Come ’Round

Ed Rheingold writes from Evanston, Ill.:

“Challah bread,” of course, is generally pronounced by non-Jews as “hallah bread,” and sometimes even as “holly bread,” and though I have yet to hear anyone say “tshallah bread” or “kallah bread,” the silliness of spelling the word with a “ch” is obvious. Let’s straight-aitch our English h.et-words and have done with it.

Mr. Rheingold continues:

I am afraid that the rabbi is right — or at least more right than Mr. Rheingold, since it is difficult to determine whether the Hebrew root h.-l-l, from which h.allah and m’h.olot derive, originally had to do with roundness and then also came to indicate hollowness, or originally had to do with hollowness and then also came to indicate roundness. Consider these additional biblical and rabbinic words, all formed from the same root: h.alil, a flute or shepherd’s pipe (i.e., a hollow — but also round — reed); h.alul, hollow; h.ol, sand (probably because it is composed of round grains); h.alal, empty space or hole; h.ol again, profane or “emptied” of its sacredness; h.ulyah, a link in a chain, the shaft of a well, a vertebra; h.alal again, a man killed in battle (that is, someone whose body has been pierced and hollowed by wounds); h.alh.olet, rectum; h.alon, a window or open space in a wall; la’h.ul, to come about or fall on a certain date — in other words, to recur each time the year “comes ‘round” again; and le’h.ailh.el, to penetrate or drip through something. “Challah bread” originally was called h.allah in Hebrew because it was baked — as it sometimes still is — in the form of a round loaf.

Mr. Rheingold’s mistaken belief that the root meaning of h.allah is “portion” may come from his knowledge of the Hebrew expression hafrashat h.allah, or from its Yiddish translation nemn khaleh, “taking hallah,” which refers to the custom, still practiced by many observant Jews, of taking a small piece or portion of dough before baking bread and burning it in remembrance of the bread-offering made to the priests in the Temple in ancient times. This, however, is a secondary meaning of h.allah.

The typical Eastern European hallah, of course, was not round but oval. What made a hallah a hallah, as far as most Ashkenazi Jews were concerned, was not its shape but its egg-enriched dough, its braided form and its ritual use for the hamotzi blessing on Sabbaths and holidays. There were parts of Eastern Europe in which, when a hallah was round, it was given a special name, such as rudish in parts of southern Poland and beygel-khaleh in much of Belarus.

Indeed, the different terms for hallahs among Ashkenazi Jews went far beyond this and included such variations as berkhes or barkhes, koilitsh, shtritsl, datsher, kitke, bukhte and shabbes-vek. For the most part, these words were regional and did not all coexist in the same areas. Barkhes and dacher, for instance (both from the biblical verse birkas adonai hi ta’ashir, “It is the blessing of the Lord that brings wealth,” commonly engraved on hallah-cutting knives), were limited largely to the Jews of Germany; shtritsl was used by some Polish Jews; koilitsh was common from Poland eastward, from Latvia in the north to Romania in the south; kitke was confined to Latvia, Lithuania and northwestern Russia. Moreover, even within the same overall region, the same word did not always designate the same bread. A koilitsh, for example, was round in some towns and villages, and not in others; braided in some places but not in all; sometimes a roll, pastry or yeast cake; and sometimes merely the crust at the hallah’s end. A kitke could be an ordinary hallah, an especially large hallah, or the braid on top of a hallah. It was only in America that all these terms disappeared except for “hallah” itself, the only one of them that was known to Jews everywhere.

As for the Hebrew root h.-l-l, it continues to lead an active life. Among its 20th-century creations are h.iloni, “secular” (from h.ol in the sense of “profane” or “mundane”) and h.alalit, “spaceship.” It has given us a lot of words, of which one meaning “portion,” alas, is not one.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected].

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

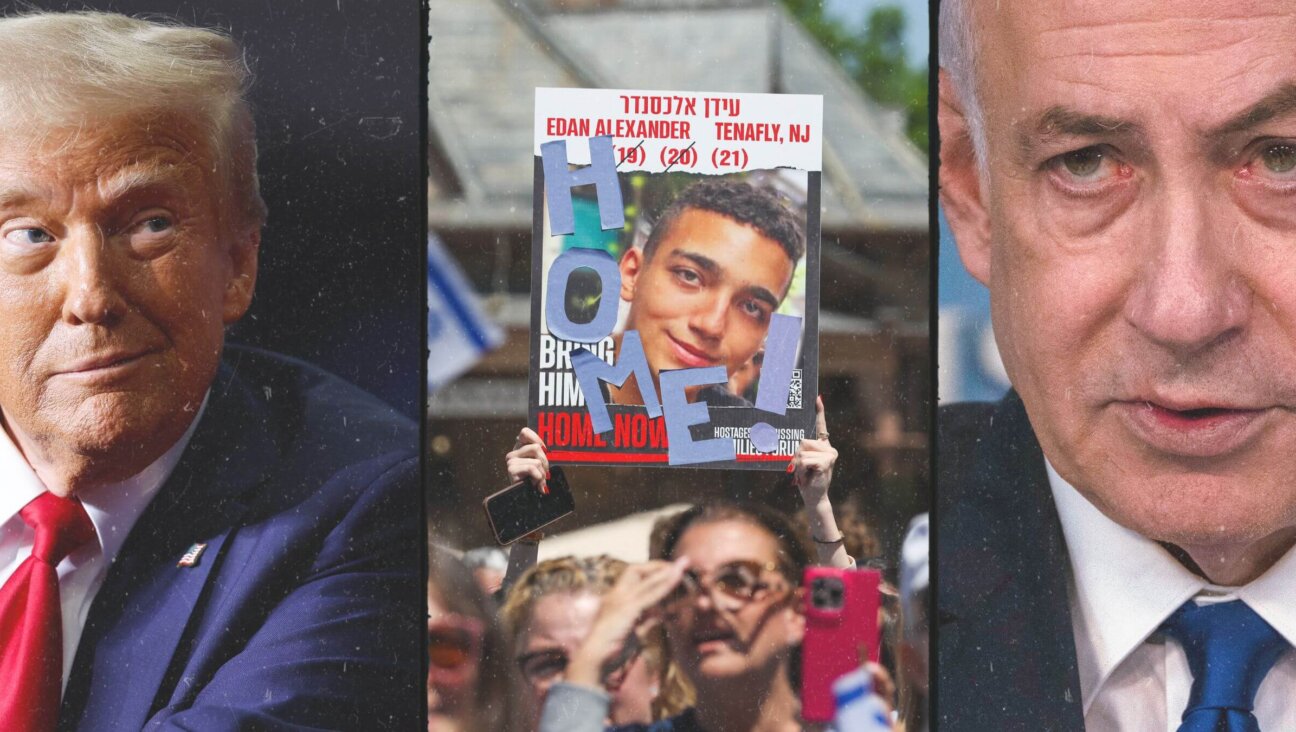

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Opinion Despite Netanyahu, Edan Alexander is finally free

-

Opinion A judge just released another pro-Palestinian activist. Here’s why that’s good for the Jews

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.