What one Jewish reporter learned about forgiveness from two hate crimes in two sanctuaries

In his new book, journalist Kevin Sack examines how Charleston’s Mother Emanuel church and Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue became linked by violence — and grace

Worshippers listen to Rabbi Chuck Diamond, former Rabbi of the Tree of Life Congregation, as he conducts a Shabbat prayer vigil in front of the Tree of Life Synagogue on November 3, 2018 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, after a mass shooting there on Oct. 27 killed 11 people. Photo by Jeff Swensen/Getty Images

Two men of God stood side by side at the front of a church still marked by tragedy last week in Charleston, South Carolina.

The Rev. Eric S.C. Manning, pastor of Mother Emanuel A.M.E. Church, and Rabbi Jeffrey Myers of the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh embraced from the pulpit — clergy bound not by theology, but by the shared burden of leading communities through massacre and mourning.

Among those watching was Kevin Sack, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who had spent a decade chronicling the aftermath of the Charleston shooting. “It was amazingly moving,” he told me. “It really was a profound experience.”

That encounter bookended a relationship forged nearly seven years earlier — in the raw days following the deadliest antisemitic attack in U.S. history.

Sack, a longtime reporter for The New York Times, had traveled to Pittsburgh in November 2018 to report on the connections between that tragedy and the one he’d covered three years earlier: In June 2015, a white supremacist had opened fire inside Emanuel’s fellowship hall, killing nine faithful churchgoers during Bible study.

President Barack Obama’s soaring eulogy for the slain Rev. Clementa Pinckney — which concluded with him singing “Amazing Grace” from the pulpit — turned the Charleston massacre into a national moment of reckoning, and helped crystallize Sack’s sense that the church’s story was larger than a single act of violence.

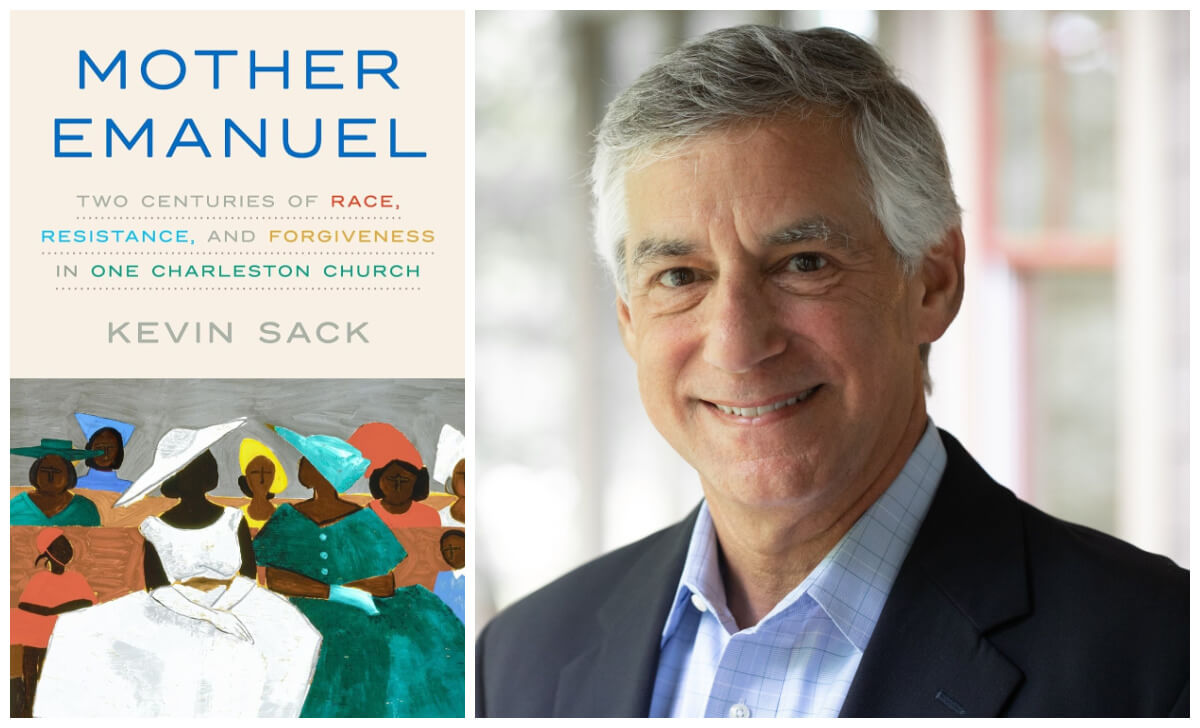

The shooting spurred Sack to chronicle the church’s 200-year history, a journey that culminated this month with the release of his debut book: Mother Emanuel: Two Centuries of Race, Resistance, and Forgiveness in One Charleston Church.

