Gaming platform Roblox has ‘zero tolerance’ for antisemitism. Holocaust reenactments keep reappearing anyway.

Roblox users persistently share antisemitic content through coded language

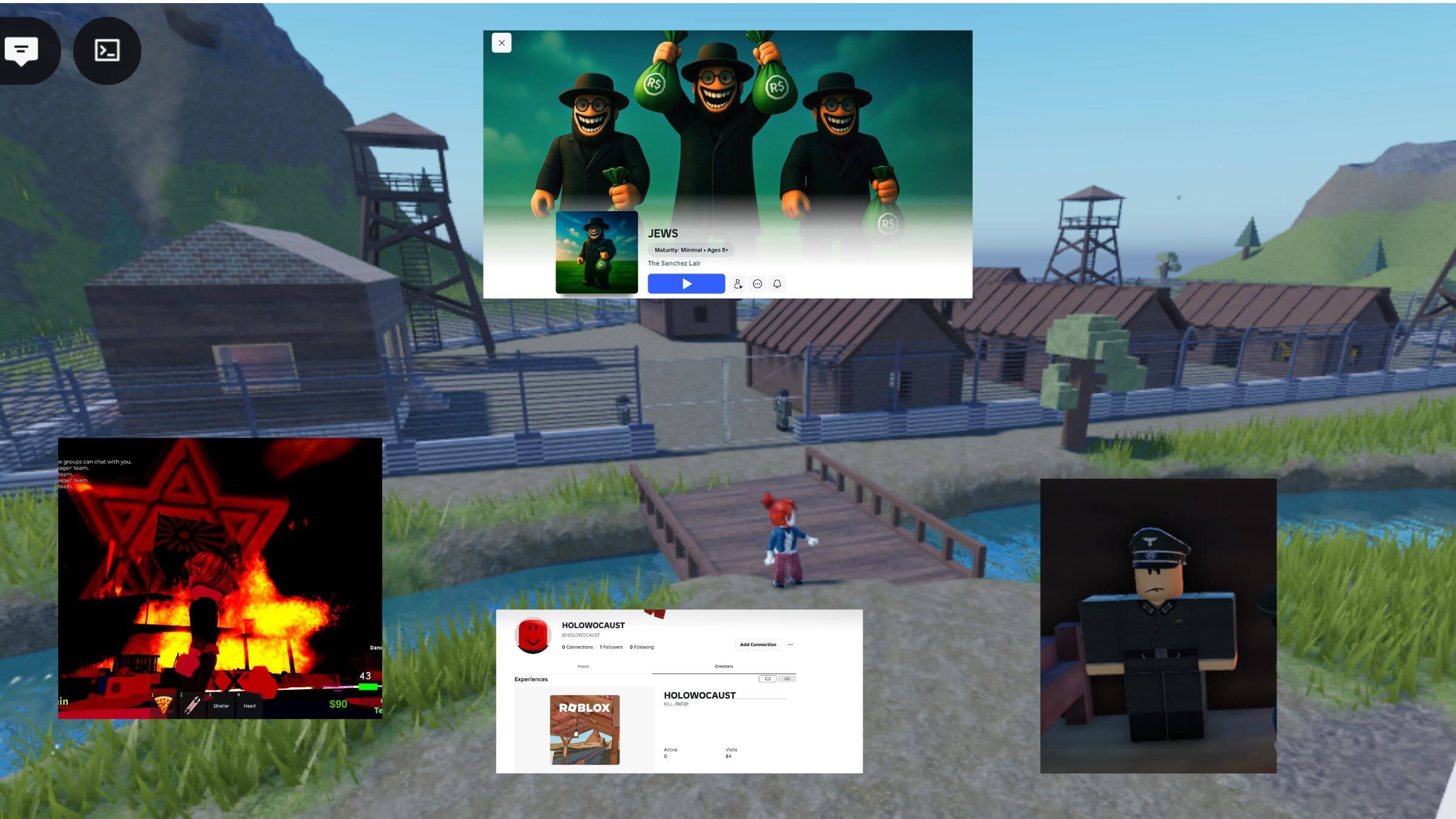

Screenshots from the gaming platform Roblox. Graphic by Hannah Feuer via Canva

As the game “German Camp” begins, you arrive at a virtual building with a large German flag on display. There, on the gaming platform Roblox, your avatar can put on a helmet labelled “Stahlhelm,” the steel headgear worn by Nazi soldiers during World War II. Next door, soldiers stand watch over fenced-in barracks where characters labeled “noobs” — a derogatory term for inexperienced gamers — line up to be killed.

“This is the best place in the world,” a user named Bravado writes in the chat before shooting your character — as happened to this reporter.

Roblox, where users can create their own virtual worlds — and explore millions more made by other players — says it has a zero tolerance policy against antisemitism. But Holocaust scenes and imagery have continued to appear on the platform for years.

In 2022, Roblox removed a simulation of Nazi gas chambers, which users could operate by pressing “execute.” The Global Network on Extremism & Technology found a game titled “1941 – Konzentrationslager Auschwitz” on the platform in October 2025.

“Hate or harassment targeting Jewish people or any religious community is strictly prohibited on our platform,” Roblox spokesperson Eric Porterfield wrote in a statement, adding that “we take swift enforcement action against users we find violating our rules.”

