Viewing Pop Culture (And Life) Through Baby-Colored Glasses

I knew becoming a mother would change my life. I was ready for the sleeplessness, the proliferation of tacky stuffed animals, the Old Faithful-esque lactating unpleasantness. What I was not prepared for was the way my entire outlook, even on non-baby-related things, changed. Suddenly, my cultural filter was fogged with babyness. I viewed the world through baby-colored glasses.

Example: The first movie I attended after Josie’s birth was “Artificial Intelligence: AI.” It was certainly among the worst films I have ever seen, far surpassing the epic badness of “Porky’s 2,” “Battlefield Earth,” “The Bad News Bears Go to Japan,” late-night cable porn or any driver’s-ed car-crash film. My husband, who spent those three hours emitting low, agonized moans, growled like an animal when the lights came up. “Steven Spielberg owes me $20. Stanley Kubrick is lucky he’s dead.”

Jonathan loathed the queasiness-inducing mix of Kubrick’s sour worldview with Spielberg’s syrupy, perky one, as well as the talking teddy reminiscent of Cuddles the fabric softener bear and the Spielberg-patented triple-fooled-ya faux-ending. Intellectually, I hated it for all the reasons Jonathan did. But emotionally, I was devastated. The mother who threw out her adoptive robot son when her biological son came out of his coma, who made the once-loved adoptive son sit alone in a corner while the family slept, who finally drove the child into the woods and released him there, to fate — well, I wanted to kill her.

Her character was supposed to be nuanced, but I viscerally hated her, and I hated the movie for making me sit through little Haley Joel Osment’s suffering. And the plot was about his attempt to get back to his (evil, to me) mother, so the entire film was lost to me. Before I’d had Josie, I simply would have frothed at the mouth about an over-praised filmmaker’s tendency to be self-indulgent and sentimental, to play to his own worst instincts, to destroy the legacy of a far more talented and honest visionary. But now I’d lost all objectivity. A kid suffered; I sobbed. Let’s say I lacked Kubrickian dispassion. The only saving grace was that my parents were baby-sitting and I didn’t pay $60 instead of $20 for the privilege of weeping for three hours while telling myself that having this much emotional investment in a crappy piece of fiction was really ridiculous.

My emotional response to children suffering didn’t recede after the wash of new-mom hormones did. Months later, when I watched one of my favorite shows, “Six Feet Under,” all I could focus on was the baby playing Maya. What kind of parents would let their infant be in a scene in which adults were screaming at one another? As the character of Nate, Maya’s father, unraveled, I sniveled with fear for Maya. The baby actress and the character were all mushed together in my mind. Poor Maya, a baby who’d had loving parents and an attachment-parenting, co-sleeping childhood suddenly had a missing and probably dead mother and was dumped into a crib every night. She spent hours in her crib, ignored. Her father was going on drunken binges. I felt sick for the little baby actress, witnessing all these adults screaming at each other.

I got so worked up, I could barely look at the screen. My friend Daryl finally sat me down and showed me how, thanks to clever editing, the baby actress was never subjected to yelling. She wasn’t even in the scenes in which there was fighting. The director would cut to a reaction shot of the baby in her high chair, or of Nate’s mother, Ruth, holding her, but there was never a shot that contained both the baby and an out-of-control adult.

And then there are the newspapers, which are entirely different documents to me now. Every terrorist bombing, every plane crash, every picture of a dirty, starving toddler makes me think, Oh God, what if that were my baby?

