24 hours on Israel’s northern front as clashes with Hezbollah intensify

Meet the holdouts who’ve refused to leave a border city under constant fire

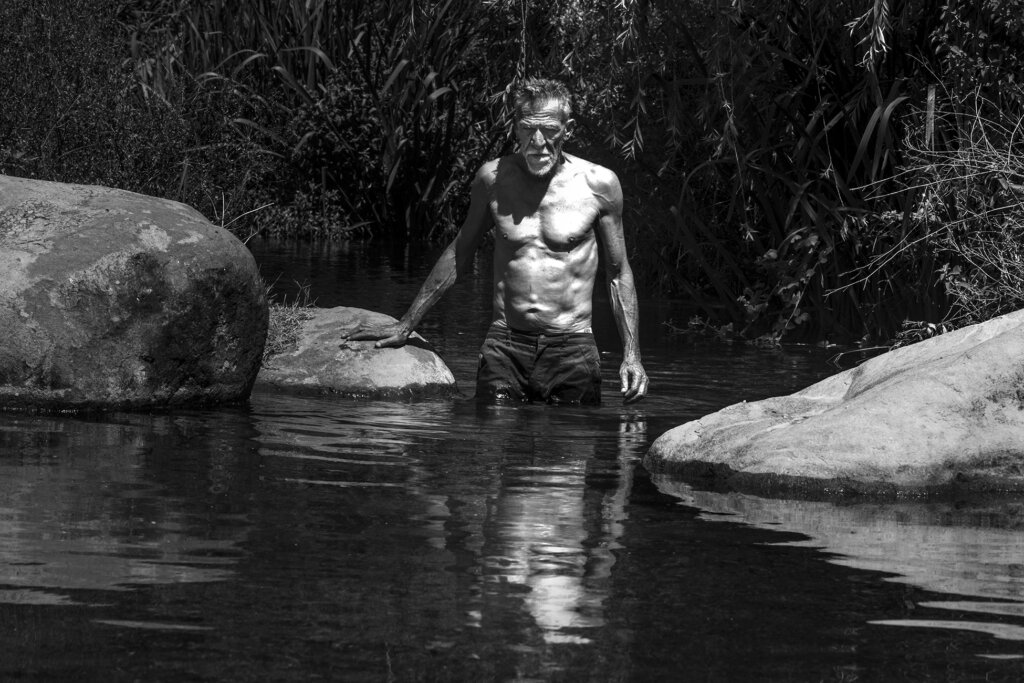

David Kamri was home when a Hezbollah rocket nearly totaled his house in Kiryat Shmona. He has no plans to leave. Photo by Rina Castelnuovo

KIRYAT SHMONA, Israel – For years, residents of this town a mile from Lebanon have kept fragments of Katyusha rockets fired from across the border in their china cabinets or on their keychains, reminders of the ongoing danger Israel faces from its neighbor.

The hard-headed few who have stayed in Kiryat Shmona since Oct. 7 have in recent weeks been adding new tokens of their survival: pieces of anti-tank missiles and Burkan rockets fired by the Lebanese Shiite militia Hezbollah that, in some cases, have mangled their cars or leveled their homes.

These scraps, and the stories locals are telling about them, are at once emblems of Israelis’ resilience and evidence of what many see as the government’s failure to do more to keep them and the Upper Galilee safe.

Some 56,000 Northern Israelis evacuated their homes after the Hamas terror attack and the war it spawned in Gaza, as Hezbollah intensified its strikes. That included nearly all of this city’s 24,000 residents.

Some fled to family or friends, others to state-funded hotel rooms, expecting to be gone a month or two. Most have not returned.

Kiryat Shmona, Israel’s northernmost city, has become a shell of itself — not flattened like Gaza, but bruised and empty and anxious. Hezbollah assaults have pocked walls and shattered windows of houses and apartment complexes throughout town. Synagogues, shopping centers and most schools have been shut down since the fall. Playgrounds, parks and local orchards are charred by fires sparked by the missiles.

The estimated 2,000 residents who’ve either stayed in the city or returned to it despite admonitions by its mayor and the military face growing risk as both Israel and Hezbollah have been striking more frequently and farther across the border in recent days and weeks. The Israel Defense Forces has sounded more than 1,050 red alerts about Hezbollah attacks in the first half of June, compared to an average of 290 red alerts every two weeks since October, IDF data shows.

