DNA test kits spark a surge of online conversions to Judaism in the U.S.

Some people who felt a connection to Judaism discover hidden ancestry

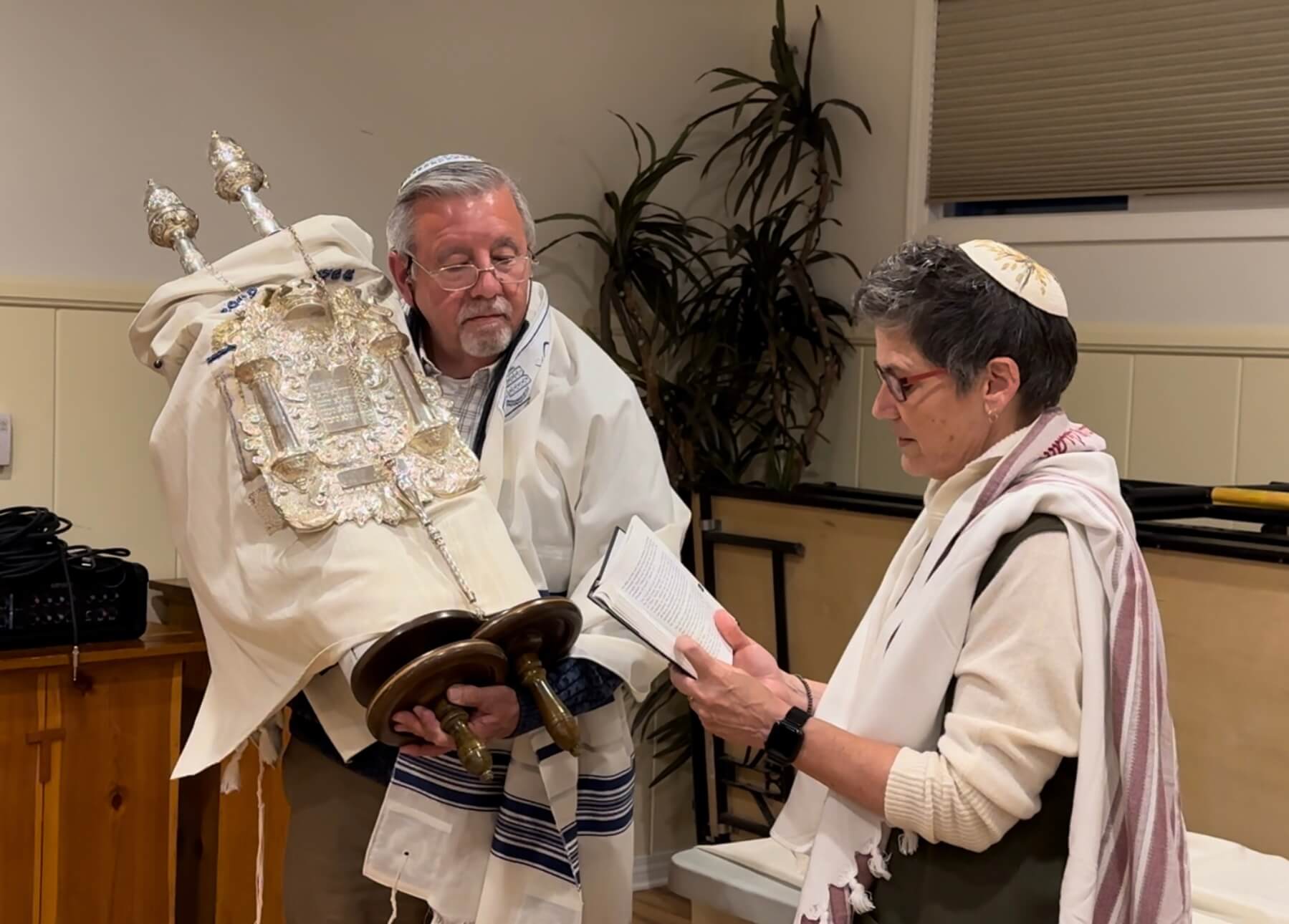

Joe Martin holds the Torah for the first time during his welcoming ceremony, where he was introduced to the congregation as having completed his conversion. Photo by Neona Lotz

Angie Claudio-Rodriguez was raised Catholic but felt a “deep connection” to Judaism she never understood.

Throughout her life, family members told her different things about her heritage, said Claudio-Rodriguez, 52. Some said, “We’re Irish,” others insisted, “We’re Native Americans,” and still others said, “We’re from Mexico.”

“It didn’t make sense to me,” she said.

Things came to a head on Oct. 7, 2023, when Hamas terrorists attacked Israel, killing about 1,200 people and taking more than 250 hostages to Gaza.

“Oct. 7 was a really tough time for me,” she said in an interview from her home in Lancaster, California.

That prompted her to do a DNA test, which she ordered on Dec. 29, 2023. A month later, she learned the truth.

