Cooking Fried Chicken on the Upper West Side

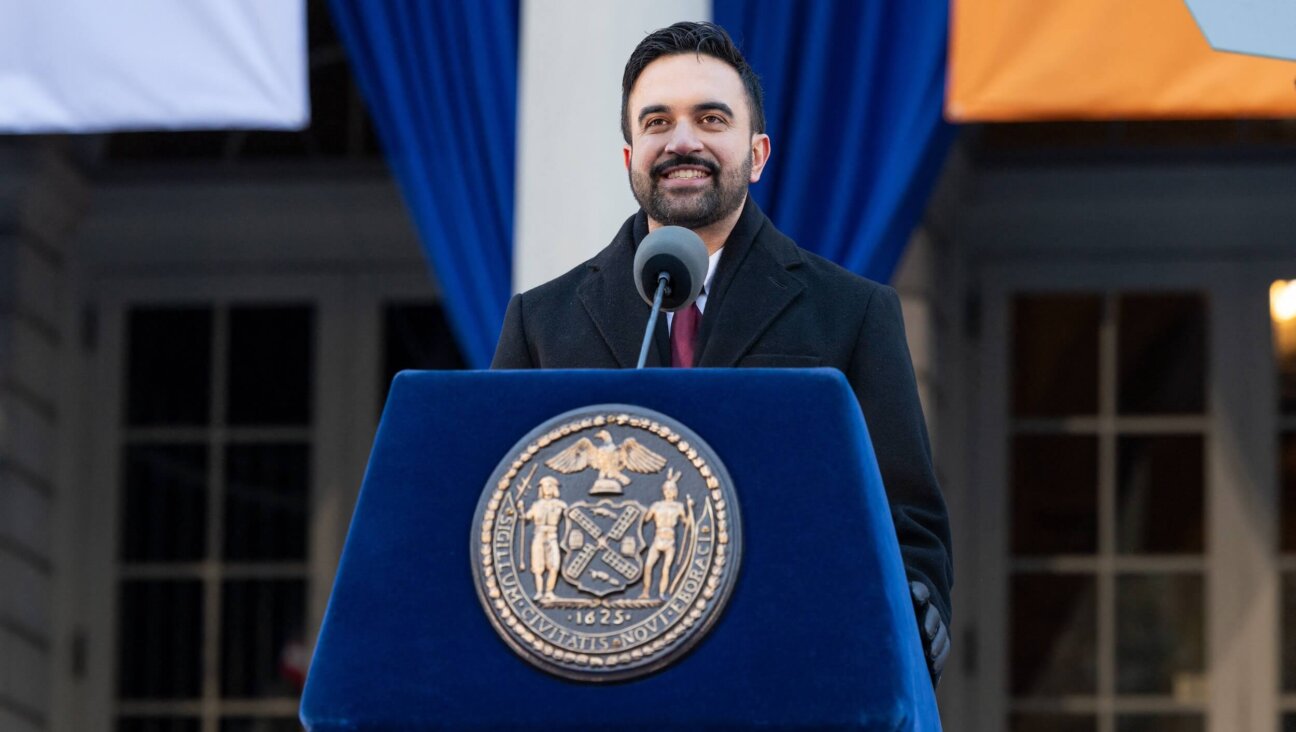

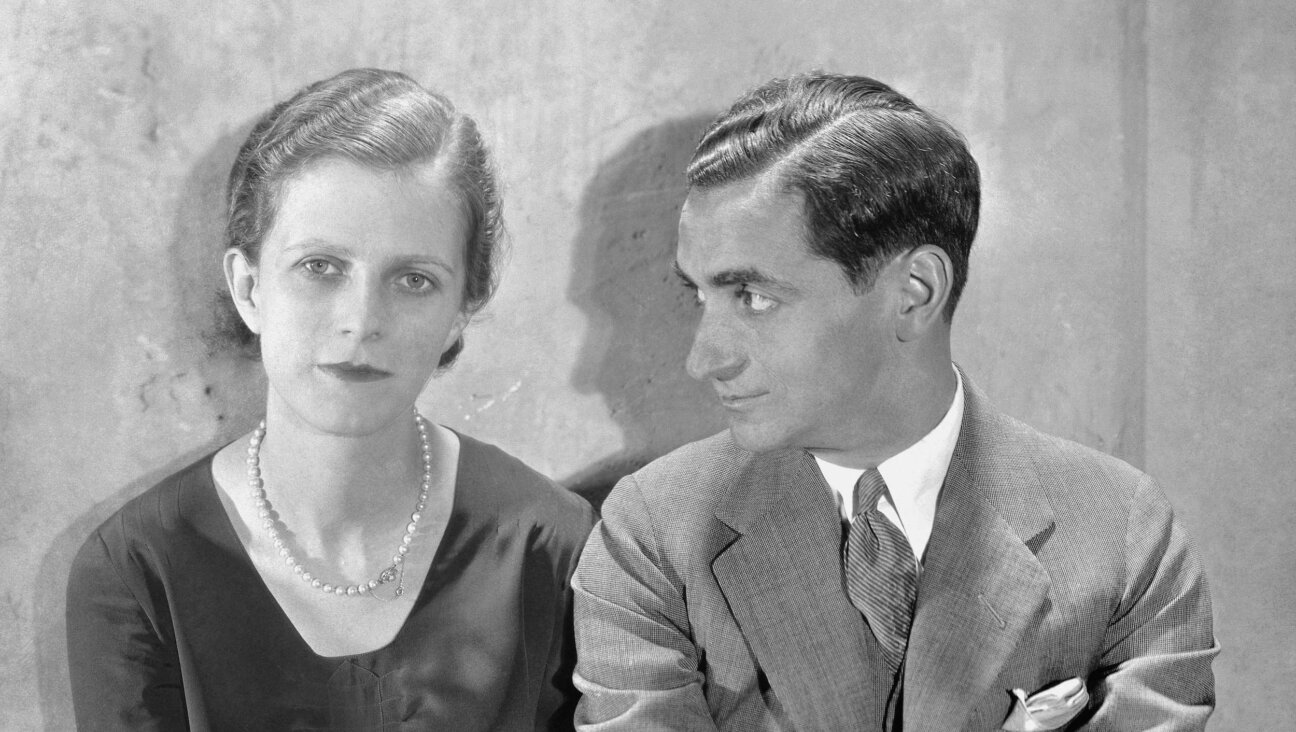

When Eli Evans’s wife, Judith, gave birth to their son, Josh, at the New York University Medical Center, Eli held a vial filled with North Carolina dirt in one hand and Judith’s hand in the other. “I did not want him to be born altogether a Yankee. I wanted him to feel some sort of call on himself,” said Evans, author of “The Provincials,” a landmark personal history about growing up Jewish in the South. “It’s hard raising a Southern kid in New York, but we’re trying.” Apparently “the dirt worked,” as the couple likes to joke. Josh, now a strapping 18-year-old, said he wants to go to college in the South.

Of the roughly 2 million Jews living in the New York metropolitan area, research yielded no statistics on how many are transplanted Southerners like Evans, a resident of the Big Apple for three decades — “It’s more than a handful. I just know that we seem [to be] everywhere,” he said — but they make up a distinct community, one that isn’t talked about much, except among one another. Interest in Southern Jewish life is growing — the documentary film “Shalom Y’all” has been making its way around the country, and the exhibition “A Portion of the People: Three Hundred Years of Southern Jewish Life” is on display through July 20 at New York’s Yeshiva University Museum at the Center for Jewish History. Yet being Southern and Jewish in New York is a complex mix of comfort and loneliness: In the South they’re the ones passing on the ribs at the barbecue; in the North they’re serving grits with the bagels at brunch.

Mort Persky, a retired newspaper and magazine editor, grew up in Aiken, S.C., where his father was the volunteer rabbi. He has lived on and off in New York for more than 40 years. “Jewish New Yorkers seem to regard being both Jewish and Southern as an oxymoron,” he said. It’s a sentiment echoed over and over by Southern Jews. Their presence in the North, in some sense their very existence, is often regarded as a novelty. Conventional wisdom dictates that sounding Jewish means sounding like a New Yorker (think Woody Allen and Mel Brooks), so sounding Southern runs in direct opposition to that.