Since October, Hezbollah rockets, missiles and drones have killed at least 27 Israelis, according to the military. Airstrikes, drone attacks and missiles fired by the IDF, meanwhile, have killed at least 375 people in southern Lebanon, reports the Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center; about 94,000 residents on the Lebanese side of the border have evacuated their homes.

Hezbollah, which like Hamas is backed by Iran, has vowed to continue its attacks until Israel ends its war on Hamas. Israel’s war cabinet, in turn, has said victory in Gaza partly would mean ensuring northern evacuees a safe return home.

In the meantime, Israel has over the past weeks deployed tens of thousands more soldiers to the north, preparing for the possibility of a full-fledged war with Hezbollah, whose arsenal makes Hamas’ stockpile look like matchsticks.

Someone recently placed a sign at the feet of a Lion of Judah sculpture on Kiryat Shmona’s north side that reads: “S.O.S. We are still here.”

That “we,” I learned on an overnight reporting trip here this week, consists mainly of local men too old for reserve duty who stayed to fight fires, tend orchards, care for livestock, or help neighbors whose health conditions kept them from evacuating. Others have refused to leave out of patriotism, defiance or inertia.

All were eager to talk about life here in what has become Israel’s loneliest city, and about the small-scale war that each day is intensifying around them.

Joining me on the journey was Rina Castelnuovo, an award-winning Israeli photojournalist and documentarian who has visited the north innumerable times over the decades. Here are some scenes from our visit.

‘Welcome to the north’

We arrived 10 minutes early for our meeting with Prosper Azran, who served as Kiryat Shmona’s mayor from 1983 to 1997 and has been criticizing the government for scaring local residents out of town. His neighborhood was struck 12 times in the three days before our visit, and he’d replaced his shattered windows twice in two weeks.

A TV crew was interviewing his 10-year-old grandson, Nehoray, in the living room when we rang the doorbell. The producer asked the boy what it’s like living in a town that his classmates and other friends have fled.

“Mostly fun, I guess,” he answered, “except for the explosions.”

The third-grader led all of us journalists out of his grandfather’s home, into the backyard of the house behind it, where he lives with his parents. He was showing us a cage full of lovebirds he raises — more than 250 them, in all manner of colors — when a siren blared warning of an incoming assault from Lebanon.

The IDF sounds the alarm whenever it detects a Hezbollah rocket, giving residents in these parts only seconds to find shelter while the Iron Dome missile defense system is deployed to intercept it.

Nehoray took off running, motioning for all of us to follow him back to his grandfather’s house — through the kitchen, down the hallway and into the old man’s bedroom. It isn’t a safe room by Israeli standards, but safe enough, Azran said later, to have kept him alive through what he estimates have been thousands of cross-border attacks since the late 1970s.

He put his arm around me for protection as we waited for an explosion or the siren to stop.

“Welcome to the north,” he said.

“Don’t worry,” he assured both me and Nehoray, who was rocking somewhat nervously on the floor. “We’re not going to let each other die.”

‘If we don’t do anything, we’re next’

On a street where several rockets have landed, a high rise is deserted, but standing. A badly damaged Israeli army Humvee sits, abandoned, across the empty street. Around the corner we find the only business still open in the neighborhood — a small gym where we chat with Rimon Arad before his workout.

Arad, who is 17, fled his nearby farming community, She’ar Yashuv, with his mother and younger siblings to a hotel farther south in October. He returned home a few months later to keep his army-reservist father company and finish his senior year of high school.

He said that only a small fraction of students show up, and that school is open for three rather than eight hours a day.

Arad will graduate this summer without having read all of the books or learned all the things he was meant to this school year. Shelling and wildfires keep knocking out his internet. And so he has been practicing jazz guitar, teaching himself how to brew beer, and cooking for his dad, which can be tricky, he said, “because the only market still open has lots of food that’s expired.”

Before starting his bench presses, he wanted Rina and me to know that rockets have been raining down on She’ar Yashuv, the village where his mom was born and where he plans to spend his life farming and raising his own family.

“There is a war here, even if they don’t call it a war,” he said, urging me to write that only a wider battle with Hezbollah will — if Israel prevails — keep this area safe. “People are trying to kill us.”

Ouri Hayon, a 44-year-old pizzeria owner and part of the security team at his local kibbutz, echoed Arad’s support for, as he put it, “a full war — something big that could stop Hezbollah” and keep its fighters from invading Northern Israel like Hamas invaded the south in October.

“We believe if we don’t do anything, we’re next,” Hayon said. “It’s Lebanon here right now. They control the rules.”

