Gifted to a bar mitzvah boy in 1936, a rescued book reunited two families. What other stories do Nazi-looted books tell?

The National Library of Israel wants to take a closer look at 35,000 books in its collection that had been stolen by the Nazis

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Those who lost family in the Holocaust can spend years trying to recover the identities of the dead, poring over documents and visiting towns and cities where Jews once lived.

Sometimes, though, it’s a book that connects the present and the past.

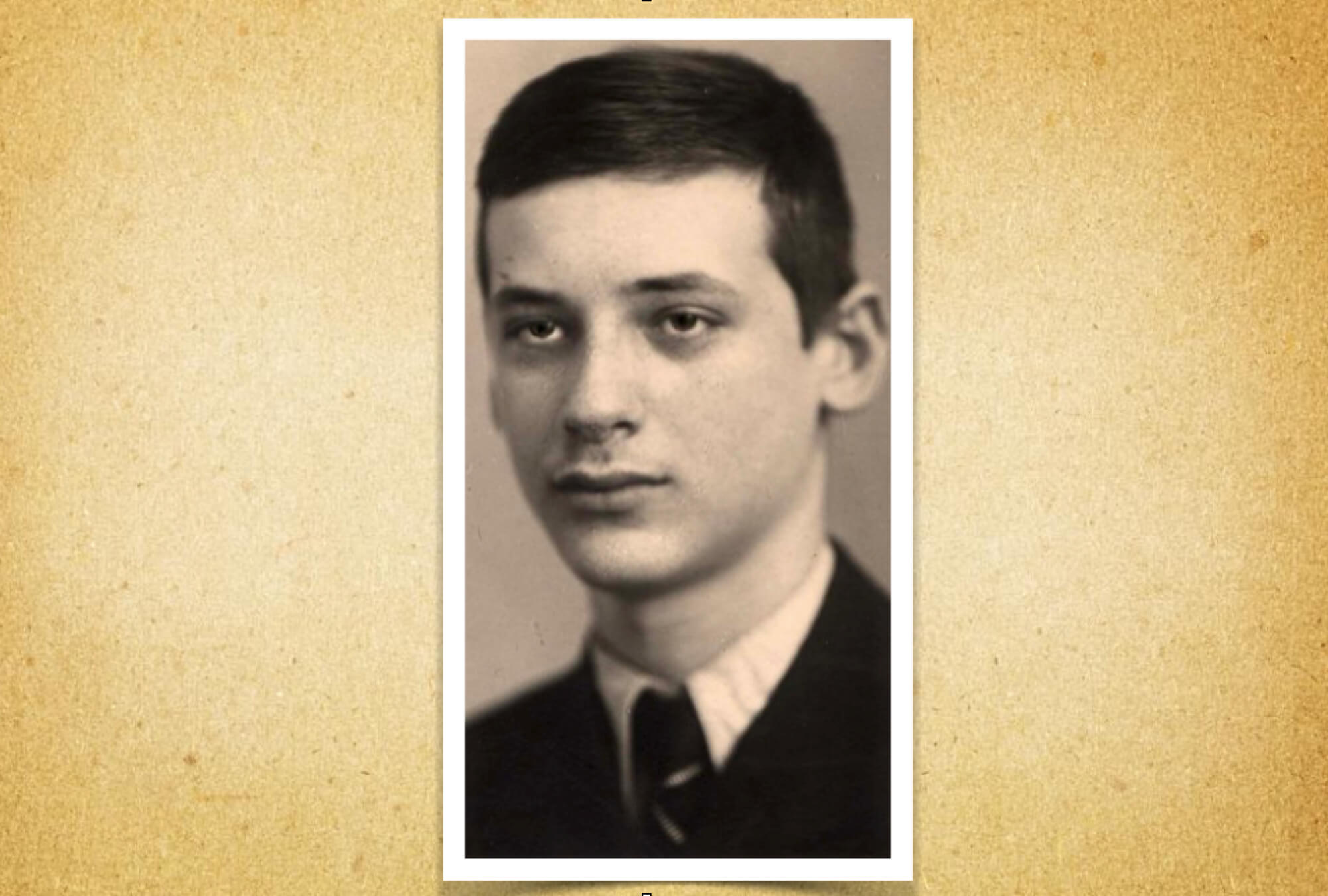

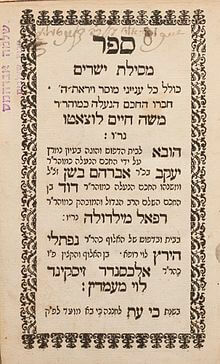

Daniel Lipson, a librarian at the National Library of Israel, read an inscription in a book given to an Austrian-Jewish boy for his bar mitzvah in 1936. Mesillat Yesharim, a volume on Jewish ethics, was confiscated and eventually sent to the NLI with about 35,000 other Nazi-looted books. Lipson’s further research revealed that the boy, David Neuwirth, had been murdered in the Holocaust, but that others in his family had survived.

