Canadian government has given $2 million to Ukrainian Canadian groups that celebrate Nazi collaborators

A Forward investigation reveals troubling track record behind apologies and resignation

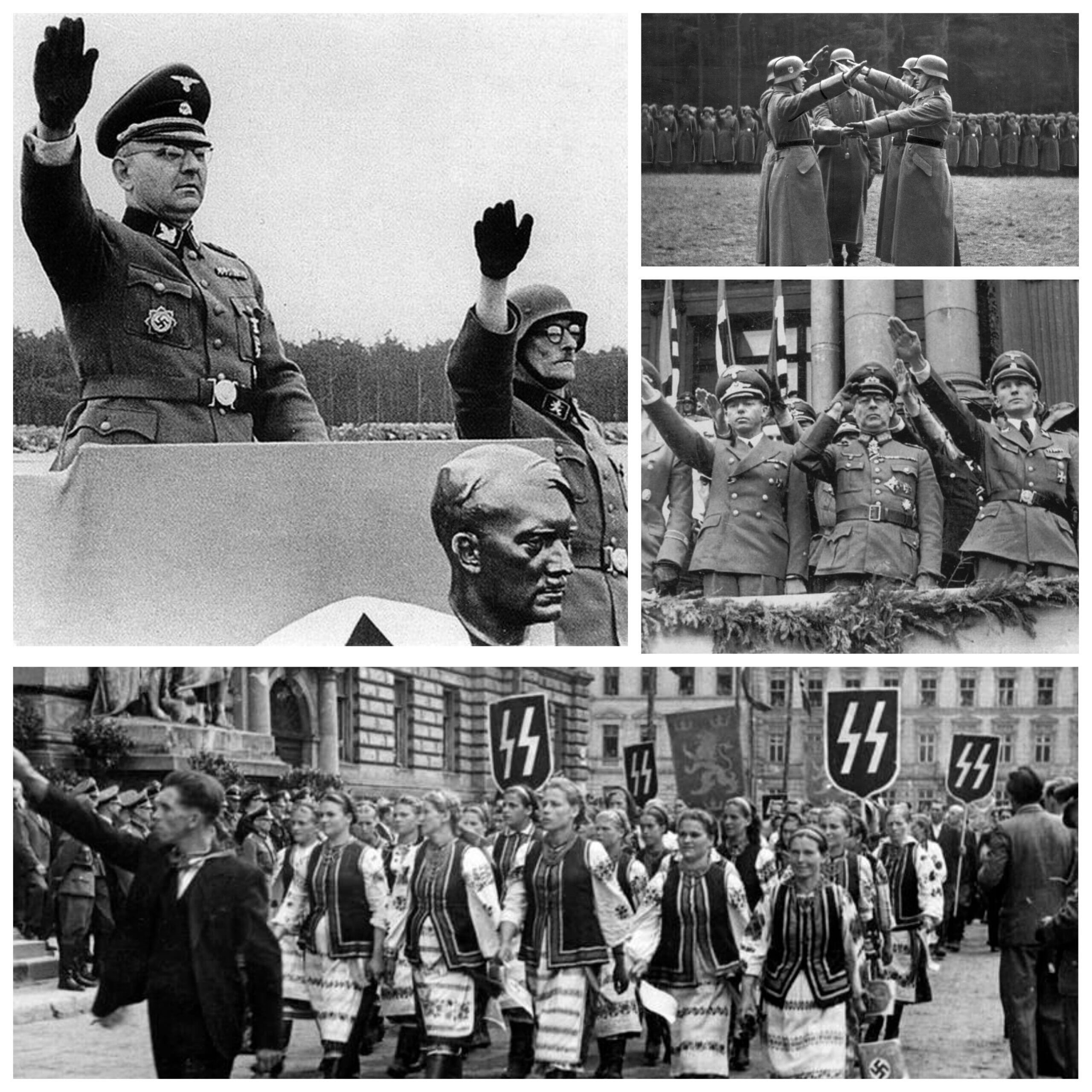

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Canada’s political leaders have expressed shock and shame that their Parliament honored a Ukrainian immigrant who fought in a Nazi unit during World War II. But a Forward investigation found that the Canadian government has given some $2.2 million over the last seven years to at least eight groups that have championed the same unit’s veterans or otherwise lauded Nazi collaborators.

Some of those groups rushed to defend the immigrant, 98-year-old Yaroslav Hunka, and the ovation he received last month, even as it sparked the resignation of the House speaker who invited him to the Parliamentary session and an apology from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Most of the money went to the Ukrainian Canadian Congress, a sprawling umbrella group that has praised Hunka’s unit — known as SS Galichina or Galizien — and defended a monument to it in the Toronto suburb of Oakville. The congress is listed on public records as the recipient of nearly $1.5 million between 2016 and 2022, much of it for translation services for new immigrants.

Then there is the Ukrainian National Federation of Canada, a 40-plus-year-old cultural organization whose logo contains the insignia of a faction of the fascist Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. The group got the equivalent of $140,000 in grants between 2015 and 2022, mainly to provide summer jobs for youth. Last month, its president said of Hunka: “The fact that he was a soldier doesn’t mean he was a Nazi” but conceded that applauding him “maybe wasn’t correct” given the circumstances.

