Why Nazis spent World War II in a luxury West Virginia resort

The strange, forgotten history of the Greenbrier hotel, where German diplomats and their families were treated to gourmet meals and spa treatments

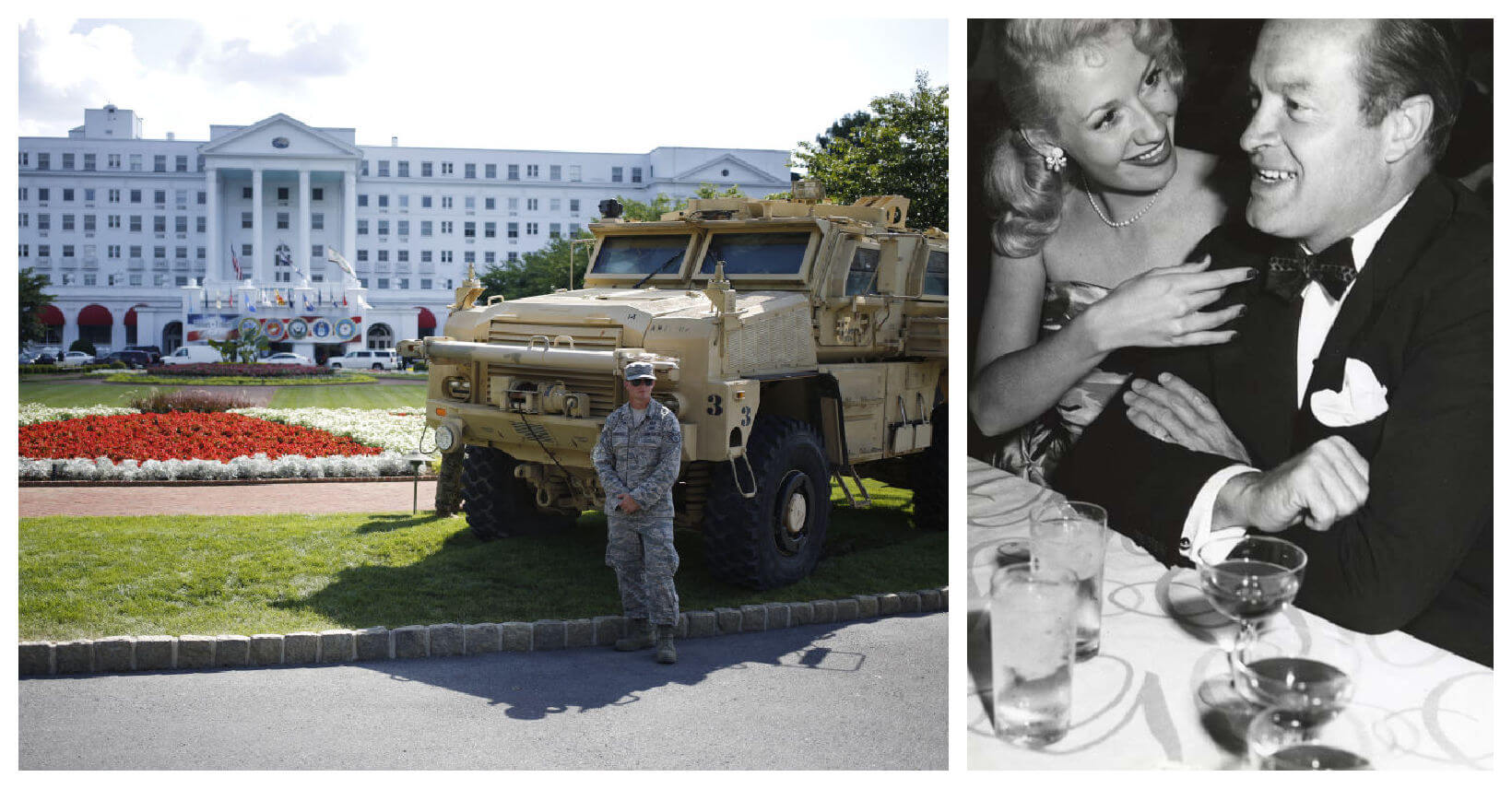

The Greenbrier resort in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. Photo by Ablokhin/iStock

Benyamin Cohen interviewed historians and traveled to White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, where he toured the Greenbrier for three hours — including the secret underground bunker built for members of Congress in case of a nuclear attack.

