Rabbi and Former Nun Settle Down in Miami

To the two protagonists, it is the heartwarming story of how a small-town Conservative rabbi and a flamenco dancer-turned-Russian Orthodox nun fell in love and wound up living together in a condo in Miami. The rabbi’s heartbroken wife and his irate former congregants, however, see a sordid tale of betrayal and abandonment.

Whichever description one chooses, the latest twist is the same: Rabbi Ephraim Rubinger, 62, recently resigned his membership in the Conservative movement’s Rabbinical Assembly as the organization launched an ethics investigation into his conduct. Rubinger is casting his resignation as an act of defiance and principle, saying that he quit the R.A. rather than submit himself to the judgment of a “kangaroo court.”

The resignation could prove to be the final chapter in a scandal that rocked the Jewish community in the sleepy town of Columbia, S.C. — population 116,000 — where Rubinger served as the religious leader of Beth Shalom Synagogue from August 2005 until being forced out three months ago.

Last summer, Rubinger moved to Columbia with his wife, Diana, and his 13-year-old son from a previous marriage. Just an hour’s drive to the south lived a nun by the name of Leslie Villaverde who had spent the past six years at the Saints Mary and Martha Orthodox Monastery in Wagner, S.C.

At the time, Villaverde was in the throes of what she now describes as a “crisis of faith,” and she had furtively begun to explore Judaism. She signed up to receive Rubinger’s “Torah Talks” via e-mail. Soon the two developed an e-mail rapport, and even though they’d never met, “it was obvious,” Rubinger said, that “we were developing very strong feelings for one another.”

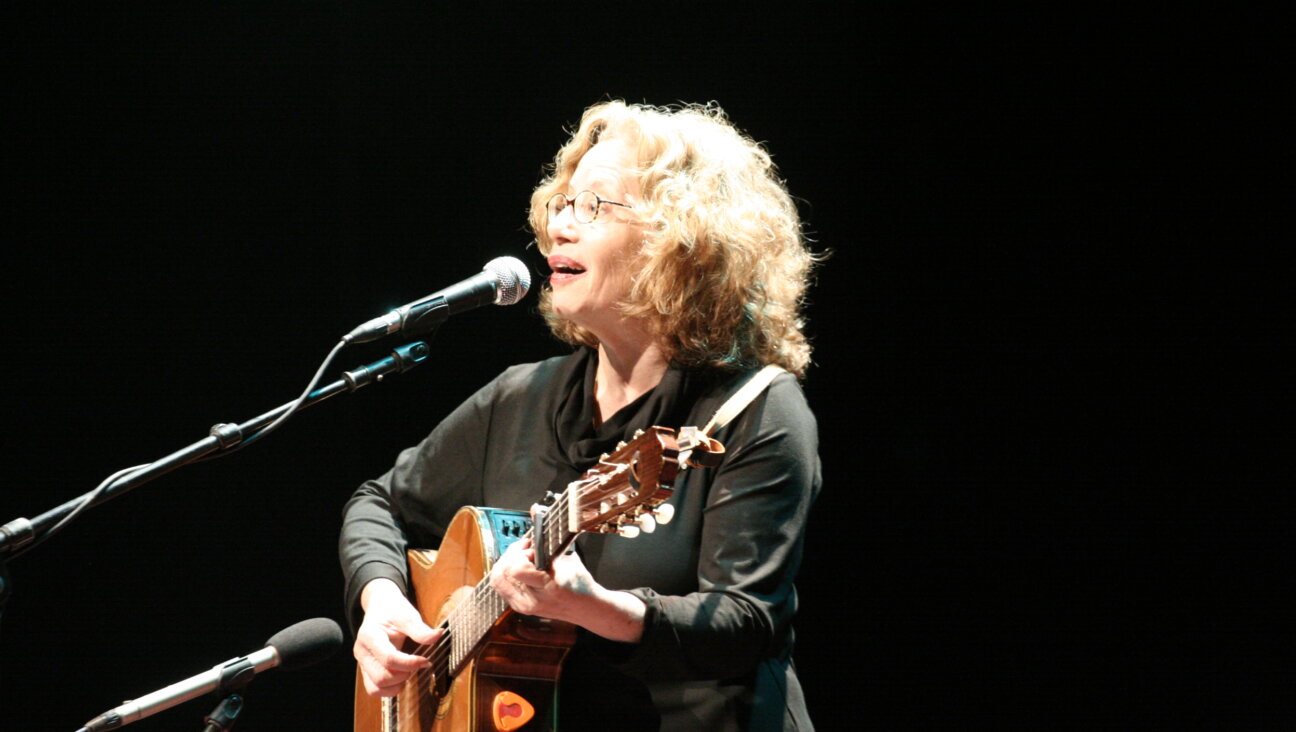

Ultimately, Villaverde, now 52, decided to abandon the Russian Orthodox Church for a Jewish life. “I was completely ostracized by the Orthodox Christian community,” she said.