After the shooting, Mother Emanuel was not just a building or a community. “It was no longer just a church, it was now a shrine, one that beckoned with a spiritual power,” Sack writes. On Sundays, visitors would linger outside, pressing their hands and foreheads to the white stucco walls, “as if praying at the Wailing Wall.”

Sack — who grew up in Jacksonville, Florida, and now lives in Charleston — approaches his subject as an outsider, which he says was both a challenge and an advantage. “I was very sensitive to the fact that there were going to be a lot of fundamental things that I didn’t know or understand,” he said. “But coming at a subject like this as an outsider gives you a certain anthropological distance to see things in fresh ways.”

He interviewed hundreds of people for the book, many of them multiple times. For Sack, 65, a Reform Jew who once led his temple youth group, the experience was less about theology than empathy. The result is a work that offers a sweeping narrative of Black resilience in Charleston — and a deeply personal exploration of what Sack calls “the bewildering place of forgiveness within the context of unimaginable evil.”

It’s a tension he recognized after the Tree of Life synagogue shooting.

Faith and forgiveness

The parallels between the two attacks are haunting. Both took place in sacred spaces, both targeted minority communities, both were carried out by men fueled by online hate. And in both Charleston and Pittsburgh, grief gave way to something more complex: a conversation about forgiveness.

In Charleston, some family members of the victims forgave the shooter, Dylann Roof, just days after the massacre. It was an act Sack calls “otherworldly grace.”

In Pittsburgh, there was admiration but also ambivalence. Sack spent days outside the synagogue interviewing mourners. “Almost to a one,” he recalled, “they would go, ‘Oh my gosh, yes, I remember Charleston, what an incredible display.’ And then I’d say, ‘So do you feel the same way about forgiveness?’ And they would make it immediately clear that no, they did not.”

Sack said the Christian view of forgiveness is fundamentally different from that of Judaism, which delineates between sins against God and sins committed against man.

Teshuva, the Jewish concept of repentance, “is one that demands accountability in order for forgiveness to be granted,” he said. “And as it was explained to me by various rabbis, if you sin against God, for instance, by violating the Sabbath, you can pray to God and request His grace under those circumstances. But if you sin against man through a violent crime like this, the only way to to be granted forgiveness is to seek it from the harmed party. And in the case of a murder, that’s not possible because the victim is not there to grant that grace.”

Many of Pittsburgh’s Jews supported the death penalty for Robert Bowers, the Tree of Life shooter. Others did not. Beth Kissileff, whose husband survived the attack, wrote in the Forward that she opposed capital punishment despite her horror at the crime. So did some at Mother Emanuel, including Sharon Risher, who lost her mother and has been outspoken in opposing Roof’s sentence.

Today, both Roof and Bowers are in the same prison in Terre Haute, Indiana. Before leaving office, President Biden commuted 37 out of 40 federal death row sentences. The three remaining inmates are Bowers, Roof and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who was responsible for the Boston Marathon bombing along with his brother.

When sacred spaces become symbols

These theological and legal debates unfolded against another backdrop: the future of the congregations themselves. In his book, Sack writes that Mother Emanuel was once a mighty institution with thousands of members. But as of 2024, its membership had dwindled to 576. The church was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2018, which makes it difficult to abandon the site.

Mother Emanuel was not alone. Many other black churches in Charleston’s downtown area — also facing declining membership and buildings in disrepair — shut down or moved to other neighborhoods, chased out by high prices and gentrification. Several of the buildings were demolished and replaced by condos. Greater Macedonia church is now a cycling studio.

In Pittsburgh, where three small congregations had shared the Tree of Life building, similar questions persist. Millions of dollars have poured into rebuilding efforts — from philanthropists, corporations, nonprofits and government funding for a new synagogue, museum, and educational center. But some locals have asked: Why invest in dwindling synagogues? Should the money instead go to growing Jewish institutions?

“Obviously, they didn’t go back into the building,” Sack noted of Tree of Life. “They chose not to. And therefore they’re stuck with a whole different kind of expense.”

Sack doesn’t offer easy answers. What he offers instead is witness: to faith and doubt, to grief and grace, to the long arc of history bending through two sacred spaces scarred by hate.

In the days after the Tree of Life shooting, Rabbi Myers invited Pastor Manning to speak at the funeral for 97-year-old Rose Mallinger, the oldest of the victims. Manning read from Psalm 23 — “The Lord is my shepherd” — offering comfort to a congregation not his own but painfully familiar.

They had met just days earlier, in the lobby of a Pittsburgh hotel. They said nothing. They didn’t need to.

They simply embraced.