But he and others know that this rural, lightly populated corner of Israel has little political power, and that what happens with Hezbollah will be decided far away, in Jerusalem and even Washington.

“It’s brutal, just sitting here, powerless,” he said, then headed into the gym to lift weights.

‘Zionists don’t run away’

Chris Coyle nursed some beers outside Baguette Shlomi, the only falafel joint that seemed to be open, as he eavesdropped on a few of my conversations.

“You want a story?” he called over from his table. “I’ll give you stories. Got a million of them.”

Coyle, 51 and from Scotland, fought for Great Britain in the first Gulf War and suffers from post-combat trauma. He moved to Israel in 2000 for a woman he later married, had two children with, and divorced. He lost his job installing fiber optics at a nearby kibbutz when it cleared out in October.

He told us that his Honda Civic was totaled by one missile and his apartment windows were blown out by another in the same barrage a month ago while he was home watching Star Wars.

“I’m a Scottish Atheist and not even Jewish, yet they’re still trying to kill me,” he said of Hezbollah, half laughing, half crying, and relishing having an audience.

He has stayed in town even though he can’t find work here and his now-ex wife and two teenagers are living in a hotel in Tiberias, about an hour south. I asked why.

“Because I will not run from terrorism,” he said. “I fought too hard for too many years to be a good father, a good friend to my ex-wife, a good man in my community. I will not run, because if you run from terrorism, the terrorists win.”

Coyle’s cab showed up to take him home, and he introduced his driver, a 55-year-old Druze named Amasha Hussein, who told me business is down 80% since October even though he’s pretty sure his is the only taxi left in Kiryat Shmona.

Hussein took us to Coyle’s apartment complex, where five of 270 residents are still living. Most of its windows have been shattered and boarded up, and most of its walls are scarred by shrapnel. Coyle pointed out the apartment of one elderly neighbor he fetches groceries for every day because she’s afraid to go outside. He also pointed out his own place on the fourth floor — too many flights of stairs up to make it down to the bomb shelter outside the building in time to protect himself when the sirens blare.

“There’s no time even to put my helmet and flak jacket on, so I basically just sit there thinking ‘please, don’t let this be the end of me,’” he said.

Coyle asked Hussein to drive to a house around the corner where, a month ago, a Burkan rocket totaled two cars, blew out the kitchen, most of the patio, two doorways and several walls. He assumed nobody would be there.

But as we looked around, we noticed David Kamri sitting shirtless in his dark kitchen, glass shards and dirty dishes everywhere, and containers of yogurt rotted in the broken refrigerator whose door is too twisted to close.

Kamri, 71, told us he was hanging out on his patio when the rocket hit and the tin roof collapsed on top of him.

“I got very, very lucky that I’m still whole, if you know what I mean,” he said.

The retired contractor was irked when I asked why he doesn’t go somewhere cleaner and more structurally sound.

“Because I’m a Zionist,” he said. “Zionists don’t run away.”

‘You think about it every day’

Coyle, with time on his hands and yearning for company, offered to show us a nearby kibbutz that borders directly onto Lebanon. He said he knew a road up a mountain where Hezbollah fighters wouldn’t be able to spot us.

Rina drove as he directed us past a checkpoint where the military has built concrete walls to obstruct Hezbollah’s view of the road from nearby ridges.

“Hey boys, cheers,” Coyle yelled to the gaggle of soldiers posted there, raising his beer can.

We wound our way up the mountain, past vineyards and apple orchards, around a cattle pasture, and through kiwi bushes and pomegranate and avocado trees to Kibbutz Malkiya, whose population of 445 residents has since October plummeted to 25, plus a few farmhands from Thailand who stayed to work the fields.

About 150 soldiers rolled into the kibbutz after Oct. 7, resident Dean Sweetland said. In March, the kibbutz council asked them to leave, concerned the military presence only made Malkiya more of a target.

But shelling hasn’t let up much, and now only the kibbutzniks are left to put out the fires sparked by the attacks on the dry, mountainous landscape.

Sweetland, a British-Israeli landscaper who has lived on Malkiya for eight years, said he spends at least some part of most days using garden hoses and leaf blowers to extinguish fires set off by shelling. On his terrace overlooking the Hula Valley, he unwrapped a kitchen towel to show us rocket fragments that landed at a neighbor’s place the day before. The attack killed a cat sleeping on the couch.

