First Person34 years ago I left Ukraine because it was no place for Jews. I’m not ready to leave again.

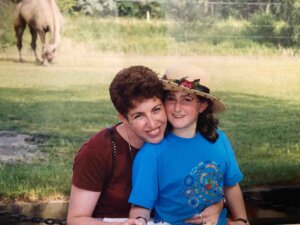

‘I swore I would never set foot in the country again. Yet here I am,’ writes Helen Chervitz

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Today, when I walk the streets of Kyiv, I think of the days when my husband and I waited to leave the country with our baby daughter. Ukraine was no place for Jews, and we longed for a better life in the U.S., where the discrimination we faced here would not place limits on our futures.

We became American citizens, and had a good life in the U.S., first in the Boston area, and then in New York. I thought I’d never go back to Ukraine. But I did, long before this horrendous war broke out. Now people ask me, “Why do you stay? You could leave at any time and live your American lives again.”

They also ask, as they remind me that I left Ukraine because of antisemitism, “What’s it like to be a Jew in Ukraine today?”

As a journalist, I usually write about other people. (And before this war I used to write about fashion, not current events.) But I understand that my story is intertwined with what is happening today in Ukraine, and its history. So I’m sharing, in hopes that it helps to explain the worlds that I’ve lived in, as much as it tells you about me.

Jewish — in Soviet Ukraine

Even as a small child in Ukraine, it was very clear to me that Jews were treated differently than other people, as second-class citizens. That was the case even though my family was not observant, and didn’t know much about Judaism.

On official documents — the fifth line to be exact — from school forms to passports, our nationality was marked “Jewish,” not “Ukrainian” or “Russian.” Jewish people called it the “damn fifth line.” It was like a curse, assuring that we would always be treated with disdain, and barred from educational and professional opportunities.

I experienced antisemitism from both those who acted out of ignorance, parroting the beliefs of their parents, and others who, hostile and occasionally violent, seemed eager to hurt Jews.

When I was ready for college, I had little choice. I was a serious swimmer, and competed on the Ukrainian junior national team. But I didn’t want to make a career of athletics, and yet, as a Jew, that was the only college program that would accept me in Ukraine. I then went to Moscow, where antisemitism was not as rampant, and earned a master’s degree in math.

After I graduated with honors, I couldn’t get a job for a year because I was Jewish.

And in daily life, it seemed antisemitism could strike anywhere, unexpectedly. Strangers would judge me to be Jewish by my looks, and lash out.

There was the time at a restaurant when I, then 19, asked the people at the table next to ours if they could pass the salt shaker. One of them, a man, threw it at my head, yelling, “You think it’s not enough that you eat our bread?”

That same year, I was grabbed by my coat and thrown off a bus by a passenger who announced that I was Jewish. I can still hear him addressing my non-Jewish companion: “Do you know who your friend is? Obviously not!”

Some of my friends distanced themselves from me when they found out I was Jewish. Others remained friendly, but let me know that I was cool, unlike other Jews.

No wonder so many Soviet children were taught by their parents to hide their Jewishness. My husband and I wanted to liberate ourselves from this antisemitism, and we didn’t want our child to grow up in such a country.

An American life

In the late 1980s, the Soviets finally buckled to international pressure and agreed to allow Jews to leave Ukraine. As soon as we applied to emigrate, my husband and I were stripped of our citizenship and lost our jobs.

We had to wait 10 months before we were allowed to go, and as we left the country, customs officers combed through our belongings, tossing most of what we had packed into a trash can, including my swimming medals and our baby’s formula.

We made our new home north of Boston, because our sponsor, my husband’s uncle, lived there, and quickly came to understand that the North Shore is home to a vibrant Jewish community.

Two weeks after we arrived, I applied for a job as aquatics director at the Jewish Community Center of the North Shore in Marblehead. There were 12 applicants and three rounds of interviews, and when I got the offer, the feeling was beyond happiness. This could never have happened in Ukraine, regardless of my qualifications.

