Jewish Columbia student: ‘I don’t want Trump involved in my school’ but ‘nothing was changing’

A student who spent years trying to spotlight campus antisemitism is questioning what victory really looks like

An entrance to Columbia University in New York in March. Photo by Yuki Iwamura/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Eliana Goldin has been pushing Columbia University to take stronger action against mounting antisemitism for months. But last week, as the university agreed to ban face masks and take other steps demanded by President Donald Trump’s administration in an effort to preserve $400 million in federal funding, Goldin found herself grappling with a hollow sense of vindication.

“Trump was doing the thing we wanted him to do, which is crack down on antisemitism,” she said in a phone interview on Sunday. But, she pointed out, the White House is politicizing the issue, empowering those who disagree with Trump to also downplay the escalation of antisemitism on campus.

Goldin, 23, is in her final semester at the Jewish Theological Seminary and Columbia, where she’s majoring in political science. She co-chairs Aryeh, the pro-Israel group at the Columbia-Barnard Hillel, and hosts The Uproar, a podcast focused on campus antisemitism.

She has spent much of the school year feeling disappointed by the university’s reluctance to act. Now, the fixes are coming — but only, it seems, after Trump forced the school’s hand.

“Columbia should have done all this beforehand,” she said. “I don’t want Trump involved in my school. I don’t think anyone does. But the reality is that nothing was changing until Trump started waving the money over their heads.”

Linda McMahon, the education secretary, said on CNN Sunday that Columbia is “on the right track” to getting the money unfrozen, but stopped short of saying it was a done deal.

Goldin understands the uncomfortable political trade-offs involved. She said it’s “100% true” that Jewish students are being used as pawns. “And if Jews don’t treat themselves as a political force, ultimately, we’re going to be marginalized again.”

This tension mirrors a broader debate within the Jewish community over whether aligning with Trump will ultimately be more helpful than harmful. Goldin has come to believe that power, even if uncomfortable, is necessary. “It seems to me like we would let any other marginalized group use their power to make sure that they secured their civil rights,” she said. “But when it comes to us using our own power, all of a sudden everyone says it’s bad and we’re just like the oppressors.”

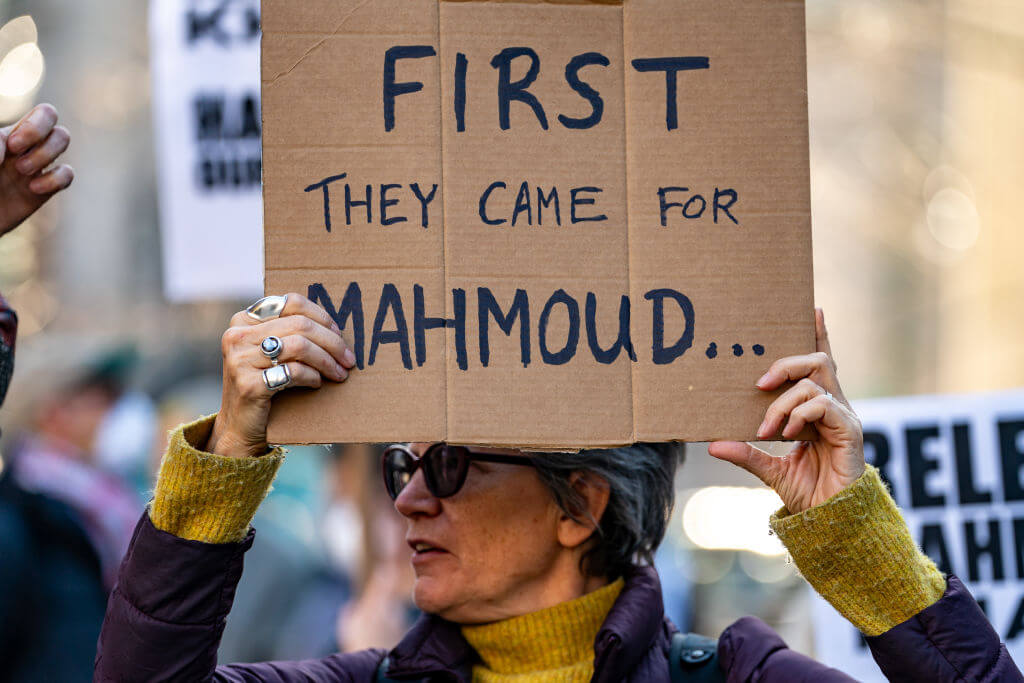

The case against Mahmoud Khalil

Goldin doesn’t join protests on Columbia’s campus. She stands on the sidelines, watching, flanked by others who do the same. One of the people watching with her sometimes was Mahmoud Khalil, a Palestinian student who graduated in December and is now facing possible deportation after his arrest earlier this month — a case that has become its own firestorm.

“You think everyone hates each other, but we’re literally standing next to each other watching over our communities, making sure everything’s OK,” Goldin said.

In a court brief dated Sunday, the Trump administration outlined its case for keeping Khalil in custody, alleging, among other things, that Khalil withheld that he worked for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees, commonly known as UNRWA, and arguing that should be grounds for deportation.

Khalil’s supporters say he’s being targeted for his political activity. Goldin says she despises the climate Khalil created for Jewish students, but still hopes “he gets a fair trial.”

“If he’s charged with an actual crime, then it’s justified,” she said, “and if he’s not, then this is the beginning of the end.”

What’s next

Goldin is uneasy about where all this is heading. “It’d be horrible to have police officers just running around, taking people off the streets, hoping it’s the right person that they have,” she said. “If someone broke a law and is on a visa, then it makes sense for them to be deported. The question is, if we want police running around, grabbing people and then realizing that they’ve got the wrong person. That’s not a state we want to live in.”

The lack of nuance in campus conversations exhausts her most. “The world is gray,” she said. “Protesters on Columbia’s campus have not engaged in that gray position, and they often force us to be black-and-white.”

She and others have tried to create opportunities for understanding. But the door keeps closing. “We were trying to have from the beginning a conversation and a dialogue, but they won’t even debate us, because then it gives legitimacy to Israel’s existence.”

The line between anti-Zionism and antisemitism, she believes, has grown dangerously blurry. “They’re not the same thing,” she said. “It’s when anti-Zionism becomes antisemitism which is the issue. That’s what we’re seeing in America, what we’re seeing on social media, and definitely what we’re seeing at Columbia.”

After graduation, she plans to head to Israel to study Torah for at least a year. She hopes it will be a quieter chapter — though she knows the noise will likely follow.

Asked about her long-term goals, Goldin’s answer was disarmingly simple. “Ideally,” she said, “I’d like to be happy at some point.”