WHITE SULPHUR SPRINGS, WEST VIRGINIA — For a time, the men who helped run Hitler’s war machine lived like kings, tucked away in the snowy mountains of West Virginia. They woke to the scent of fresh linens and the sound of birdsong. They took leisurely breakfasts on fine china. At night, they lay their heads on down pillows in a grand hotel built for American aristocrats, a palace that had played host to presidents, celebrities and railroad barons.

This was war, but not for them.

The Greenbrier, a grand resort of the Appalachian South, had been turned into something absurd: a gilded cage for the very people America was about to declare war against. It was late 1941, and German diplomats — plucked from the embassy in Washington and consulates across America — were now the guests of their sworn enemy. They were not mistreated. They were not starved. They were not even made to wear a uniform. They were, instead, given rooms with a view.

At the Greenbrier, here on American soil, in a town famous for the healing powers of its sulphur springs, Hitler’s men slept in a five-star holding pen. And all the while, on the other side of the world, their country’s armies marched.

The U.S. government paid the bill — $10 a day per diplomat, about $200 in today’s money — covering meals, room service and all the comforts of captivity.

The reason? Diplomatic etiquette.

“The word is reciprocity,” said Harvey Solomon, author of Such Splendid Prisons, a book about the strange detainment of Axis diplomats at the Greenbrier and several other American resorts. The thinking went: If America treated Germany’s envoys well, maybe Berlin and Rome and Tokyo would do the same for U.S. diplomats trapped overseas.

A resort becomes a prison

I stepped into the lobby of the Greenbrier on a recent morning, and it felt like walking into Graceland if Graceland had hosted world leaders instead of rock stars. Plush carpets in vibrant greens and pinks. Oversized couches and chandeliers. A faint mustiness clinging to the walls, as if the past still lingered here. But this is no museum. It remains a bustling resort. The bellhops moved like actors in a period film, their uniforms crisp, their posture straight, their bouquets fresh.

I joined a tour group drifting from room to extravagant room, each drenched in a kind of unapologetic, high-society kitsch. The Greenbrier does not whisper subtlety. It demands admiration.

This is a hotel whose history is shaped by those who have visited — Bob Hope, Debbie Reynolds, John D. Rockefeller and a parade of presidents from Martin Van Buren to Donald Trump. Secretary of State Cordell Hull and his wife vacationed at the Greenbrier days before Germany invaded Poland and started World War II. In one ornate sitting room, an oil painting of Princess Grace, a one-time guest, watched over the grandeur with serene dignity.

The Bachelorette filmed an episode here. Hallmark made a Christmas movie here.

But I came chasing a story: For seven surreal months during World War II, Nazis lived here.

Diplomacy in paradise

The Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor propelled the U.S. into World War II. The country needed a place to detain Axis diplomats, and fast. “Government usually moves at a glacial pace, but this happened like a snap of the finger,” Solomon said, “when the Greenbrier immediately agreed to play host on short notice.”

Twelve days later, on December 19, 1941, Ambassador Hans Thomsen, Hitler’s top envoy in D.C., stepped off the train with his wife, Bebe. The train didn’t just stop near the resort. It stopped on the property. The Greenbrier had its own railroad station. Behind them, dozens of other Nazi officials followed — their briefcases still packed with the final telegrams from Berlin, their suits still pressed from their last embassy function.

Japan’s diplomats were sent to the Homestead, another luxury resort 40 miles across the border in Virginia. The Italians later arrived at the Greenbrier, but after incessant quarreling with the Germans were sent to the Grove Park Inn in Asheville, freeing up room for the Japanese to eventually move into the Greenbrier.

Many of the diplomats had been to the Greenbrier before. Some had spent summers lounging by the pool, walking its immaculate lawns, sampling its gourmet food, shopping in its boutiques. Now they returned under vastly different circumstances.

There was no forced labor. No internment camp. No rations. They ate what the guests would have eaten, drank what the guests would have had to drink.

The resort’s employees had only the diplomats and their families to serve. No other guests were allowed during the months of detainment. Reporters were also barred from entering the property, although that didn’t stop a few from trying. Three government agencies — the FBI, the State Department, and the Immigration and Naturalization Service — oversaw the operation.

By spring 1942, roughly 1,000 detainees packed the resort — diplomats, their wives, their children, even their dogs. The Thomsens brought their cocker spaniel, Peterkins. Children attended school in on-site cottages, while their parents played tennis, skated on frozen lakes and took swimming lessons from a former Olympian at the indoor pool. At least two women went into labor at Greenbrier during the detainment, with babies born at a nearby hospital.