Devorah Ebbing, who lives in Israel and whose late grandmother was the bar mitzvah boy’s sister, went to the library last year to hold the book in her hands.

“I felt a connection to the great uncle I never knew,” said Ebbing, recalling the day when she was introduced to the book and to the granddaughter of the man who gifted it.

Lipson said other books confiscated by the Nazis can yield information about those their original owners. The library has applied for a grant so that its staff can search its collection, looking for stamps of private collections, personal inscriptions and other signs that a book, which may have rested undisturbed in the NLI for decades, had been stolen by the Nazis during the Holocaust.

The grant, from a source Lipson declined to name because the application is pending, would fund the cataloguing of titles and scanning of book stamps and other markings to create a database for researchers and for those looking for books taken from their families or communities.

A book exodus

The 35,000 books looted by the Nazis and now at the NLI constitute a fraction of the hundreds of thousands shipped from Europe to Israel, mostly in 1949–51, Lipson said. Of those that had been stolen, nearly all came from Jewish-communal libraries, Jewish schools and notable people’s collections, he said. Most titles were not Jewish-themed.

NLI, founded in 1892 as a Jewish cultural repository, distributed the vast majority of the Nazi-looted books it received to libraries across Israel, Lipson said.

The books had reached NLI through Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, an organization established after World War II to reclaim heirless Jewish books seized by the U.S. Army from the Berlin and Frankfurt centers where the Nazis studied the people they sought to annihilate.

There was no master list of the books that reached Israel, so the first stage of Lipson’s project, which concluded last month, entailed building an inventory from individual lists. During World War II, NLI officials began planning to recover the stolen books, which they dubbed “diaspora treasures” — a name that endures.

Stolen books still at NLI are mingled with other holdings throughout the library on the Hebrew University’s Givat Ram campus in Jerusalem. The library will move into a new building nearby later this year.

The bar mitzvah boy

When Lipson first opened Mesillat Yesharim, authored by 18th-century Italian Rabbi Chaim Moshe Luzzatto, he saw the Hebrew message in the inside cover, handwritten on March 12, 1936:

To the nice, persistent, God-fearing boy, David Dov (may his life enlighten us), to mark the celebration of his bar mitzvah, a gift from the S. Schonfeld family.

— Vienna, the Thursday preceding the Shabbat of

[reading the Torah portion of] Ki Tisa 5696

After several months of research on the databases of Yad Vashem, Israel’s central Holocaust memorial and museum, Lipson determined that the bar mitzvah boy was Neuwirth, and the gift giver, Shmuel Shabsai Schonfeld.

In one document, a woman in London, Ilse Ruth Deutsch, attested to the death of Neuwirth, her brother.

Another document stated that he, their parents and two other sisters were transported on a freight train that left Vienna’s Aspangbahnhof station on September 14, 1942, and arrived on September 18 at Maly Trostenets, near Minsk, in present-day Belarus. There, the Nazis’ Schutzpolizei uniformed police shot them — Neuwirth was 19 — and approximately 1,000 other Jews to death at open pits in the Blagovshchina forest.

The Nazis weren’t much interested in saving books ordinary people owned, so it’s unclear how Neuwirth’s book survived, Lipson said.

Deutsch, who died in 2018, told her family that her brother was a friendly boy. But she generally spoke little of the past, said her son, David Deutsch, of London, who is Ebbing’s father.

While his mother likely “would have had no interest” in the discovery of Neuwirth’s bar-mitzvah gift, David Deutsch said, he sees things differently.

The book preserves the memory of “one of the millions of victims who the world would prefer to remain a statistic,” he said. “Every personal story, small or large, brings them to life.”

The book, which NLI retains, “is tangible evidence of who this boy was,” said Debby Spero, Schonfeld’s granddaughter, who attended the gathering the library arranged last year with Neuwirth’s relatives.

“I know how powerful an artifact is,” said Spero, who leads tours at Yad Vashem.

Schonfeld, who like Deutsch escaped the Holocaust by fleeing to England in the late 1930s, was appreciated for buying books as gifts and penning meaningful messages, she said.

Of Schonfeld’s inscription to Neuwirth, Spero said: “My grandfather was the vehicle for rescuing this child from anonymity.”