Why pro-Palestinian groups are being charged with fraud — and could pro-Israel groups be next?

A zealous lawyer got Jewish Voice for Peace to settle for $700,000, and pocketed $70,000 in the process

Demonstrators from Jewish Voice For Peace are taken into custody as they protest the war in Gaza at the Cannon House Building in July. The organization recently settled fraud allegations related to their eligibility for pandemic-era relief. Photo by Getty Images

In the fall of 2020, a New York employment lawyer, who moonlights as a legal crusader for Israel, went to apply for a pandemic government relief loan and noticed some restrictions had been added since a prior round of money was distributed to businesses earlier in the year.

The lawyer, David Abrams, saw that he was no longer eligible — but also sensed an opportunity: One of the new rules was that applicants had to certify they were neither a political advocacy organization nor a think tank.

He wondered: Might some of Israel’s antagonists have applied despite that prohibition? Abrams quickly found a handful that seemed to, and fired off legal complaints calling on the Department of Justice to investigate them for fraud.

It took a few years, but the gambit worked. Prosecutors announced Wednesday that Jewish Voice for Peace, one of the country’s most prominent anti-Zionist groups, had agreed to settle fraud charges for nearly $700,000. The fine is a significant blow to a group whose recent annual budgets were just under $3 million — and a boon to Abrams’ political agenda as well as his pocketbook: he’ll get $70,000 of the settlement under a DOJ rule that gives lawyers who file successful complaints a share of the spoils.

That’s on top of $1.7 million Abrams already pocketed from pandemic fraud-related cases involving companies with links to China as well as those involved with Israel. The Justice Department announced in September that Americans for Peace Now had agreed to pay $261,890 and in June that the Middle East Institute, a prominent think tank with ties to the Gulf States, settled for $718,558, both spawned by lawsuits Abrams filed.

In applying for the so-called “second draw” loans from the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program, those groups, like JVP, had checked a box saying that they were not “primarily engaged in political or lobbying activities,” or “organized for research” on public policy.

Abrams, who runs a for-profit legal agency called The Zionist Advocacy Center, has not been shy about the strategy that he’s used to pursue political opponents — in part, he says, because pro-Israel organizations like his own followed the rules.

“If I saw this was a big problem on my side, would I have opened this can of worms?” Abrams asked during a phone interview. “No.”

But government records show that at least half a dozen prominent pro-Israel advocacy groups, including StandWithUs and the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, also received second draw loans and do not appear to have been investigated by the DOJ.

Pro-Israel organizations escape scrutiny

The U.S. Attorney’s Office in Washington, D.C., which prosecuted the three successful cases brought by Abrams, said that it was legally obligated to “diligently investigate” any complaint it receives and “looks to ferret out fraud, waste, and abuse in all government programs no matter how it learns of those violations.”

The actions are filed under seal, and cases only made public when a conclusion is reached. So it is impossible to know whether some of the pro-Israel groups that got loans have also been the subject of fraud complaints that remain under investigation.

The Conference of Presidents — an umbrella organization whose 52 members include AIPAC, the Anti Defamation League and the Reform and Conservative movements — got a second draw loan of $100,740. The group was created to serve as the Jewish community’s voice to the White House, and its website describes it as a lobbying organization that “works publicly and behind the scenes” to “sustain broad-based support for Israel.” The group’s CEO, William Daroff, did not respond to inquiries for this article.

StandWithUs, which got a second draw loan of more than $1 million, is one of the most prominent national groups promoting Israel and defending its handling of the war in Gaza. It engages in many of the same activity as JVP: running petitions, offering “tools for activism” and posting about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict on social media. A recent report from the group touts it having run 80 successful campaigns defeating proposed Israel boycotts.

Asked about the restriction against political advocacy groups getting the loans, Roz Rothstein, the CEO, said: “Our organization is not primarily engaged in political or lobbying activities.”

Other organizations that received loans despite doing similar work as those targeted by Abrams — albeit on the opposite end of the political spectrum — include the American Jewish Congress, the Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting in America and the Jewish Institute for National Security of America, a think tank that argues “Israel is the most capable and critical U.S. security partner in the 21st century.” CAMERA denied any wrongdoing. AJCongress and JINSA did not respond to questions.

