subject in depth — and their makers recognized the gap.

Produced in partnership with the museum and the USC Shoah Foundation, and drawing on the latest research about the time period, the resulting six-hour series explores the events of the Holocaust in granular detail. But it also chronicles the xenophobic and antisemitic climate in America in the years leading up to the Nazi genocide of Europe’s Jews: a nation largely hostile to any kind of refugee, particularly Jewish ones, and reluctant to intervene in a war on their behalf.

The series paints a picture of a country largely failing the century’s greatest moral crisis, through a combination of bureaucratic ineptitude, political skittishness and open bigotry emanating from the streets to the most vaunted chambers of power — while a handful of heroes, working mostly on the sidelines, succeeded in helping small numbers of people.

“There was a way, because we were relating it to the U.S., that you could get a different and perhaps fresher kind of picture,” Burns said. “The United States doesn’t do anything, and then all of a sudden it does. They’re bad guys, and then they’re good guys.”

The filmmakers hope such a message will have modern resonance, especially as it arrives in a very different world from the one in which work on it began: amid a growing climate of authoritarian governments, right-wing extremism, Holocaust denialism and fierce debates over how to frame American history in the classroom.

For these reasons and more, Burns said, “I will never work on a more important film.”

The film was an especially personal journey for Botstein and Novick, who are both Jewish. Bostein’s father (Bard College president Leon Botstein) was born in Switzerland in 1946, to two Polish Jews who had met in medical school in Zurich and later came to the United States as refugees. She is a first-generation American and said making the film helped her better understand her family’s survival.

“My grandmother used to say to me: ‘If someone shook you in the middle of the night, what would you say? Are you an American? Are you a Jew? Are you a woman? Are you Sarah?’” Botstein said. “Because her identity had defined everything that ever happened to her, and I didn’t have that experience living in a fairly liberal part of New York State.”

Novick, meanwhile, was raised in the United States, in a secular Jewish family that had already been here for generations. For her, the project was eye-opening in a different way.

“I understand better now, I think, the world that my grandparents, or sometimes great-grandparents, grew up in, and how antisemitic America really was,” she said.

Like most projects by Florentine Films, Burns’ production company, “The U.S. And The Holocaust” tells its story with copious historical documents — in this case, photographs, letters, and newsreel footage — often read aloud by celebrities, including Meryl Streep, Liam Neeson, Hope Davis and Werner Herzog. They voice the stories of Frank and others like him who sought refuge in the United States but died in gas chambers and concentration camps instead.

It is also supplemented by extensive interviews with Holocaust survivors and historians, most prominently Deborah Lipstadt, an influential Holocaust scholar and currently the U.S. State Department’s special envoy on antisemitism. Lipstadt delivers what the directors saw as the film’s most haunting conclusion: that the Nazis achieved their goal of permanently crippling the global Jewish population, which has not been fully replenished in the decades since the Holocaust.

The American focus means the film takes 30 minutes to arrive in Germany. The timeline begins not with Adolf Hitler’s rise to power but with the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, an American law that set national quotas on all immigrants to the country and would come to factor heavily into U.S. refugee policy during Europe’s mass expulsion of Jews.

The filmmakers take a wide speep in establishing the racist political climate of the time, discussing the Chinese Exclusion Act of the 19th century; Theodore Roosevelt’s love of eugenics; Henry Ford’s public campaign of antisemitism; and Jim Crow laws, which rendered Black people second-class citizens and which Hitler would eventually draw from when crafting his own race laws.

“To set the table meant we had to go pretty far back,” Novick said.

The chronological approach places particular emphasis on what had already transpired in Europe by the time Americans got significantly involved: the “Holocaust by bullets,” for example, in which more than 1.5 million of what would ultimately be 6 million dead Jews were slaughtered by gunfire and dumped in mass graves throughout Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe before the concentration camps were even constructed.