And the New Pathway newspaper, which once said a Canadian Jewish newspaper was fanning “ethnic discord” by calling for the removal of a monument to a Nazi collaborator, received about $68,000 from a fund that supports local publishers. The newspaper also wrote in 2020 that SS Galichina veterans were “subjected to unwarranted attacks labeling them as ‘Nazis’” and that the division was “wrongly accused of ‘Nazism’.”

New Pathway was the only one of the eight entities covered in this article that responded to a request for comment. In an email, the publication’s editorial writer, Marco Levytsky, echoed the characterizations in the 2020 article, saying the unit has “been wrongly labeled with the Nazi brand.”

“They only joined the German forces in order to oppose the Soviet Union, which had killed millions of Ukrainians in the genocidal Holodomor,” he wrote, referring to a state-orchestrated famine. He cited a Sept. 4, 1950 dispatch from the British Foreign Office to Canada’s Department of External Affairs that said the veterans “have never indicated in any way that they are infected with any trace of Nazi ideology.”

The grants to newspapers, youth groups and cultural organizations came from a variety of agencies and programs within the Canadian government, including those responsible for Canadian heritage, social and economic development and public safety. The records are stored on Canada’s main government website, the grants are listed in Canadian dollars but we have converted the amounts to U.S. currency.

About 1.4 million of Canada’s 38 million people have Ukrainian heritage. The organizations that received federal money mostly do things that have no connection to SS Galichina or World War II — many have played important roles in welcoming Ukrainian refugees in the wake of Russia’s invasion of their country last year.

The fact that the groups also have track records of publicly defending Nazi collaborators and Holocaust perpetrators — and that Canada’s government has helped finance them — reflects the complexity of the country’s relationship with Ukraine’s World War II legacy. Moss Robeson, an independent researcher in New York, has been chronicling the financing and activities of Ukrainian Canadian groups for several years in The Maple and the Bandera Lobby Blog, among other places.

More than 2.5 million Ukrainians died fighting against the Germans during the war. However, a tiny minority joined forces with the Third Reich instead.

Hunka was in that minority, as the Forward first reported after the Parliamentary ovation to him during a visit by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Neither he nor his children and grandchildren have responded to requests for comment.

His unit, the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS, which was created in 1943, was equipped and trained by Germany and commanded by SS officers. Footage from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum shows top Third Reich officials attending elaborate recruitment ceremonies for the division. It’s believed responsible for war crimes including the 1944 Huta Pieniacka massacre, where hundreds of Polish villagers were burned alive.

After the war, thousands of men who fought for the Nazis were nonetheless allowed to freely resettle in the West. About 2,000 SS Galichina veterans were welcomed into Canada; thousands of others went to the U.S, the U.K., and Australia.

During the Nuremberg Trials, the International Criminal Tribunal declared the Waffen-SS overall to be a criminal organization responsible for mass atrocities.

But in 1986, a Canadian commission asserted that members of SS Galichina “should not be indicted as a group” and that “mere membership” in the division did not justify prosecution or revocation of citizenship. Jewish groups and many historians have criticized that commission’s work, but it has provided cover for the campaign to recast these veterans as Ukrainian nationalists who battled the Soviet Union.

“Various representative institutions of the Ukrainian minority in Canada lobby to present the soldiers as freedom fighters, saying they got a clean bill of health from the Deschenes Commission and therefore there’s nothing to talk about,” said Efraim Zuroff, director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Jerusalem office. “But the Deschenes Commission was very flawed: it didn’t have the tools and the wherewithal to do a serious investigation of these people.”

Indeed, Levytsky, the editorial writer for New Pathway, cited the Deschenes Commission as having cleared the SS Galichina veterans of any crimes in his email to the Forward on Friday, and noted that Eastern Europe’s World War II history “is most complex.”

“Russian dictator Vladimir Putin has used the “Nazi” label to justify his genocidal war against Ukraine and its courageous Jewish president,” Levytsky added. “Knee-jerk, simplistic reactions to a most complex history serve only to feed his propaganda campaign designed to weaken Western support for Ukraine.”

While the current Russia-Ukraine war has in some quarters heightened this take on Ukrainians who fought with the Nazis during World War II, the Hunka ovation has also led to renewed scrutiny of the Deschenes Commission and SS Galichina veterans generally. For example, Trudeau said he was considering declassifying documents from the commission’s investigation, a marked shift decades of Canada refusing to act on Jewish groups’ calls for the declassification.

And a Polish minister has taken steps to look into Hunka’s extradition for possible war crimes.

Jared McBride, a historian at UCLA, pointed out that the revelations about Canada’s complicity in ignoring or rewriting the past of SS Galichina veterans “has been known to the academic community” since the 1990s.

“There has been a long history of various diasporic organizations in Canada — and not just Ukrainian ones — engaged in obfuscation and at times outright denial of the darker pages of their nation’s history, not just the Holocaust but other events, as well,” McBride said.