Even the Lawfare Project, which like Abrams pursues litigation against Israel’s perceived enemies, received a $90,852 second draw loan. A representative said the group’s “primary activities are strategic litigation and grassroots mobilization” and it received the funds “in line with legal and regulatory standards.”

Hadar Susskind, who led Americans for Peace Now at the time it applied for the loan, similarly said in an interview this week that his group did not see itself as primarily political. They settled, he said, because it was likely cheaper than a court battle, but believed the complaint was “very much ideologically motivated.”

(Americans for Peace Now subsequently merged with Ameinu, another liberal Zionist group, to create an organization called New Jewish Narrative.)

Which Abrams does not deny. He’s described his work as “lawfare for fun and profit,” but emphasized that he had carefully selected his targets: “Most nonprofits, and most advocacy organizations, do not fall within the SBA definition of ‘primarily engaged in political/lobbying activities.’”

(The Forward also participated in the pandemic loan program, receiving $596,203 in both the first and in second rounds, according to the federal database.)

A legal maze

Abrams and other agenda-driven attorneys, along with those motivated by the money they can win, are incentivized to file such complaints by the False Claims Act, an 1863 federal law overhauled 40 years ago to encourage whistleblowers with first-hand knowledge of fraud — say, a company employee — to alert the government about fraud.

“When it is genuine, it can be of real value and a reasonable basis to begin an investigation,” said Michael Galdo, the Department of Justice’s former director of COVID-19 fraud..

Individuals are allowed to file the complaints under seal, meaning they are initially kept secret from the party accused of committing fraud, and prosecutors can either bring charges, dismiss the case or allow the lawyer who filed it to pursue the lawsuit on their own.

The New York Times reported last year that as of April 2024, the Justice Department had opened more than 1,200 fraud cases related to pandemic loans, and by November had awarded more than $43 million to whistleblowers like Abrams, whose haul they tallied at $1.7 million. Another lawyer said he had filed more than 100 lawsuits, calling it “a gold rush.”

Abrams has been filing various types of lawsuits against organizations he dislikes for at least a decade, with mixed success.

The government declined to prosecute a 2015 case where he claimed that the Carter Center, founded by late President Jimmy Carter, had funneled money to terrorists by serving fruit and cookies at a meeting with Palestinian politicians. And in 2016, Abrams petitioned the Internal Revenue Service to revoke the tax-exempt status of Doctors Without Borders, similarly claiming that it was supporting terrorists. The IRS disagreed.

Abrams’ pandemic-loan campaign against pro-Palestinian activists has also not been foolproof. Federal prosecutors in Los Angeles and Denver declined to bring charges in response to his complaints against the anti-war group CODEPINK and a company that fundraises for Amnesty International, which has accused Israel of committing apartheid in the occupied West Bank and genocide through its war in Gaza.

