‘Do you have the Torahs?’ Synagogue races LA wildfire to rescue its past and future

The Pasadena Jewish Temple and Center is one of 3 synagogues in the path of the Eaton Fire

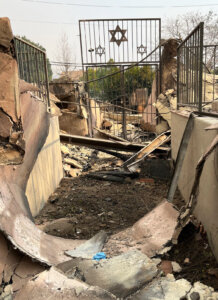

The Pasadena Jewish Temple and Center burns during the wildfire in Pasadena, California on January 7. Photo by Josh Edelson/AFP via Getty Images

Cantor Ruth Berman Harris searched for her husband through the thick smoke that engulfed the Pasadena Jewish Temple and Center. Laurence Harris had been beside her just moments before, but now, as flames closed in and the air grew heavier, he was nowhere in sight.

“Do you have the Torahs?” she shouted, her voice slicing through the chaos, trying to find him amid the suffocating darkness.

And then, there he was. Emerging through the smoke, almost surreal in his calm, carrying one of the synagogue’s 13 Torahs — a Sephardic scroll, heavier than the rest, encased in silver etched with the patterns of a long-lost homeland. It had been donated by a congregant who fled Iran, a piece of history held in trembling hands.

Then the power went out. The fire, a beast consuming Los Angeles, roared closer. Joined by the synagogue president, Jack Singer, and custodian Robert Brown Jr., the couple dashed outside. “Ashes were falling in the parking lot,” she recalled Wednesday morning.

They worked quickly, loading the Torahs into two cars — a white Subaru Outback and a gray Volkswagen Tiguan. By 8 p.m., they were gone, leaving behind their synagogue, their history, their sanctuary. By night’s end, the flames would claim it all.

‘It’s like losing your home’

The Pasadena Jewish Temple and Center stood for over a century, its campus a sanctuary of faith and history in a community nestled just beyond the urban sprawl of Los Angeles. By Tuesday night, it was one of more than 1,000 buildings reduced to ash as wildfires, fed by hurricane-force winds and parched conditions, raged with a vengeance across Southern California. The flames spared nothing, devouring three buildings on the campus, including the B’nai Simcha Community Preschool, where 45 children once laughed and learned.

“It’s like losing your home,” said Jack Singer, the shul’s president, whose family has been members for nearly half a century. He said that the local interfaith community is strong, and he has already received offers from churches to host them. Yet even amid the devastation, his resolve was unshaken. “We are definitely going to rebuild. We will have a PJTC again.”

Nearby, Kehillat Israel and Chabad of Pacific Palisades were evacuated but remain standing, at least for now. For a community still counting its losses, the survival of these sacred spaces offered a glimmer of hope. But the fires showed no sign of relenting, their fury intensified by strained water supplies and unyielding winds — a stark reminder that, for Pasadena and its people, the worst may still lie ahead.

A synagogue without walls, inspired by the mishkan

The Pasadena Jewish Temple and Center, born as Temple B’nai Israel in 1921, stood as more than a building; it was a bridge between history and the present. The congregation moved into a new Spanish-style building in 1941, which hosted USO-style dances for servicemen from the local military base during World War II.

Over the decades, it grew to 440 families — merging with nearby Shomrei Emunah and Shaarei Torah to become the singular Conservative synagogue of the Western San Gabriel Valley, adding buildings, a swimming pool, and a congregation that included NASA engineers, Caltech professors, and those who built their dreams among the stars. “I used to joke that growing up in Pasadena, our shul had doctors, lawyers and rocket scientists,” said Rabbi Alex Weisz, whose family has been members for generations.

For Weisz, PJTC was a second home. His grandparents joined in the 1960s. His parents were married at the same bimah where he and his siblings and cousins would have their b’nai mitzvah.

“I was a synagogue rat,” Weisz lovingly recalled of his youth, spending countless hours at PJTC — as president of the USY chapter and a teacher’s assistant in the religious school. “By the time I was a senior in high school,” he said, “I was there six days a week.” He credits those formative years with inspiring him to become a rabbi.

He is now the spiritual leader of Temple Beth Israel in nearby Highland Park, about 5 miles west of Pasadena. His parents are still members of PJTC; his dad, a past president, is now the vice president of the men’s club.

On Tuesday night, as the flames roared closer, Weisz helped his parents evacuate before rushing to All Saints Episcopal Church, which had become a refuge for those displaced. Hours later, word came that his own apartment was in the fire’s path, forcing him to seek safety at his sister’s home in Orange County. By Wednesday morning, the synagogue where his family had celebrated weddings, bar mitzvahs and a century of community was gone.

Yet, in the ashes of the building, Weisz found meaning in the teachings of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. “We are a tradition that sanctifies time, not space,” he said. “The synagogue is more than a location — it’s the connections, the love between people, whether they’ve been there for decades or are brand new.”

Cantor Berman Harris echoed the sentiment, invoking the biblical mishkan, the mobile tabernacle that journeyed with the Jewish people in the desert wilderness. “The Torah is a living dialogue,” she said. “There’s no more raw reminder of our resilience than carrying our traditions forward and finding a new way to rebuild. It’s the story of our people, and it’s tangible now in a way that it hasn’t been for generations.”