Roblox removed “German Camp” shortly after the Forward’s inquiry about the game and confirmed it violated the platform’s policies. The game, advertised for ages 13 and older, had been played 174 times and was available for about two years.

‘No system is perfect’

Roblox prohibits content that “recreates specific real-world sensitive events” and “supports, glorifies, or promotes the perpetrators or outcome of such events,” including the Holocaust.

But “no system is perfect,” Porterfield wrote in a statement, adding that Roblox relies on a combination of AI detection, human reviewers, and community reporting to identify and remove antisemitic content.

In the case of the “German Camp” game, a member of Roblox’s public policy team told the Forward that the game would have been flagged immediately had it used the term “concentration camp.” Without such keywords, however, content can be more difficult to detect.

Roblox’s AI filters scan for terms like “Nazi,” automatically removing some content and identifying ambiguous cases for human review. The company works with thousands of contractors to evaluate flagged material, and players can also report misconduct directly. Roblox said it then evaluates player histories to help determine the severity of the offense, and disciplines players accordingly.

But Constantin Winkler, a researcher at the Global Network on Extremism & Technology who has studied extremist content on Roblox, said users evade these guardrails by intentionally misspelling words or communicating in code.

For instance, the Global Network on Extremism & Technology identified usernames such as “lolocaust,” “Atolf Zitler,” and the use of “88” — code for “Heil Hitler,” with “H” being the eighth letter of the alphabet.

Roblox said it found and removed 61 accounts, one game, and two groups that violated their policies after the Global Network on Extremism & Technology’s report in October about extremist content on Roblox.

But the Forward this month identified users named “konzentrationKamp,” “konzentrationausch,” “konzentrations_lager,” and “holowocaust,” and games titled “The Camp 1942” and “271k or 6 million,” referencing the conspiratorial claim that only 271,000 Jews were killed in the Holocaust. Other problematic content was more explicit: a game titled “JEWS,” featuring images of men in black hats clutching money bags, or “LIFE IN ISRAHELL,” featuring Stars of David set ablaze.

“They try to take some things down, but you can always find it again,” Winkler said.

Roblox works with organizations including the Anti-Defamation League, Tech Against Terrorism, and the Simon Wiesenthal Center to constantly audit and strengthen its moderation policies, according to its policy on safety and civility.

According to Winkler, Roblox users also frequently encounter players building or drawing swastikas during live gameplay. Because these actions happen in real time, he said, they are far more difficult to moderate than problematic usernames or pre-built worlds.

That’s a familiar challenge for Tristan Brown, a 19-year-old Jewish college student who was playing a Roblox spray-paint game when, suddenly, his player was surrounded by graffitied swastikas. He and his friends quickly logged off.

“It makes me want to stop playing on the platform, because if I’m gonna be playing, why can’t I be respected?” Brown told the Forward. “I wish there was more of a crackdown on things like that.”

A broader challenge

Video games reenacting concentration camps are not new: In 1991, a video game called “KZ Manager” circulated in Austria and Germany, where the player runs the Treblinka death camp.

Hate groups have also long used video games as a medium of choice. In 2002, the white supremacist group National Alliance created a video game titled “Ethnic Cleansing,” a first-person shooter game where players participate in a race war, killing stereotypically-depicted Jews, African Americans and Latinos.

But these games are generally created by extremists, for extremists, Winkler said. Roblox, meanwhile, is a mainstream gaming platform with 82.9 million daily active users last year. About 40% of its users are under the age of 13.

Roblox is far from the only popular gaming platform that’s struggled to crack down on hateful content: Minecraft, Steam, and Discord have all come under fire for neo-Nazi content — as has virtually every video game or streaming platform with a substantial following. In the digital era, it’s practically a given that platforms built around user-generated content will attract hate. Video games, many of which combine anonymity, creative freedom, simulated violence, and the ability to interact with other players, are especially fertile ground for extremism, Winkler said.

In response to the spread of extremist content, educational Holocaust-themed video games have emerged, including a virtual Holocaust museum hosted on Fortnite. But these efforts have also drawn harassment: The project’s release was delayed after white nationalist influencer Nick Fuentes urged neo-Nazis to target it.

A 2022 survey from the Anti-Defamation League found that 34% of Jewish gamers said they experienced identity-based harassment while playing. Players most often encountered white-supremacist ideologies in the games Call of Duty, Grand Theft Auto, Valorant, PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds, and Fortnite, the ADL found. Then last year, the ADL tried logging onto various video games with the username “Proud2BJewish” — and 38% of their gameplay sessions resulted in some form of harassment.

Meanwhile, overmoderation — particularly when it relies on unreliable artificial intelligence — can backfire, sweeping up innocent users and undermining trust in moderation systems. At the same time that Roblox has faced scrutiny for failing to curb antisemitism, its forums are rife with complaints that the platform’s moderation system is plagued by false positives.

Efforts to police content in video games have also long raised concerns about censorship and government overreach. After the 1999 Columbine High School massacre, a moral panic took hold around video games when the perpetrators, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, were revealed to be avid players of violent video games. Subsequent research has largely failed to establish a causal link between violent video games and real-world violence.

For Winkler, the central danger is not that a player will encounter a depiction of a concentration camp and immediately become radicalized. Instead, he said, the concern is more insidious.

“In our research, we don’t even care about, Is it ironic? Is it humor? Because extremist content is extremist content, and it’s available,” Winkler said. “It’s really dangerous because it’s part of a normalization process.”