What is “extraordinary” about Canada, he added, is that — unlike in the U.S. — when “peer-reviewed academic work laid bare unbiased history of what various groups, military units, and individuals did during the war, there seemed to be no urgency or desire for reflection or reevaluation of relationships with diaspora organizations who refused to accept this reality.”

A history of whitewashing

Long before the Forward exposed Hunka’s service in SS Galichina, Ukrainian groups had erected two monuments to the unit’s veterans.

The one in the Oakville cemetery has a towering pillar bearing the division’s Waffen-SS insignia, which the ADL considers a hate symbol, and which also adorns numerous individual graves nearby. Another, in Edmonton, honors several Ukrainian military units including SS Galichina as “fighters for Ukrainian freedom.”

Members of a white supremacist group, the Active Club, have been making pilgrimages to the monument in recent days, The Globe and Mail reported, leaving flowers, posting pictures of themselves at the sites and thanking the SS unit for protecting Europe from “the Asiatic-Communist pestilence,” a common theme in Third Reich propaganda.

The Ukrainian cultural organizations backed by Canadian government funding have also celebrated other individuals and groups with Nazi ties, including:

- The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, a fascist group which had allied itself with the Nazis and participated in the Holocaust. In 1943, an OUN faction created a paramilitary wing called the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, which historians hold responsible for liquidating Jews and between 70,000 and 100,000 Poles.

- Stephen Bandera, who led a faction of the OUN and is perhaps the best-known symbol of Ukrainian collaboration with the Nazis. Attempts to rebrand Bandera as a freedom fighter who challenged the Soviets have been condemned by the Simon Wiesenthal Center, the World Jewish Congress, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and Israel.

- Yaroslav Stetsko, another OUN leader who wrote in 1941: “I insist on extermination of the Jews and the need to adapt German methods of exterminating Jews in Ukraine.”

- Roman Sukhevych, who was an officer in a German auxiliary police battalion before becoming commander of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army.

A publication called Ukrainian Echo, or Homin Ukrainy, that has produced special editions honoring Bandera, Stetsko and the UPA, was the recipient of about $125,000 in federal funding from Canada over the seven years, the government website shows.

The Ukrainian World Congress, which got three grants totaling about $20,000, celebrated Shukhevych’s birthday in a Facebook post on June 30, 2020, saying he was a “commander in the Nachtigall Battalion,” whose officers participated in proclaiming an independent Ukrainian government. No mention is made that Nachtigall was a Third Reich formation that killed Jews.

Last year, the group posted a birthday message for Shukhevych that aimed to link him to today’s struggle against Russia: “We remember the heroes of all generations who fought for the liberation, freedom and independence of Ukraine.”

And in 2010, the group issued a statement to the European Parliament slamming the notion that Bandera and his branch of the OUN were Nazi collaborators as a “groundless accusation.”

A bust of Shukhevych outside of a Ukrainian youth complex in Edmonton has been at the center of the battle over Canada’s Nazi legacy for the last several years. Attempts to honor Shukhevych have been condemned by the World Jewish Congress, the U.S. State Department, the Simon Wiesenthal Center and Israel.

Edmonton’s Ukrainian Youth Unity Council along with the Ukrainian Youth Association of Canada received nearly $438,000 in government funding. That included about $25,000 to install security cameras at the youth complex after someone wrote “Nazi scum” on the bust in 2019.

Last month, a spokesman for the youth complex told the BBC that Hunka is “a victim of a Russian narrative that has now been successful.”

Meanwhile, the youth association’s website portrays Shukhevych and his comrades as freedom fighters whose legacies had been smeared by Moscow. An archived page of one of its chapters includes photos of children marching with a portrait of Stetsko.

New Pathway, one of the newspapers that also received federal money, had criticized the Alberta Jewish News, which called for the removal of the Shukhevych bust for fueling “the flames of ethnic discord.”

Monuments of controversy

The monuments to SS Galichina in Oakville and Edmonton have generated some debate amid a larger reckoning in Canada — as in the United States — over statues honoring the country’s colonial legacy. On numerous occasions, the Ukrainian Canadian Congress — the umbrella group that got more than $1.4 million in government funds — has defended them.

The group, whose website says it “represents the Canadian Ukrainian community before the people and government of Canada,” wrote a letter in 2020 attacking a journalist who chronicled SS Galichina’s history and record of war crimes in the Ottawa Citizen. The letter accused the reporter of repeating “false narratives originating from the Russian federation” and contended that the article’s description of the pillar as a Nazi monument was “shocking and misleading.”

Three years earlier, the group’s president had, in an interview with the National Post, called the suggestion that SS Galichina fighters were Nazi collaborators “slanderous.”

The same theme is echoed by the Ukrainian Canadian Research & Documentation Centre, which received around $140,000. The group has a page about SS Galichina on its website, presenting its soldiers as men “who fought bravely for the defense and independence of their homeland,” and are unjustly accused by “leftists forces” who “paint the veterans of the Division as Nazi collaborators.”