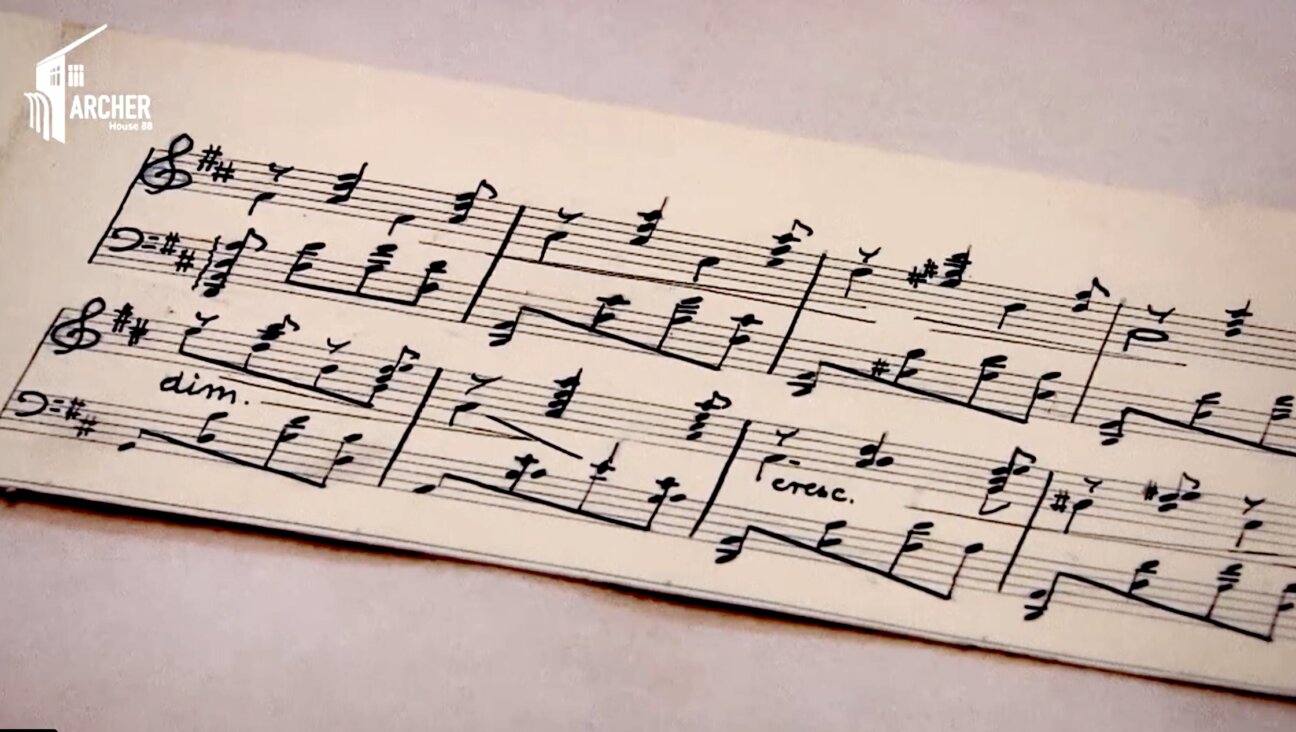

Becoming a mom changed the filter through which I viewed the world. When I saw Robert Wilson’s production of “Woyzeck” at the Brooklyn Academy of Music earlier this year, I looked past the stylized, stagy tableaux, dissonant music and chilly Brechtian Expressionism and saw an orphaned child. I felt no distance. A few months later, I raged at the publication of Maria Flook’s “Invisible Eden.” The book is an account of the death of writer Christa Worthington, who was murdered by an unknown assailant. Her toddler was left alone with the body for more than 24 hours. When Flook’s book came out a few months ago, only a year after Worthington’s death, I felt sick. It discusses the dead woman’s romantic life and bad choices, and uses Capote-esque New Journalism techniques to describe behavior and thought processes the writer couldn’t possibly know. And one day, her baby daughter will be a grown-up and will read it.

On the other hand, being a mom has also deepened my understanding of art. When I went to David Lindsay-Abaire’s wonderful comedy “Kimberly Akimbo” at the Manhattan Theatre Club back in February, I understood it in a way I couldn’t before I had a child. The play is about a teenage girl with a fantasy version of progeria, a rare and fatal genetic disease. Kimberly has to contend with a crazy, white-trash family that doesn’t understand her — a drunk and unreliable father, a criminal aunt, a self-absorbed hypochondriac mom. Yet she loves them, and she loves being a kid in the world. Ultimately, she falls in love and embraces risk, even as it makes the world a little bit scarier. The play is hilarious (I wish it a long life in repertory companies around the country), but it is also completely infused with an awareness of mortality. Loving people means accepting that you will lose them. Now that I’m a parent, I truly understand that. We can shield ourselves from art and pop culture that hurt, but we can’t shield ourselves from that fact. And maybe it’s better not to. Love is all the sweeter because, like infancy, it’s something we can’t hold onto forever.

Write to Marjorie at [email protected].