Alleged Adultery and the Wife’s Trial by Ordeal

If any man’s wife go aside… or if he be jealous of his wife, and she not be defiled; then shall the man bring his wife unto the priest….

A portion of our portion this week is about adultery. No, not adultery — alleged adultery.

Not only is Naso about alleged adultery, but more fundamentally, it is about what happens when an overwrought husband with an overheated imagination suspects his wife of (choose any or all of the following translations of Numbers 5:12) a) “going astray,” b) “behaving foolishly” or c) “turning aside to uncleanness [while she should have] remained underneath” her husband. There are no witnesses to this alleged crime (with witnesses, there would be death by stoning according to the Sinaitic code); no one is caught in flagrante delicto, and the wife doesn’t admit to a thing. The entire matter is hypothetical, conditional. To the husband, though, the wife has strayed from where she rightfully belongs — underneath him. She might have been under someone else. And he is having, as the text says, a “fit of jealousy.”

Oh, what to do?

Since there are no witnesses and therefore no legal recourse, the jealous husband does the next best thing and marches his wife off to the priest, also bringing along what is called a “jealousy offering.” Today we are shocked, shocked to discover that some of our rabbinate is sexually active beyond the boundaries of marriage, but our portion has no such trouble imagining the priest as eager to introduce himself into this domestic tangle.

At headquarters, so to speak, the priest puts water in a bowl, mixes into it some dirt from the tabernacle floor, loosens the woman’s hair (“uncovers” it, or “unbinds” it) and then warns the woman:

In the original Hebrew, he tells her that her womb will swell and her thigh — a euphemism for genitals — will wilt. The woman answers, “Amen, amen.” The priest writes these curses on parchment, dissolves some ink into the “bitter waters” and does his usual thing with the jealousy offering, waving and burning it. Finally he forces the woman to drink.

The narrative chronology is shaky. One suspects the scribe himself must have gotten a little overheated, just recording this stuff for posterity. But the gist is clear. The two men collude in the fantasy that this woman must be guilty of sexual infidelity and, with no proof whatsoever, they bring her to account, warning her that the “bitter waters” will uncover her guilt or innocence. At the climax of this ritual, the priest makes her swallow.

In the talmudic retelling of our portion in Mishna Sotah, the priest is even more overheated than in the Bible. Not only does he warn the woman that if she is guilty she will experience pain and sexual dysfunction from the bitter waters, but he actively engages in what we can only call role-play. He loosens her hair. He removes the clothes she has worn to the tabernacle and dresses her in penitential garments. He removes her jewelry. Lastly, he ties a rope above her breasts.

Once the activity gets going, the husband seems to have no role but to watch, whereas the priest is one busy boy, talking dirty, hands flying all over the place, bringing out his rope. And the woman’s response — “Amen, amen” — what are we to make of that? Is she frightened for her life? Sarcastic? Or does she actually give her assent? After all, the Hebrew Bible’s favorite romantic paradigm is the erotic triangle. Think of Abraham with both his old wife, Sarah, and his young concubine, Hagar. Think of Jacob, married to Leah but yearning for Rachel.

When the “ordeal” is over, readers all seem to agree that everything is just fine. Where the Bible text presumes guilt, albeit only in the mind of the husband and priest, later readers presume innocence. Rashi thinks the woman will have a good pregnancy. Modern commentators have her simply going home and resuming the marriage. Sweet.

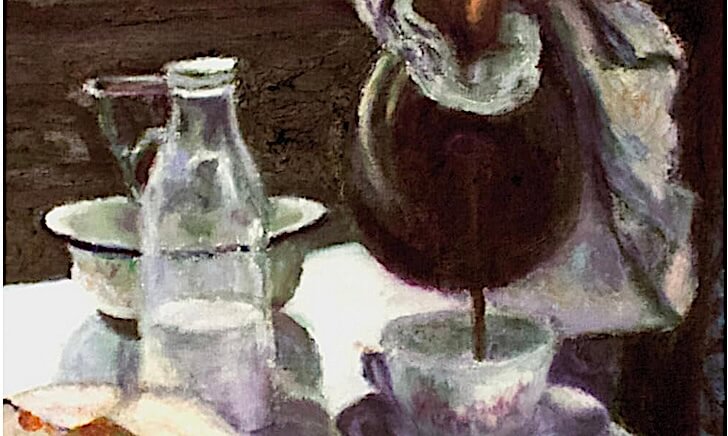

Another (modern) possibility: The woman takes leave of the two overwrought men and meets her best friend for the usual post-mortem. Over steaming lattes (decaf, skim), they dissect the event. “First they messed with my hair,” the woman says, lighting a cigarette. “You know — bed-head… sooo last year. Then there was that little B & D thing with ropes around my breasts. You’d think they’d at least try to be original. Helmut Lang’s been doing that for ages.” The woman inhales deeply, lets out a long plume of smoke. “Men are such jerks,” she says.

Evan Zimroth is professor of English at Queens College of the City University of New York. She is the author of four books, including the novel “Gangsters,” which won the National Jewish Book Award for fiction, and a memoir, “Collusion.”