“My mom is not Native American at all but from different parts of Mexico,” she said. “And my dad’s mom is Jewish. I had met her but she only told us that she was Catholic. … It was a shock to me. It just was really shocking. I felt like I was lied to my entire life.”

Armed with that knowledge, Claudio-Rodriguez took an 18-week introduction to Judaism class at the American Jewish University, based in Los Angeles, and then converted to Judaism. She has visited Israel twice and is now planning to make aliyah.

Claudio-Rodriguez is among a significant number of people who learned from a DNA test that they have some Jewish heritage and then decided to convert to Judaism.

Discovering hidden Jewish heritage

“There is a dramatic global interest in discovering if people have Jewish roots,” said AJU president Jay Sanderson.

In fact, interest in Judaism has increased to such an extent that Sanderson said hundreds of students from across the country are currently enrolled in AJU’s introduction to Judaism class.

Unlike synagogues, which generally offer only in-person introductory classes – available exclusively to their members – AJU is offering its classes to anyone.

“I think the biggest thing is that you have this program online and people can access it,” said Rabbi Tarlan Rabizadeh, vice president and director of the university’s Mass Center. “A lot of people find out that they have Jewish heritage and they want to learn more.”

As a result, its current introductory course is being taken by many non-Jews. The university said it did not know how many non-Jews are enrolled, but noted that there are a total of 892 students in the current class. They are from every state except Wyoming and many countries, including Portugal, France, Lithuania, Malawi, Turkey and Norway.

In the last two years there has been increased interest in genetic testing in Spanish speaking countries in Latin America and Mexico, Sanderson said, and as a result, the university is offering its introduction to Judaism classes in Spanish as well. In addition, there are a large number of Iranians in Los Angeles and many are “also curious to know whether they are Jewish or not.”

“Just a couple of months ago a Spanish speaking community went through our program and they had stories about how their ancestors had come from Argentina, that their ancestors were forced converts and they wanted to go back to their roots,” Rabizadeh said.

“What we’re seeing here is people who are not Jewish, who are taking the DNA test, discovering that they have even 2% Jewish heritage, and deciding to convert to Judaism,” she added.

“This is a new phenomenon,” Sanderson said.

“Many of the non-Jews in the class convert,” he said, while many others “are interested but not necessarily ready to do a DNA test.”

DNA tests confirm a Jewish ‘feeling’

Across the country at New York City’s Central Synagogue, one of the country’s largest Reform communities, Rabbi Lisa Rubin said the Center for Exploring Judaism is not seeing the surge from DNA testing that California’s AJU is experiencing. Rubin said there was an increase in conversions right after Oct. 7, but no increase related to DNA testing.

Though the Jewish population is estimated at 16.5 million, there may be as many as 60 million people around the world with Jewish ancestry, according to AJU’s website.

Claudio-Rodriguez, a public school teacher, said none of the members of her family were aware of their family’s Jewish ancestry, and none plan to convert to Judaism.

She keeps kosher, attends Sabbath services weekly, wears a Star of David, is studying Kabbalah, or Jewish mysticism, and has eight children and a four-year-old grandson, she said. She does not know if his parents will raise her grandson as a Jew, but she’d “absolutely love it” if he has a bar mitzvah, she said.

Like Claudio-Rodriguez, Joseph Martin, 66, took a DNA test. Martin, who took the test in early 2021, said he “had always felt Jewish.”

But he was raised in an “Hispanic family, and we were very, very Catholic. My mother was a devout Catholic, going to church every Sunday. I went to Catholic schools through the eighth grade. And you know, gosh, Jewish was kind of a naughty word in the household when you’re raised as a Catholic because, after all, you know the Jews killed Jesus. Those were the kind of things that you hear, you know, as a kid growing up. … I wish my mother was alive today so that she could take her DNA test and find out that she was Jewish all this time.”

Through his genealogy research Martin learned that his family is from a large Sephardic family in Guadalajara, Mexico, he said, and that “they have always been Portuguese Jews.”

“You have to recall that during the Inquisition the only way to stay in Spain and Portugal was to convert to Catholicism or leave,” he said in an interview from Lompoc, California, where he lives with his wife Neona Lotz.

“If you were discovered practicing Judaism, you were burned at the stake. In order to convert, you had to have a sponsor, and the sponsor could have been your employer. … And the employer’s last name was Santiago and you took on his name in order to convert to Catholicism. So Santillan is my family name. That’s the Jewish side of my family,” he said. “Who really knows what our Hebrew last name might have been? I’ve never been able to find that through all my research.”

Although he had dated Jewish women, Martin married someone who was Catholic. Now divorced, he went online to meet someone, he said. “The first thing I noticed in one of the profiles was that she was Jewish. I said I’ve got to meet this woman. We’ve been together for 11 years.”

When he learned four years ago that DNA results revealed he is 2% Jewish, he told his wife that he planned to convert to Judaism. She replied, “The Jewish soul always returns.”

Correction: This article has been updated to fix an error in Joe Martin’s family name. It was Santillan, not Santiana.