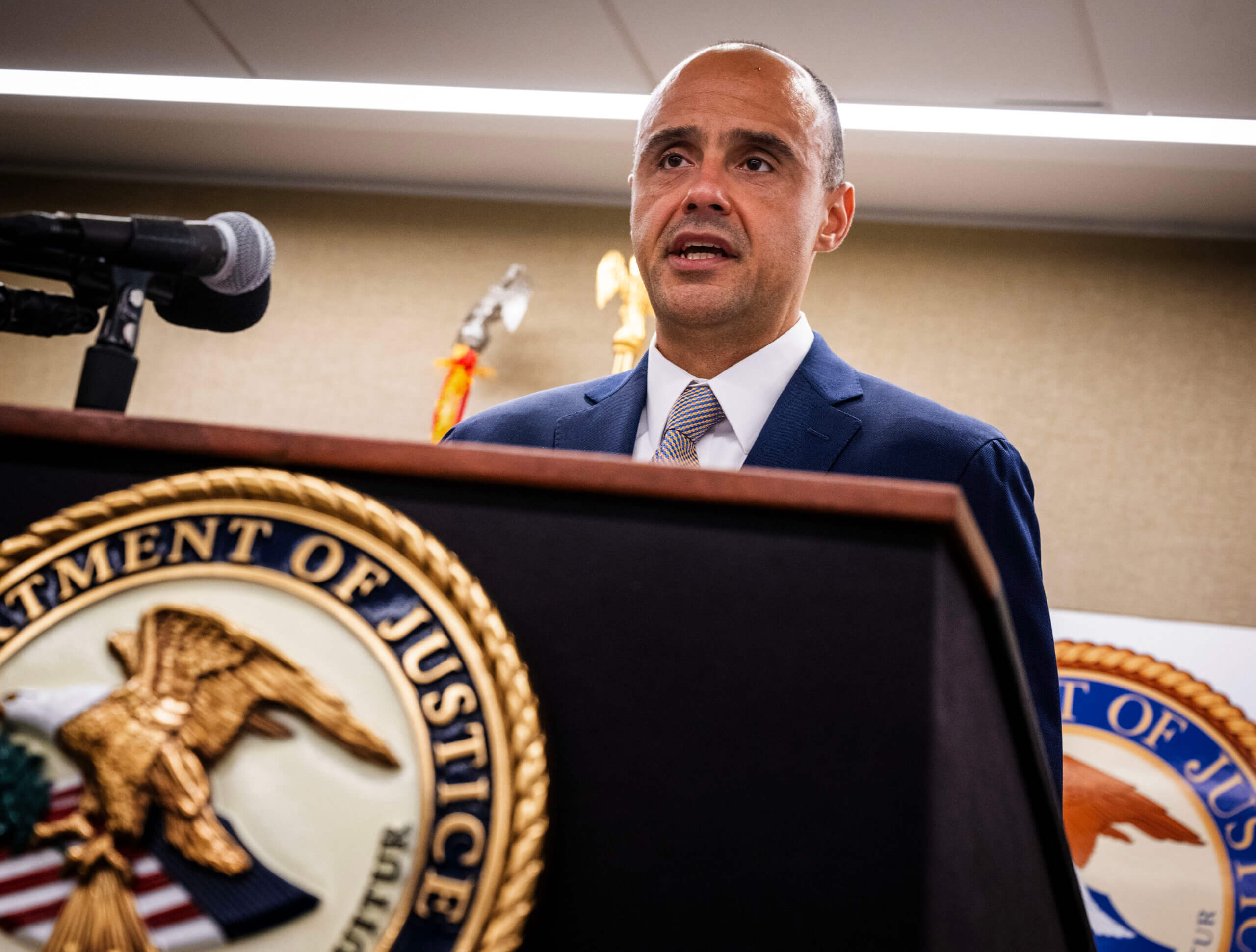

But he seems to have found a receptive audience in Matthew M. Graves, the U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia, whose office brought the charges against JVP, Americans for Peace Now and the Middle East Institute.

(Photo by Getty Images) Photo by Getty Images

“Obviously it would be a problem if the government was saying, ‘We’re going after this and not after that,’” Abrams acknowledged. “But I’m a private citizen, so that’s not really an issue.”

Mark Kleiman, an attorney who represents whistleblowers, said that prosecutors generally do not consider the politics of the groups targeted by fraud claims — or the lawyers filing them — even if it results in an imbalance in the cases that they charge.

“The lifetime career lawyers in the Justice Department take independence very seriously and take a lot of pride in actually calling balls and strikes,” said Kleiman, who has previously defended other organizations sued by Abrams.

Graves has also charged at least one right-wing think tank, the Center for Immigration Studies, with a similar type of fraud. But officials from that group sought to dismiss the charges in October, pointing out that they asked an official from the Small Business Administration whether they were eligible before applying for the loan and were told: “Go get the money.”

Joseph St. John, an attorney for the think tank, wrote in an October court filing that, after the group refused to settle the case, prosecutors “reached into the Godfather’s playbook” with aggressive demands that they turn over reams of internal documents. The case is pending

Jewish Voice for Peace said they faced a similarly invasive demand for documents and called the investigation “clearly politically motivated.”

Galdo, who ran the federal anti-fraud program until April, said that a campaign like the one being run by Abrams was worrisome. “If there are individuals with ulterior ideological motivations looking through publicly available PPP data, cherry picking examples that meet a discriminatory motivation,” he said, “it is an example of a troubling outcome.”