I also discovered that in my new home, being Jewish was something to be proud of, not hidden. At the JCC, most of my colleagues and many of the children I taught were Jewish. Other Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union became our friends, and among them, many began to learn about and practice Judaism, and became active synagogue members.

My husband and I never became observant, yet we connected our daughter to Jewish life and culture. She spent summers at Jewish camps and twice went to Israel for cultural and educational trips organized by American Jewish organizations. She now works at the Vilna Shul in Boston.

As for me, I was proud of my work at the JCC, where I took the swim team from last place in the league to a championship title. But I wanted to do what I couldn’t in Ukraine — to study and work in the art world. My husband was doing well as a stockbroker, which enabled me to open a gallery on Boston’s Newbury Street. There I curated contemporary exhibits, including one showcasing Soviet artists — both those who stayed and those who had left.

Bostonians’ appetite for modern art wasn’t all I hoped for, so I accepted an offer as a marketing director for a fashion designer whose pieces I consider works of art. That led to courses in fashion design, and trips to Paris for Fashion Weeks. I learned French so I could conduct business in France. The brand I worked for took off in Europe, the U.S. and Japan. That’s how, in middle age, my career in fashion began.

My family was prospering in the U.S., and my gratitude to the country and American Jews for the sanctuary given to us is beyond words. I have never regretted our decision to leave Ukraine. I swore I would never set foot in the country again.

Yet here I am.

A different Ukraine

After 25 years in Swampscott, Massachusetts, and five in New York, my husband and I moved back to Ukraine. He had a business venture he wanted to pursue. The idea was to stay for just a year.

But we have been back for a decade, due to changing political and economic circumstances.

Readjusting to life in Kyiv was hard. But the city grew on me. And it is now a very different place from the one I left as a new mother.

The world has opened up to Ukraine, and it has moved far in the direction of democracy, freedom and tolerance. People began to study about other religions and cultures.

And antisemitism is not ever-present. On the contrary, being a Jew in Ukraine is even kind of cool. Some of the non-Jewish students I tutor in English search for Jewish ancestors, study Judaism and wear Magen David necklaces.

Gone is the state-sponsored antisemitism Jews endured under the Nazis and the Soviets. And incredibly, in 2019 Ukrainians elected a Jewish president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, by a landslide — 73% of the vote. At one point, Ukraine was the only country in the world, outside Israel, with a Jewish president and prime minister.

And after the mass exodus of Jews from Ukraine in the wake of the Soviet Union’s fall, those remaining have managed to resurrect old Jewish communities and to build new ones. There are an estimated 100,000 Jews in Ukraine today, and in recent years, synagogues, Jewish schools and cultural centers have cropped up.

Importantly, most Ukrainians see Jews as part of Ukraine’s history.

Of course there is still antisemitism in Ukraine, just like there is everywhere. In the last five years, it has festered in particular within nationalist groups, who have a long history of anti-Jewish leaders and alliances. Streets and statues around Ukraine, some of them newly erected, pay tribute to the nationalists who collaborated with the Nazis. They make Jews here uncomfortable.

And even though Ukraine is now proud of its Jewish president, it still doesn’t have the will or tools to effectively prosecute hate crimes against Jews. Ukrainian officials, at best, charge perpetrators with “hooliganism.”

Still, what I notice in Ukraine now, is that the talk about Jews centers on their cultural and spiritual contributions to the country — not their otherness or victimhood.

I live in the heart of Kyiv, around the corner from its main thoroughfare, Khreshchatyk Street. When the war broke out I saw its citizens suffer. They waited in lines for food even longer than in Soviet times, and feared the Russian army would move closer.

Life is much better here than at the war’s start. Children are back in school and my gym has reopened so I have resumed swimming. But however scary it was to remain in the city after Vladimir Putin’s invasion, there were many Kyivites like us, who decided to stay and defy his attempts to terrorize us.

We, who once risked everything to leave Ukraine, now feel tied to this city and its people — Jews and non-Jews alike.