Ordinarily, the Greenbrier hired an orchestra every year, but for the diplomats it chose only pianist Nathan Portnoff, whose playing on the ornate organ in the grand lobby entranced all, especially the children.

The irony? Portnoff was Jewish. His dad was a rabbi and his native tongue was Yiddish. His story partly inspired author Emily Matchar, whose historical novel, In the Shadow of the Greenbrier, imagines what it may have been like to be a Jewish worker at the hotel during those months.

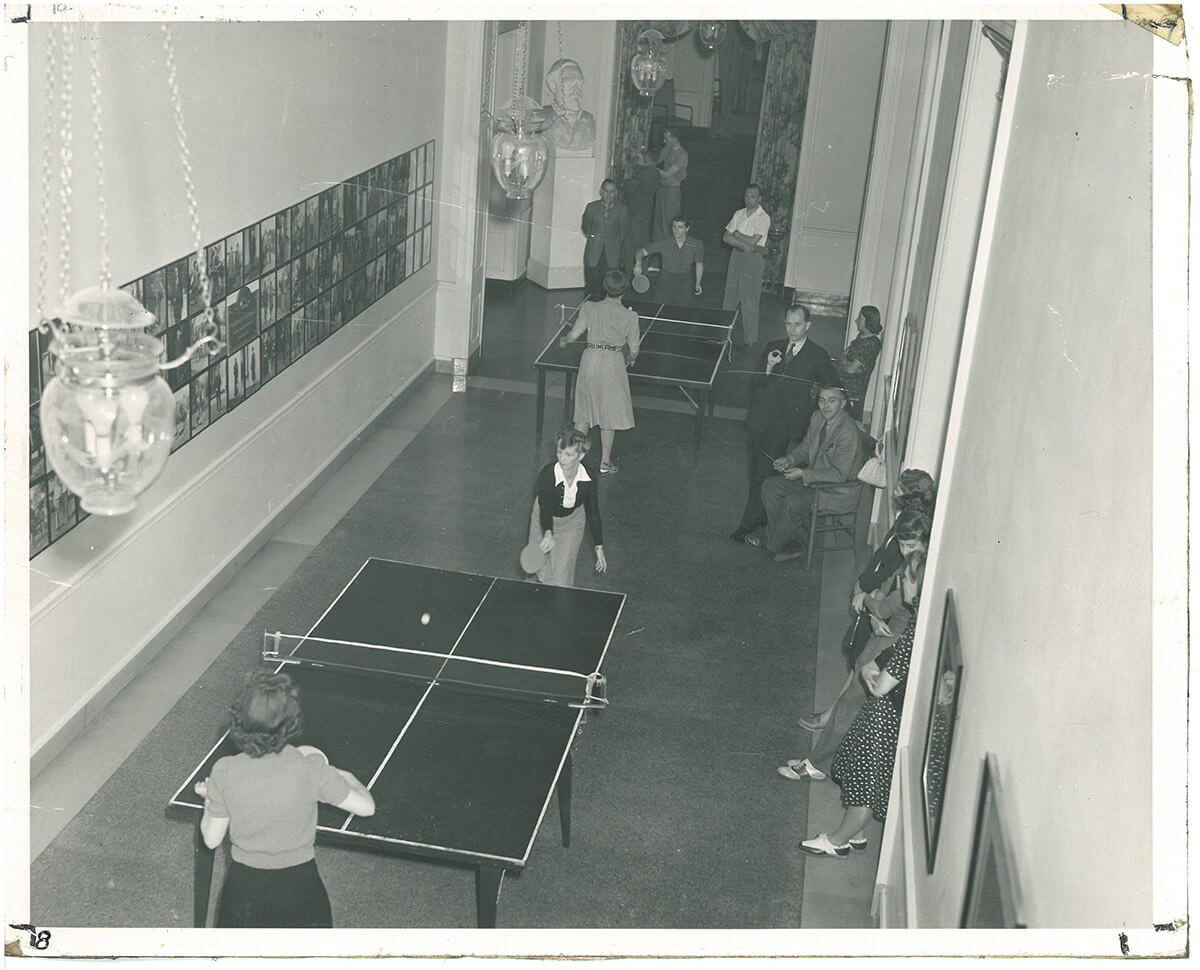

At night, the wives put on furs, and the men buttoned their tuxedos and waltzed into the Azalea Pink ballroom, where they dined beneath lights that had once twinkled for Southern debutantes.