Rubinger sent one of his congregants to pick her up from the abbey, collected donations on her behalf and referred her to Jewish family services for financial assistance. The way the rabbi and the community saw it, Villaverde was returning to her faith: She was born to a woman who had converted to Judaism, making the ex-nun a Jew under their interpretation of rabbinic law.

Villaverde, who had given away her Florida condo and all her money to the abbey when she took her vow of poverty, was offered housing by a Beth Shalom family. Rubinger convened and served on a rabbinic tribunal that recognized her return to the Jewish fold.

After extending a warm welcome, congregants quickly noticed that their rabbi and the former nun appeared to be enamored of each other. “Not that we did anything, but I guess people were able to discern that we were very much in love,” Rubinger said.

Rubinger said that his wife confronted him in reaction to rumors that began circulating a few days after Villaverde’s arrival. When the rabbi acknowledged his feelings for his new love, his wife asked him to leave.

Next, Rubinger said, the community was in “hysteria.”

Both Rubinger and Villaverde insist that their relationship was strictly platonic.

“As it turned out, Ephraim and I were just friends, but things blew up and it turned out that we did, indeed, have love for one another, but certainly nothing had happened,” Villaverde said. “But [the congregants] indeed threw us together by their hatred of me.”

“Within a few days I was labeled a whore, a slut that had left the monastery to have an affair with the rabbi,” she said. “I saw there was no way to take money from Jewish family services because it would be thrown back in my face.”

In response to the uproar, Rubinger said, he returned all the money that he had raised on behalf of Villaverde.

The rabbi and the former nun say they were both run out of town: Rubinger was pushed out of the congregation, and Villaverde fled to a friend’s home in Springfield, S.C., before making her way back to South Florida, where she had lived and worked as a legal secretary before joining the abbey. She got her old job back, and Rubinger joined her soon after. The two of them are now living together, and Villaverde, who recently took the Hebrew name Ruchama, says the couple plans to wed as soon as the rabbi finalizes his divorce.

Rubinger contends that before he met Villaverde, he and his wife were experiencing marital problems because of their differing levels of religious observance. According to the rabbi, who maintains the laws of kashrut, his wife sometimes ate lobster and shrimp. Diana Rubinger, a 58-year-old middle school science teacher, didn’t deny the claim.

“Occasionally, when I would get very upset with the rules, I would sneak out to a place where nobody would find me and, yes, pop a piece of shrimp in my mouth,” she said. But she added, “You don’t divorce your wife because she had a piece of shrimp.”

Meanwhile, Rubinger and Villaverde love maintain that it is they who have been treated unfairly — by the congregation and by the R.A., an organization representing about 1,600 Conservative rabbis.

After the rabbinical organization’s committee responsible for investigating ethics violations — the Va’ad Hakavod — scheduled an August hearing to look into complaints about Rubinger, a fierce debate erupted on Ravnet, the message board for Conservative rabbis. In one posting, Rubinger assailed the committee for denying him the right to a lawyer as well as the right to know who in his former congregation had accused him of ethical violations.

“By denying me access to who the complainants were, it effectively bars me from taking any legal action against the complainants. And by not having an attorney present, it would bar me from taking legal action against the Va’ad Hakavod itself,” Rubinger told the Forward. The rabbi added that he had resigned in order to avoid what he said would have been a “show trial.”

As a copy of the Va’ad Hakavod guidelines, provided by Rubinger, states, “The rabbi charged shall have the opportunity to read the letter of complaint and any other documents initially presented, and if desired, respond in writing.” The guidelines do not, however, call for the defending rabbi to have a lawyer present, as the committee is a nonjudicial body.

The chairman of the Va’ad Hakavod, Rabbi Harold Kravitz, said that it would be inappropriate for him to remark on any case before the committee.

While Kravitz declined to comment, the international president of the R.A., Rabbi Alvin Berkun, expressed regret over Rubinger’s circumstances. “It’s a very sad situation, and his colleagues at the R.A. are very distressed about it,” said Berkun, a pulpit rabbi in Pittsburgh. “I’ve known him for many decades and have always had a high regard for him.”

Rubinger, who also has served as rabbi at the Oceanside Jewish Center in Oceanside, N.Y., Congregation Beth-El in Massapequa, N.Y., and Congregation B’nai Israel in Vernon, Conn., said that this was probably the end of his congregational career.

“I’m not looking for a new pulpit, quite honestly,” he said.