Peace in the Plural

Samuel Sherman from Cherry Hill, N.J., writes:

“In the traditional Hebrew and Yiddish greeting of shalom aleykhem, literally, ‘peace be upon you,’ the ‘you’ [aleykhem] is masculine plural, but the greeting is the same whether one is addressing many people or just one. And in the Catholic church there is a Latin greeting, pax vobiscum, which means exactly the same thing and also uses the plural ‘you’ even when the greeting is addressed to a single person. My questions are: 1) How and when did this Hebrew greeting originate? 2) Did the Catholic church translate the Hebrew greeting into Latin, or is it mere coincidence that the two greetings are the same?”

It is certainly no coincidence. Addressed to a congregation by the officiating priest, pax vobiscum or pax vobis, “peace be with you” or “peace unto you,” is a phrase that forms part of the Catholic Mass, which took it from the New Testament. It occurs three times there, in Chapter 20 of the gospel according to John, in the latter’s description of Jesus’ visitation to his disciples after his crucifixion and burial. The first time, John relates: “On the evening of that day, the first day of the week… Jesus came and stood among them and said to them, ‘Peace be with you.’” (“…Venit Jesus, et stetit in medio, et dixit eis: Pax vobis.”)

Since pax vobis was not a traditional Latin expression, and the Greek eirene humin, from which it was translated (the entire New Testament was originally written in Greek), was not a Greek idiom, either, both must have come from the language that Jesus spoke, which was Aramaic with a mixture of rabbinic Hebrew — and in this language, shalom aleykhem was a common form of greeting. Thus, for instance, in the Mishnaic tractate of Midot, in a description, pertaining to the time of Jesus, of how the night watchmen in the Temple were kept on their toes, we read:

“The overseer of the Temple Mount went from shift to shift with lit lanterns, and if a watchman did not stand [when he appeared], the overseer said: Peace be upon you! [Shalom alekha!] If he [the watchman] was asleep [and did not answer], the supervisor beat him with a stick.”

Note that in this passage, the overseer addresses the watchman in the singular form of alekha rather than in the plural form of aleykhem. This is similar to what we find in the Bible — where, however, shalom, peace, is never coupled with an inflected form of the preposition al, “upon,” but only with the preposition le, “to,” as when the Judean warrior Amasai says to David, in Chronicles 18:12, shalom lekha, “Peace be to you” in the singular. The pluralization of al for singular use took place later. Perhaps it developed as a polite form, the plural being occasionally used for that purpose in ancient Hebrew as it is in various European languages. (Think, for example, of French vous and German Sie, the plural forms of “you” that also came to be the polite forms of the singular.)

The proper reply to shalom aleykhem is not shalom aleykhem in return, but rather, inverting the words, aleykhem shalom or aleykhem ha-shalom. Nor, although it was once an ordinary greeting (as it still is in Hebrew’s sister language of Arabic, in which salam aleykum and the reply of aleykum as-salam constitute a simple if somewhat formal “hello”), does shalom aleykhem function as such in Yiddish or in contemporary Israeli Hebrew. In both these languages, it is an emphatic hello that is generally reserved for someone with whom one has not met for a long time, or whom one is surprised to have encountered. This is probably the reason that Yiddish writer Sholem Rabinowitz chose it as his pen. The writer appeared widely but irregularly in the Yiddish press of his day, so that, before it simply became his name, his pseudonym of Sholom Aleichem was a way of saying to his readers, “Hello, there, I’m back again!”

To return to the Catholic Mass — in its singular form of pax tecum, the phrase “peace be unto you” was also the salutation used after the so-called “kiss of peace,” a custom observed in the early and medieval church in which members of the congregation kissed one another during the Communion ceremony. The “kiss of peace” was eventually abandoned in Catholic practice because not all the kissing — or so it seemed to the church authorities — was done in a purely spiritual state of mind, some congregants taking advantage of it to express other emotions. In late medieval times, kissing one’s fellow worshippers was replaced by kissing a “pax board,” a plaque of metal, ivory or wood, carved with some sacred theme, that was passed from congregant to congregant. Yet eventually, this, too, was dropped from church ritual. Today, pax tecum, accompanied by a symbolic kiss in the form of almost but not quite touching cheeks, is uttered in the Catholic Mass only by one member of the presiding clergy to another.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected].

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

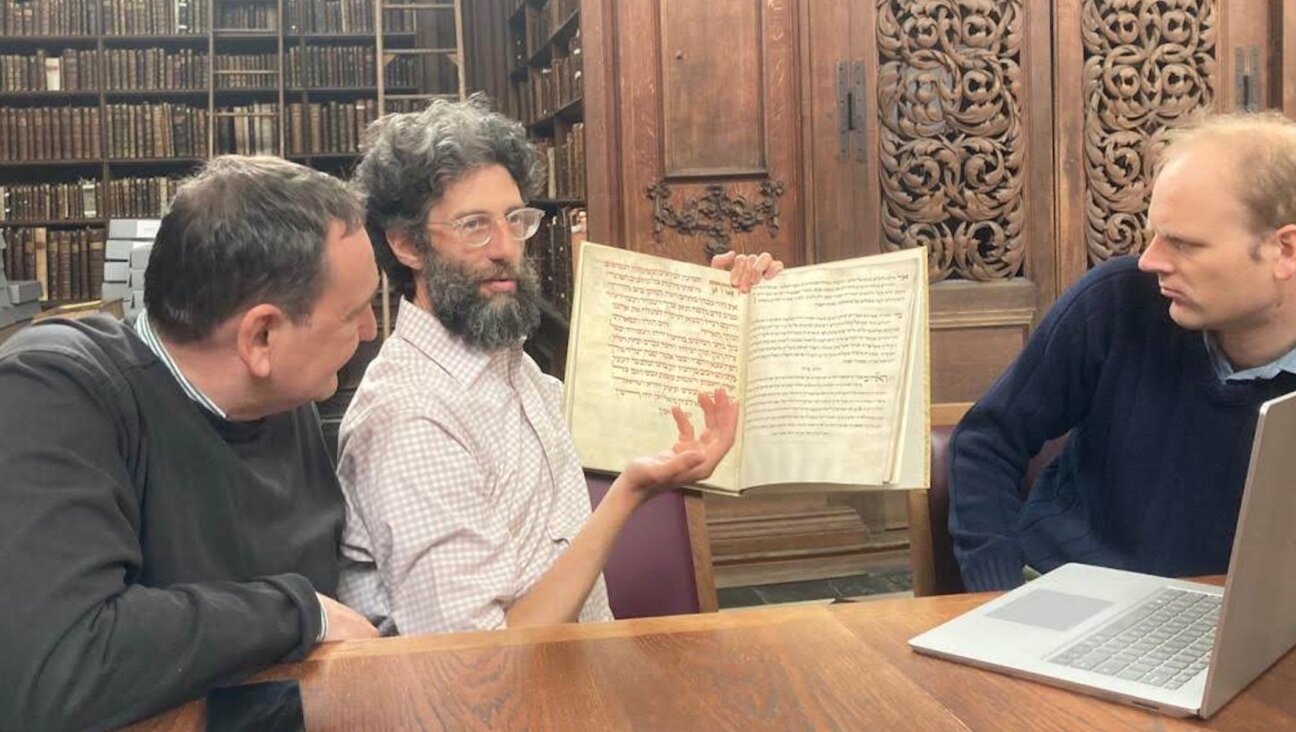

Fast Forward For the first time since Henry VIII created the role, a Jew will helm Hebrew studies at Cambridge

-

Fast Forward Argentine Supreme Court discovers over 80 boxes of forgotten Nazi documents

-

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.