On April 20, 1942, they threw a dinner party for Hitler’s 53rd birthday. “They had apple strudel and were screaming ‘Heil Hitler,’” Matchar said. It was a wild, boisterous affair, described by one waiter as a “hail of heils.” When the Greenbrier’s manager, Loren Johnston, was informed, he quietly spoke to Ambassador Thomsen. Fifteen minutes later the dining room was deserted, a testament to Nazism’s fierce devotion to law and order.

The diplomats continued receiving their salaries from Germany, delivered in cash by Swiss intermediaries. They splurged on alcohol and spa treatments. They spent money in the hotel’s many shops. The Greenbrier had a pharmacy, a men’s clothing store, a women’s boutique, antique shop, gift shop, florist, candy store, beauty shop, barber, post office, linen shop, even an ice cream parlor. “At first it was all high-end shopping,” Solomon said, “but when the merchants realized the Germans had money to burn, they quickly added staples like a general store — shoe leather, steamer trunks, foodstuffs, sundries and home goods.”

During my tour, a guide remarked that the wives of the German diplomats “arrived with two suitcases and left with 10.”

Spying on the guests

But the Greenbrier wasn’t just a high-class detention center. It was also an intelligence operation. The FBI quietly recruited hotel staff — bellboys, maids, waiters, valets — to eavesdrop on conversations to see if they could glean any kernel of information about Hitler’s plans. Some diplomats spoke too freely after a second scotch in the lounge, unaware that the man polishing glasses behind the bar was taking mental notes for J. Edgar Hoover. The masseuses were particularly useful, their clients loosened by hot stones and deep tissue massages.

Outside, the Greenbrier erected fencing along the resort’s perimeter and installed large lights that would stay on all night. (Some of the guests complained.) Agents who had been working at the U.S.-Mexico border were reassigned to the Greenbrier’s guard towers — a change of scenery, but a far easier gig.

“It was a cushy job,” Solomon said, “far from chasing illegal immigrants in far-flung flyspeck towns.”

“We were serving the country in the way a hotel, a resort, could do it,” said Bob Conte, the Greenbrier’s longtime historian. “It was easy to be patriotic in December, when business was slow.”

By May 1942, it was less convenient. Tourists wanted their resort back. By fall, the last diplomat was gone, shipped home as part of a diplomatic exchange. The Nazis left the way they came, by train, stepping off in New York, boarding a Swedish ship to Portugal, and eventually returning to Germany — not as prisoners of war, but as men of diplomacy, perhaps even men of influence. U.S. diplomats and their families, transported to Lisbon, took the same ship home in the opposite direction.

The Greenbrier’s second and third lives

After the Nazis left, the Greenbrier reopened to guests — but not for long. Within months, the U.S. government once again was asking for the Greenbrier’s help. The U.S. military soon took over the resort and converted it into a hospital for tens of thousands of wounded American soldiers returning from war. The same ballrooms that hosted Hitler’s envoys were transformed into triage rooms and recovery wards.

In 1962, the Greenbrier became the site of another mission. The U.S. government built a 112,000-square-foot nuclear fallout shelter underneath the resort, designed to house Congress in the event of an attack on Washington. Roughly 200 miles west of D.C., it was close but not too close.

Behind an 18-ton blast door and buried 60 feet underground, the Greenbrier constructed two large auditoriums to mimic the House and Senate chambers, so the work of the U.S. government could continue in a postapocalyptic world. I toured the dormitories and walked through the cafeteria where Congress was supposed to eat while the world burned outside.

The bunker remained a classified secret — and frozen in time — until 1992, when it was exposed by an intrepid reporter from The Washington Post. Some of the space is now rented out to an information technology company parking data servers there. But much of it remains unchanged; the Greenbrier offers tours of it for $52.

Greenbrier today

Sen. Jim Justice, Republican from West Virginia and one of the richest men in the state, has owned the Greenbrier since 2009.

Today, it has returned to what it always was: a retreat for the wealthy, a monument to privilege and selective memory. It remains a place of contradictions. You can come here for a spa weekend, or a golf tournament, or a falconry excursion. You can sit in the same dining room where Hitler’s men sat. You can sip a $19 mint julep cocktail in the same room where Nazis once toasted the Führer’s birthday.

You can stand on the veranda in the evening, listen to the cicadas and look out across the resort’s 11,000 acres. You can convince yourself that history is something that happened to other people, in other places, at another time.