In a community that didn’t lock its doors before October, Sweetland said, he has been sleeping in his safe room for several months, fearing that if Hezbollah fighters come through the border about 100 meters away, “there would be no defense.”

“You think about it every day, from the time you wake up to the time you go to bed,” he said.

From this high on the mountain, Sweetland can see rockets heading northeast toward Kiryat Shmona before sirens sound there, if they sound at all. He phones Coyle, his drinking buddy, to warn him: “Get your head down.”

Like Coyle, Sweetland, who is 53, moved to Israel for love. His wife and daughter, too, have evacuated. Though many Malkiya residents say they no longer plan to return to the kibbutz, he sees his own future here in the house he has been building for his family.

“I have to die somewhere, why not do it protecting this land that is not my own, but I’ve come to love?” he asked. “Why not do it protecting the people of the North whose government has forgotten them?”’

The Englishman and Scot said their goodbyes, and Coyle drove with us back down the mountain and past the IDF checkpoint. A fresh beer in hand, he once again toasted the soldiers out the car window.

“Bye guys,” he hollered. “Love you! Love you!”

‘I end up talking to my five dogs’

When your city feels like a dartboard for Hezbollah missiles, it’s hard to predict where it’s safe.

“You can overthink it,” said Naftali Albiliya, 57.

A local hotel booker who lost his job when tourism dried up because of the war, he evacuated in October to Tel Aviv. But he couldn’t stand the fighting he heard among evacuees at his hotel, or seeing news reports on TV about his abandoned hometown. He moved back over the winter to volunteer delivering food, mostly to older residents who for various physical and mental health reasons didn’t evacuate.

Albiliya, wearing a “Whatever, Whatever, Whatever” T-shirt, told us that his house was totaled by a suicide drone a month ago. A week later, he said, while he was driving, one missile struck the road behind him, another next to him, and a third in front of him. He stopped, laid on the pavement, and told himself he was OK until he believed it enough to get back in and drive away.

“It took me five hours to calm down,” he said.

We met at a gas station just off Kiryat Shmona’s main drag. He acknowledged that proximity to gas pumps is risky when rockets are falling, but said he likes the coffee.

His friend, a farmer named Eliezer Haziza, joined us, and as the two smoked they agreed that a full-out war with Hezbollah is inevitable.

“From the biblical times, they hate us and we hate them,” Albiliya said. “That will never end.”

Haziza, though, seemed unwilling to give up on the prospect of peace in a place where he has spent most of his 63 years growing pears and raising sheep. “Their way is different, but it doesn’t mean we need to hate them,” he countered.

The men commiserated about their mothers constantly nudging them to leave Kiryat Shmona for somewhere safer. They talked about elderly locals whose kids and grandkids aren’t visiting like they used to. They spoke of a few old-timers who died recently — maybe of loneliness, they surmised — and who were buried in the middle of the night, when cemeteries were less likely to be hit by a rocket.

They also spoke of their own loneliness, and the dearth of women left in town.

“You must talk to someone,” Haziza said. “I end up talking to my five dogs. You wouldn’t believe the stuff I tell them.”

It was 9 a.m., time for the morning prayer service at the Chabad house, whose underground bomb-shelter-slash-boxing-ring Rina and I had slept in the night before after a drone attack.

Nine men showed up, including Haziza and Albiliya. One shy of the quorum Jewish law requires for group prayer. A flurry of phone calls ensued by men already wrapped in prayer shawls, including the rabbi himself, imploring any man who answered to drop everything and come pray. A few came rushing in shortly after. Among them was a uniformed border patrol officer who was greeted with an embrace by the rabbi and given the honor of holding the Torah.

Israeli fighter jets soared overhead and weapons exploded in the distant hills as the men prayed.

Afterward, we followed Albiliya through a neighborhood to a pool of river water known as the Kurdish Spring. It served as the mikvah (ritual bath) for the city’s first Jewish settlers in 1949. Blue dragonflies and red ones flitted around, landing on the leaves and water.

Haziza met up with us there, and the men recalled swimming in the river as boys and how busy it used to get, before Oct. 7, in summer. Each lamented how many years had gone by since they had taken the time to come, if only to cool their feet in the water.

These days, with no kids in town, they have the swimming hole to themselves.

Both went all in, down where there is no smell of smoke or ammunition and no red alerts bleeping on cell phones whose GPS — intentionally scrambled in these parts by IDF — showed us all at the Beirut-Rafic Al Hariri International Airport rather than the finger of the Galilee.

“How marvelous to get back here,” Haziza said while drying off.