Romi Gonen, Itay Chen, Kfir Bibas. Every Israeli Jew holds a particular hostage in their heart

They yearn for the release of all 132 remaining in captivity, but focus on individual faces and stories

Hava Ortman, a volunteer at Hostage Square, tries not to look at the faces on the hostage posters she hands out. Having too personal a connect, she said, would be too painful. Photo by Susan Greene

TEL AVIV —When Noam Laskov lets himself hope, it is mainly for a hostage he has never met.

Laskov, who is 15 and a pianist, played Frank Sinatra’s “My Way” in the rain here in Tel Aviv’s Hostage Square this week to honor Romi Gonen, who was abducted from the Supernova Music Festival on Oct. 7. She is 23 and, like Noam, from Kfar Vradim, an industrial town of about 5,500 in Israel’s north.

“She’s the one I’m always thinking of,” said Laskov, who traveled to Tel Aviv with his schoolmates Wednesday to meet with Gonen’s mother.

Noam Laskov, 15, played Frank Sinatra's “My Way” in the rain Wednesday in Tel Aviv. (?️ @Greeneindenver for the @jdforward) pic.twitter.com/m1BRqzgQg7

— Benyamin Cohen (@benyamincohen) January 25, 2024

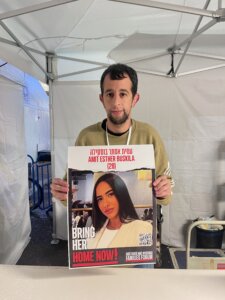

For Ofek Sinvani, a teenager from Ramat Gan, it’s Itay Chen, a 19-year-old soldier taken from Kibbutz Nahal Oz, near the Gaza border. For Tal Schechter, it’s Amit Buskila, a 28-year-old stylist from Tel Aviv — and his best friend since they met on Instagram a dozen years ago.

Every Israeli Jew seems to have a particular hostage among the estimated 132 still in Gaza that they focus on most, that they relate to, that they pray for. Of course they yearn for the release of the whole group; this week, hostage families and hundreds of other protesters blocked traffic in Tel Aviv and a border crossing into Gaza in order to block humanitarian aid from entering the enclave. Relatives of those remaining in captivity also stormed a Knesset session, screaming at lawmakers, “You will not sit here while our children die.”

But as Israel’s war against Hamas, the terror group holding the hostages, drags into its 111th day, I have been struck as I’ve spoken to Israeli Jews at the way many of them hold in their hearts a single name, face and story among the sea represented on the ubiquitous “Kidnapped!” posters in every neighborhood.

“I think of her always, everywhere, even in the shower,” Schechter said of Buskila. “I think, ‘Why am I showering because she can’t shower? She can’t even shower or see light.”

Schechter said he was supposed to go with Buskila to the desert rave on Oct. 6, but at the last minute sold his ticket to May Naim, 24, who was murdered the next morning around the time Hamas terrorists abducted their friend. Guilt and anxiety paralyze him, especially at night. He needs a prescription to sleep.

Three times each week, Schechter is in Hostage Square handing out posters of hostages, including ones of his friend, to keep up the pressure for their release.

“The pain of it,” he told me. “Every day. Just pain.”

Like Schechter, Sinvani, the 17-year-old from Ramat Gan, has a real personal connection with his hostage. Chen was a guide and mentor in the younger man’s youth group.

“He listened well. He inspired me,” Sinvani said. “It is an honor to know him.”

But for Raziel Steinerman, an American tourist visiting Hostage Square this week, the connection is random. At the pro-Israel rally in Washington in November, someone handed him a poster of Liri Albag, an 18-year-old soldier abducted from the Israel Defense Force’s base at Nahal Oz. He took it home to Pennsylvania and placed it on a chair at his family’s dining table. The image of Albag, pink-lipped and wearing a brown cap, has been there every Shabbat since, as if she’s part of his family.

“We’re not taking her down from that chair until she’s released,” Steinerman said.

Hava Ortman, 72, also volunteers at Hostage Square, but deliberately tries not to focus on the faces on the posters she hands out to visitors.

“I distance myself from them and don’t want to connect with any of them too personally so it hurts less,” said Ortman, who immigrated to Israel from Poland at age 5, and now lives in Givatayim, a city of 61,000 east of Tel Aviv. She is not optimistic about their release.

“Of course I hope,” she told me. “I hope, I hope. I don’t know the future. But it won’t be soon, I don’t believe.”

When Liah Lev lets herself hope, it is largely for a boy in a baby picture. Lev is 17, a high school senior who babysits. The boy is redhead Kfir Bibas, the youngest among the more than 200 hostages Hamas took on Oct. 7, whose first birthday was marked last week by outraged Jews around the world.

In the picture, Kfir is wearing a gray and white onesie, grasping a stuffed animal and grinning, toothless and delighted, at whoever was holding the camera.

“I’m pulling for him. How could you not?” Lev said. “He’s my favorite hostage.”

She and her friend Lia Shavav, 18, said they have memorized the faces and stories of hostages not just out of curiosity or concern, but also as a way to lighten the burden for hostage families and keep them from having to endure the crisis alone.

Both young women switched between present and past tenses when talking about those still in captivity. They said that’s because growing up in Israel comes with the knowledge that crises like these don’t always end well.

Lev mentioned Ron Arad, an IDF soldier who has been missing since 1986, when he is believed to have been captured in Lebanon. Likewise, she lowered her voice and sighed, little Kfir may not see freedom any time soon.

“We’re teenagers and we want to be hopeful,” Shavav added. “But we live here. We’ve been educated — and know the situation. We know that some won’t come back at all.”