At a party once, Persky was dragged around from group to group being asked to speak Yiddish with his Southern accent to amuse the other guests “I’m not sure I was real good sport about it,” he said, “because it wasn’t good-natured. It was mocking.”

The culture shock goes both ways. Persky remembers arriving at the New York Herald Tribune in 1962. “For the first time in my life, being Jewish was not the experience of being part of a minority,” he said, “and my whole body was totally attuned to being part of a minority.”

Even though when Southern Jews come to New York, they’re suddenly surrounded by other Jews in numbers far beyond what they could have known at home, in a sense, they’re still outsiders.

“There is a kind of existential loneliness of living in the city,” said Evans, in the lilting tones of his gentlemanly Southern drawl. “I found it very similar in an odd kind of way to being in a small town where you’re one of the few Jewish families. You’re one of the few Jewish Southerners here, and that’s a very unique identity. It’s more unique than people can imagine.”

Sixth-generation Memphis native Tova Mirvis, whose novel “The Ladies Auxiliary” is based on the Orthodox community in which she grew up, felt a sense of relief in coming to New York. In Memphis, there wasn’t a lot of room to question traditional Orthodox values, especially with regard to gender. But in New York, there are so many different schools of thought being explored within Judaism, she found being progressive and Orthodox didn’t have to be mutually exclusive. “The New York Jewish world is just so much more vibrant and has the numbers and diversity to do things that a smaller community, understandably, just couldn’t even begin to do,” she said.

Yet she still feels the tug of the South. She’s hired three baby sitters who are fellow Southern Jews, and even after 10 years of living in New York, whenever she’s traveling and someone asks where she’s from, she automatically answers, “Memphis.” Halfway through writing her latest novel (about a kosher restaurant), which she originally intended to set completely in New York, she felt compelled to work Memphis into the plot.

“Someone asked me recently how I feel about the fact that my kids won’t be Memphians. They won’t be