Members of the Sturmabteilung or SA — a Nazi paramilitary organization. (National Archives and Records Administration)

As it details the horrors unfolding in Europe, the film focuses on the rise of Nazi-sympathizer movements on the homefront, including the America First Committee, and breaks down the tensions within the State Department, where antisemitic officials in positions of power undermined efforts to intervene diplomatically on the behalf of Jews.

The film also discusses divisions within the American Jewish community over whether to let in so many Jewish refugees. Twenty-five percent of American Jews at the time didn’t want to let any more in, some because they looked down on the Eastern European refugees as poor and unassimilated, and others because they were scared of making life worse for the Jews still in Europe if they spoke out too forcefully.

“It took me a while to really get my mind around the idea that there was a significant voice within a powerful Jewish American community that [believed] we shouldn’t say too much because it will just stir the pot and awaken more antisemitism,” Novick said.

There were heroes on the homefront, too, and the film relays their stories. Varian Fry and Raoul Wallenberg, who traveled to Europe to rescue as many Jews as they could, are depicted, as are the efforts of the U.S. War Refugee Board and American diplomats such as John Paley. The advocacy of figures such as Jan Karski, Rabbi Stephen Wise, Ben Hecht and Peter Bergson is also spotlighted.

To depict the history, the filmmakers relied heavily on their advisory board (they have one for every project they take on) to determine how much time to devote to various historical events, whether to show certain images or merely describe them and how to describe them. “We don’t go anywhere without our board of advisors,” Botstein said.

For “The U.S. and the Holocaust,” the advisors included Holocaust historians such as Debórah Dwork, Peter Hayes and Richard Breitman, as well as scholars of race history such as Nell Irvin Painter, Mae M. Ngai and Howard Bryant.

Often the advisors disagreed on how to depict moments in history, and this disagreement is sometimes reflected in the film itself. A debate over whether the United States should have bombed Auschwitz, or even the trains leading into the death camp, echoed in the advisors’ room just as much as it did in the highest levels of government in the war’s waning months. The film reproduces those debates, quoting from historians who argue both points.

Immigrants waiting to be transferred at Ellis Island, Oct. 30, 1912. (Library of Congress)

The film’s treatment of Franklin D. Roosevelt is also notable given Burns’ demonstrated interest in the U.S. president. Many historians today fault Roosevelt for failing to take more decisive action to prevent further bloodshed at key moments in the war. The director noted that the new series is more critical of FDR’s actions during the Holocaust than his earlier series “The Roosevelts” was, but Burns still believes the president was mostly acting within his means as a politician. “He could not wave a magic wand,” he said. “He was not the emperor or a king.”

All Burns films are released with teaching guides and are intended for use in the classroom, but getting “The U.S. and the Holocaust” into schools was of particular importance to the filmmakers because they saw an opportunity to fit it into the dozens of statewide Holocaust education mandates that have been passed.

And also, Novick said, because the filmmakers have noticed the rise of various far-right, white supremacist ideologies, including many figures who espouse Holocaust denial. “It’s a never-ending battle that has to be fought,” she said. The film itself doesn’t engage with such denialists.

In their publicity for the film, Burns and company are partnering with several organizations to try to bring the Holocaust’s lessons into the modern day, including the International Rescue Committee, a refugee aid agency, and the U.S. government-funded think tank Freedom House.

The producers asked JTA not to give away the details of the film’s ending — an unusual request for a Holocaust documentary. But the reason is that Burns and his team don’t end with the camps’ liberation in 1945. Instead, they come up to the present, in unexpected ways.

“Most of our films come up to the present,” Burns said. “And we would be remiss if we did not take on this most gargantuan of topics, and not say that this is rhyming so much with the present.”

When asked why the film makes some of the connections it makes, Burns quoted a line Lipstadt delivers in the film: “If ‘the time to stop a Holocaust is before it happens,’ then it means you have to lay on the table the ingredients that go into it. Maybe these ingredients don’t add up to it… But if you’re seeing people assembling, in the kitchen, the same ingredients, you’ve got to say, you cannot wait until the meal is prepared.”

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.