You Call That a Man?

Marvin Friedman writes from San Francisco:

Indeed it was the victims of the concentration camps whom Levi was referring to in his title, which means “If this is a man.” He took the phrase from a poem of his that he prefaced to the book and that begins: “You who live safe/ In your warm houses,/ You who find, returning in the evening,/ Hot food and friendly faces:/ Consider if this is a man/ Who works in the mud/ Who does not know peace/ Who fights for a scrap of bread/ Who dies because of a yes or a no./ Consider if this is a woman,/ Without hair and without name/ With no more strength to remember,/ Her eyes empty and her womb cold/ Like a frog in winter.”

Oykh mir a mentsh would thus not make a fitting Yiddish title for Levi’s book. Nor would it have made one had Se questo è un uumo referred to the perpetrators of the Nazi genocide, since its tone of sarcasm, as Mr. Friedman correctly calls it, is inappropriate for the monstrousness of Auschwitz. One can only imagine such an expression being used for a Nazi murderer in a specific conversational context, such as:

Sam: “Hitler may have been a monster, but he was a nice man to some people.”

Max: “Oykh mir a mentsh!”

Max’s response — literally, “Also to me a man!” — might be translated as “You call that a man?” It would take a longer paraphrase, however, to transmit its full flavor, which is more like, “If you ask me, it’s a sad comment on humanity when you call Hitler a man.” As Mr. Friedman points out, mir, the dative form of the first-person pronoun, has the same function here as it does in folg mir a gang, namely, to identify the phrase it belongs to as the opinion of its speaker. It’s a way of saying, “As far as I’m concerned” or, “The way I feel about it is….”

Oykh mir a followed by a noun — one can also drop the mir and just say oykh a — is thus an expression that can be handily used in regard to practically anything. For example:

“What’s that you’re reading?”

“Oykh mir a bukh!”

Meaning: “What I’m reading is supposed to be a book, but frankly it gives books a bad name.”

Or:

“My daughter has just moved to Luxembourg.”

“Oykh mir a medineh!”

That is: “Luxembourg? I guess that’s some people’s idea of a country!”

As for Primo Levi’s “Se Questo è un Uomo,” its first English edition, which appeared in Great Britain in 1958, was actually published as “If This is a Man.” The title was changed to “Survival in Auschwitz” by the book’s American publisher when it was reissued in 1993, a commercially motivated move that many of its admirers found objectionable. As Philip Roth put it in a conversation with Levi, a chemist by profession, in lamenting the abandonment of the original title: “The description and analysis of your atrocious memories of [Auschwitz] is governed, very precisely, by a quantitative concern for the ways in which a man can be transformed or broken down… like a substance decomposing in a chemical reaction.”

And yet Levi himself chose “Se Questo è un Uomo” at the last moment, his working title for the book until then having been “I Sommersi e i Salvati,” “The Drowned and the Saved,” an allusion to a line from Dante’s “Inferno.” (In the end this was used as a chapter title in “Survival in Auschwitz” and, again, as the title of Levi’s last book, completed shortly before his suicide in 1987.) He was a writer fond of literary allusions. There is a striking one in the second half of the poem prefaced to “Survival in Auschwitz,” which continues:

“Meditate that this came about:/ I commend these words to you./ Carve them in your hearts/ At home, in the street,/ Going to bed, rising:/ Repeat them to your children,/ Or may your house fall apart,/ May illness impede you,/ May your children turn their faces from you.”

Many of you will hear in these lines an echo of the Shema Yisra’el prayer, taken from the book of Deuteronomy: “Hear O Israel…. these words which I command thee this day shall be in thine heart; and thou shalt teach them diligently unto thy children, and shalt talk of them when thou sittest in thine house, and when thou walkest by the way, and when thou liest down, and when thou risest up.” Dante and the Shema were both equally part of Levi’s world as an Italian Jew.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected].

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

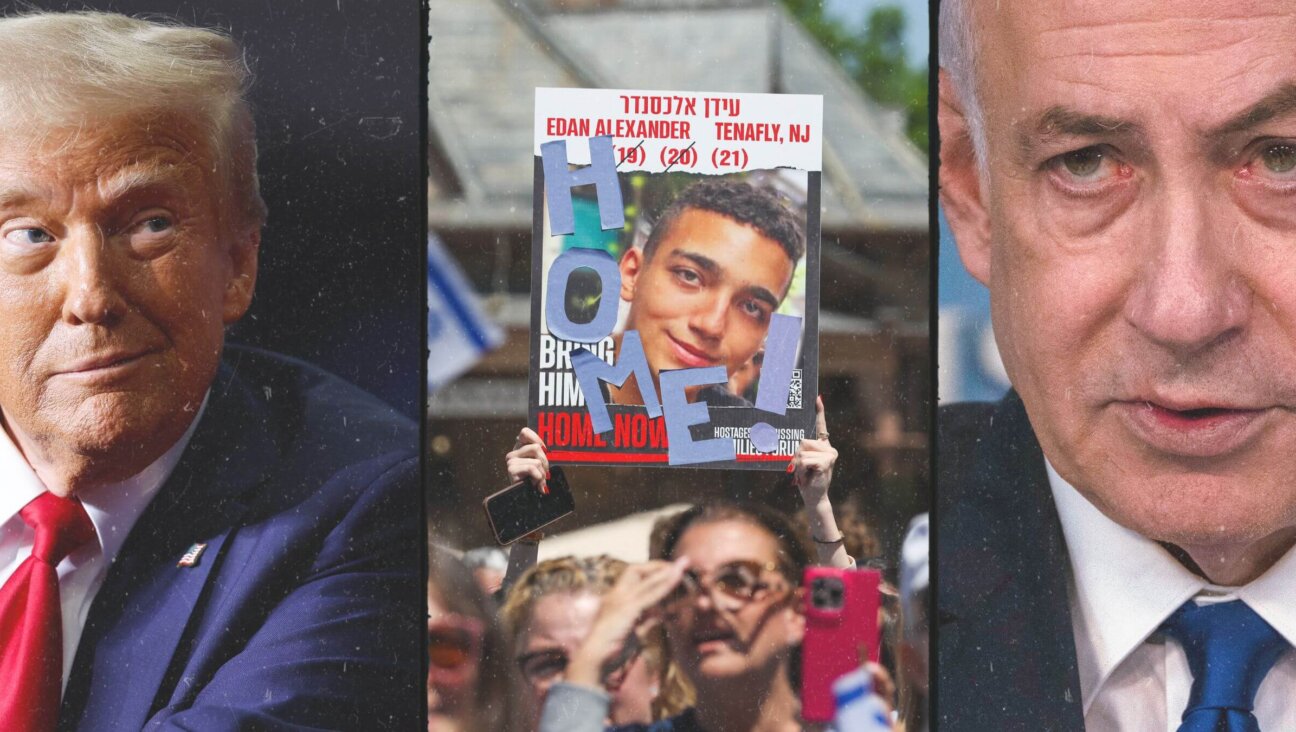

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Opinion Despite Netanyahu, Edan Alexander is finally free

-

Opinion A judge just released another pro-Palestinian activist. Here’s why that’s good for the Jews

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.